Consumer-packaged-goods (CPG) companies in Southeast Asia might one day look at today’s market as the lull before the storm. While online purchases of physical goods have been slow to catch on in the region, new technologies, competition among sector leaders, and changes in consumer expectations are likely to accelerate the process. Incumbent CPG companies should prepare for this inevitable shift, taking the opportunity to safeguard their revenues and profits and adjust their business models to align with the new reality.

The stakes are high

The value at risk for CPG companies is consequential. Globally, comparing the periods 2001–05 and 2011–15, McKinsey found that consumer-sector losses in economic profit, measured by return on invested capital, ranged from 7 percent in the food sector to 18 percent in household products and beverages (Exhibit 1). When comparing these periods, economic profit dropped between 20 and 40 percent in some industries in Europe and North America, despite efforts like zero-based budgeting. The fall in absolute economic profit only partially reflected the decline, as invested capital had simultaneously increased.

Digital has driven much of the loss in these markets by enabling the rise of small brands, accelerating channel shift, and facilitating ever-increasing demand from consumers. It did not have to be this way, however. Digital has just as much potential for value creation. Indeed, while large CPG companies in these markets have lost value, nimble disruptors (for example, Beyond Meat, the Honest Company, and innocent) have created billions of dollars of economic value by using digital to grow their businesses. We see latent potential in Southeast Asia. While some of these trends (such as the penetration of e-commerce and the impact of global giants, such as Alibaba and Amazon) have been less pronounced in Southeast Asia, others (including growth of the millennial demographics, greater demand for convenience, and generally increased digital savviness) are quite noticeable.

Domestic companies in Southeast Asia and multinationals with operations in the region will both have to prepare to face the full breadth of these market changes (Exhibit 2). Otherwise, our analysis suggests, CPG companies in the region could lose up to a fifth of their value.

Digital technologies transforming Southeast Asia

To date, online sales of physical goods have played only a marginal role in Southeast Asia. But the impact of digital technologies is starting to transform the region, with e-commerce near a tipping point; digital-savvy consumers; the battle of global companies, local leaders, and unicorns; and the pervasive position that technology is taking across the value chain.

E-commerce close to tipping point

Online retailers have captured a 21 percent market share in China outside of grocery. However, their presence has barely been felt in Southeast Asia, charting market shares of just 2 percent in Thailand and Vietnam, 3 percent in Malaysia, and 6 percent in Singapore (Exhibit 3).

This lull could end quickly, however, catching many incumbents by surprise. Digital-payment technologies, improved logistics infrastructure, and regulatory shifts, for instance, are creating favorable conditions for online retailers. Online sales have already disrupted some categories in Southeast Asia. For example, in Vietnam, about 15 percent of consumer-electronics sales occurred online in 2019. Experience in China and the United States has shown that once supply and demand coincide, online sales can accelerate quickly.

Digital-savvy consumers

Even though Southeast Asian consumers have been slow to embrace online shopping, they are very active digitally. For example, mobile and smartphone penetration is 76 percent in Malaysia and 80 percent in Vietnam. One result of this digital prowess is that online research influences many purchase decisions in the region.

As well as researching product quality, digital-savvy consumers, bombarded by online promotions, can compare offers by measures such as choice, price, and many other factors. Together, this adds pressure on CPG companies to improve the value of their goods and to work harder to retain customer loyalty.

The battle among global giants, local leaders, and unicorns

At the moment, Lazada and Shopee are the only truly regional online marketplaces, and domestic markets remain very fragmented (Exhibit 4). Yet we expect domestic markets will consolidate over time, becoming dominated by two or three powerful ecosystems. The battle will feature multiple contestants. Local leaders, such as Charoen Pokphand in Thailand, and the Salim Group in Indonesia, and Vingroup in Vietnam, have invested aggressively in digital technologies. Regional unicorns, such as Gojek in Indonesia and Sea in Singapore, are expanding throughout the region. Global giants, including Alibaba, Amazon, JD.com, and Tencent, are testing the waters.

In addition, digital super wholesalers—for instance, Bukalapak of Indonesia—mimic Alibaba’s Ling Shou Tong in consolidating B2B purchases through a limited set of apps. The growth of these intermediaries presents CPG companies with another powerful stakeholder in the value chain.

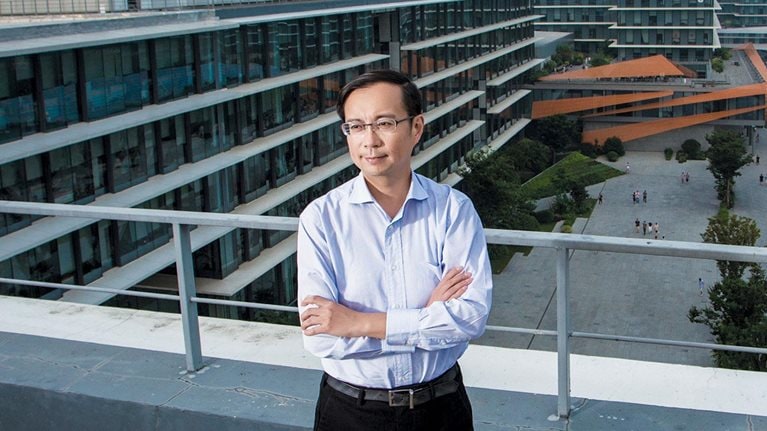

In this complex landscape, while the ultimate winners remain unclear, consolidation and the rise of ecosystems appear inevitable. Alibaba CEO Daniel Zhang, for instance, has declared Thailand a priority for its first conquest outside China, and other corporate leaders have made similar pronouncements.

Also, substantial funds have been flowing into Southeast Asia’s digital economy. Between 2015 and 2018, capital raised by digital ventures increased more than tenfold. Altogether, $24 billion was invested in digital efforts in the region during that period, primarily in ride-sharing and e-commerce platforms. Indeed, Chinese giants Alibaba and Tencent, among others, have entered most Southeast Asian markets and backed local champions, as a rapid consolidation occurs around a handful of core companies (Exhibits 4 and 5).

The CPG companies that come out on top in this contest will be those that follow the consumer onto every channel and address needs that are changing rapidly.

Rapid technology adoption

New digital technologies will reshape every industry globally, and CPG will not be different. The combination of digital-savvy consumers, the penetration of smartphones, and the commitment of digital giants and unicorns makes us believe that e-commerce will leapfrog more advanced countries. Three factors combine to hasten the CPG transformation:

- Data. CPG companies and retailers collect an unprecedented amount of data, including information drawn from transactions, that can help create nuanced consumer profiles. In one aspect, these data can create “segments of one”—detailed knowledge of individual shoppers that provides clear competitive advantages.

- Computing power. Stronger, cheaper computing power allows companies to analyze data at new depths and generate unprecedented insights. With this power, for instance, companies can model and predict consumer demand for very small segments, informing decisions in areas such as innovation and pricing.

- Consumer intimacy. CPG companies can now communicate directly with consumers over multiple channels, engaging in two-way conversations that can influence purchasing decisions and augment traditional marketing.

These tectonic shifts present an unparalleled opportunity for CPG companies. The changes not only can open access to hundreds of millions of consumers across Southeast Asia but also can be the source of critical competitive advantage. The global companies that can draw the most valuable insights from the data, create robust distribution networks that use new technology, innovate faster, and cater to local tastes, among other efforts, will create a clear edge in the market.

Disrupt or be disrupted

Amid the pressures related to digital technology and the likely growth of online retailing, CPG companies active in Southeast Asia must begin preparing now—if they haven’t begun already—for the inevitable market changes. Our research and experience, both globally and within the region, suggest four crucial requirements for maintaining and creating value in this environment.

Would you like to learn more about our Consumer Packaged Goods Practice?

Play offense, not defense

Online retailing is still in the early stages in Southeast Asia, and sufficient room remains for CPG companies to be selective in their business models and in choosing partners. Traditional sales channels remain dominant in the region and account for most of the industry’s sales and profit. Because any transition to a digital economy is likely to weaken these traditional channels, CPG companies must choose carefully where to compete and where to invest.

The online channels and ecosystems being built in the region vary widely by market and industry. CPG companies must understand the differences and clearly identify their strategic goals when engaging in online commerce—for instance, to drive sales, enter new markets, or buttress their brand, among many other options.

Companies will have to choose among several models—their own online presence, an open platform, or an established ecosystem, for instance—to bring their goods to the digital marketplace and to choose among all the various paths emerging between online activities and offline purchases. Companies must also identify which online customers to target, which capabilities to build internally or outsource, and their own specific aspirations. They must play offense—putting a stake in the ground by choosing a partner early or launching efforts to go direct to consumer (D2C). Examples in cosmetics have already shown fully D2C new entrants, such as Dr.Jill in Thailand and Ertos in Indonesia, disrupting the industry. However, those D2C models only work under a specific set of conditions.

Accelerate innovation and build resilient models

In the digital economy, category management becomes more complicated. Conflicts across channels are likely to arise. As a first step, CPG companies must clearly segment the assortment available over traditional channels, via modern trade, and online and set appropriate prices and promotional guidelines for each.

With channels blurred—few, if any, consumers would restrict themselves to a single channel—conflicts will arise. Companies should handle them using distinct execution rules for each segment. Of course, companies should make an effort to avoid these conflicts as much as possible—in many cases, through common sense—but it will no longer be sufficient to understand, say, price elasticities within a specific category.

In addition, CPG companies must understand the new constellations of product substitutes and cross-channel price sensitivities, all on a granular, regional level. Their speed of innovation needs to match the blurring channels and the rise of small brands, creating distinct purchase opportunities and brands that follow consumers wherever and whenever they go.

Disrupt the value chain preemptively

Ecosystems are not just delivering better consumer experiences. They are also taking billions of dollars in costs out of processes by digitizing distribution and removing traditional intermediaries. For example, Ling Shou Tong in China links traditional stores to an online resupply platform, owning the relationship and customer data, bypassing the multiple layers of wholesalers typical of traditional trade, bringing efficiency to the system, and generating greater value as the business grows. This shift can transfer entire value pools from value-chain intermediaries to ecosystems, redistributing access to consumer data and the power to monetize the data.

To counter disruptions triggered externally, CPG companies must be proactive in orchestrating their own disruptions. Undoubtedly, they must remove inefficiencies in their own value chains before someone else does. Reviewing their core businesses and using digital technologies and advanced analytics are critical steps toward this goal. The threat from competing ecosystems can only manifest if these ecosystems truly create greater efficiencies than those delivered by legacy CPG manufacturers.

CPG companies can also lead the change by creating tech-driven consortia with other companies to manage their own distribution and avoid losing touch with the outlets and customers—and the data these relationships provide. In our experience, many CPG companies think about the fragmented trade and point-of-sale systems. Few have a grand picture of their own inefficiencies or understand how attackers could exploit those inefficiencies in their quest for better value and service for the consumer.

How consumer-goods companies can win in Southeast Asia

Escape ‘pilot purgatory’

A quip in the industry is that “CPG companies have more pilots than Lufthansa,” the German airline. Millions of dollars have been spent in the industry on digital initiatives that fail to pay off, often because they are never pushed beyond the pilot stage.

Instead, companies must break the inertia and bring promising initiatives to scale quickly, escaping “pilot purgatory.” Experimentation remains essential, of course. Beyond launching new online offerings, experimentation can create a new, agile approach to innovation that explores many avenues (such as new distribution networks based on digital wholesalers or D2C deliveries) quickly.

But these efforts will bring one-off benefits, at best, unless the most promising are expanded quickly. For example, once it is clear how a company can use nascent ecosystems to further its interests, senior leaders should be ready to invest as needed to bring the initiative to scale. In some cases, this will mean relying on emerging B2B platforms and aggregators to complement or replace traditional market channels—or even launching an entirely new business. In other cases, it will mean focusing on the three to five use cases with the greatest potential across functions in priority markets. Country managers of multinational companies will not take digital efforts seriously unless they improve the bottom line, and that requires scaled efforts.

In almost every case, though, bringing promising initiatives to scale will require identifying the correct partners, with complementary capabilities and infrastructure. Emergent digital capabilities, whether in modern logistics or advanced data analysis, are crucial to success, and companies will usually have to complement in-house skills with those offered by trusted partners.

Weak online sales to date in Southeast Asia may lull CPG companies into complacency. Those with vision, however, will not be fooled: they will prepare early for inevitable market changes. They will take multiple initiatives, from enhancing category management to embracing digital technologies, to ensure that they can ride out—and even benefit from—the coming disruptions. With annual economic growth in the region continuing at around 5 percent, companies that get it right will prosper by riding the growth wave and cutting costs to unlock even greater profitability. And as fears of a global economic slowdown loom, the urgency for action only increases. Efforts now could easily define those who survive the disruptions and emerge as leaders.