With each passing day, established companies encounter valuable opportunities to grow and innovate—along with intense competition, which has made it harder than ever to stay on top. The companies listed on the S&P 500 index have an average age of 22 years, down from 61 years in 1958. One factor that sets winners apart is their ability to build successful new businesses repeatedly. According to our research, six of the world’s ten largest companies might be called serial business builders, having launched at least five new businesses during the past 20 years, and two more of the ten have built sizable new businesses.

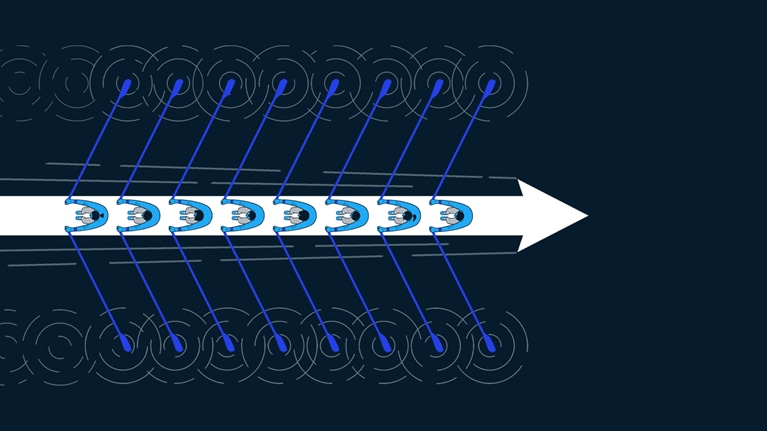

This isn’t a coincidence. Established companies possess talent, funds, market insights, intellectual property, data, and other assets that can give their new businesses a decisive edge over stand-alone start-ups. Providing access to an existing customer base, for example, can lower the cost of acquiring customers and speed their uptake, thereby putting the new business on a faster growth trajectory. When established companies develop the ability to integrate their assets with tech-enabled business models, they can continually generate new businesses.

Doing so well requires four elements: strong CEO sponsorship, carefully structured relationships between the parent company and its ventures, the discipline to fund new businesses as they test and validate their ideas, and a skillful business-building team. In this article—based on our experience in leading more than 200 business builds in a range of sectors, including banking, insurance, oil and gas, retail, and telecommunications—we offer a look at how an incumbent can learn to build businesses that combine its strengths with a start-up’s flexibility and pace.

Creating a business-building capability

Business building is no longer a choice: it is an essential discipline that lets incumbents counter disruptive challengers and sustain organic growth. New businesses can also serve as proving grounds for agile and design thinking, so an incumbent’s executives can gain exposure to these practices before introducing them to core businesses. But for many incumbent companies, building new businesses—especially those with a business model substantially different from the parent organization’s—will be an unfamiliar endeavor. In our experience, large companies develop their business-building capabilities most effectively by emphasizing four activities.

1. Voicing the business-building imperative: The crucial influence of the CEO

Many executives at long-standing companies have told us that building new businesses feels altogether unnatural and risky. They doubt that their organizations can progress beyond traditional operating models and ways of thinking. And the high failure rate for start-ups suggests to many executives that they would be wiser to seek less risky, more familiar places to invest in pursuit of growth.

Faced with arguments against building new businesses, CEOs at established companies must advocate strongly for business building. They bear the responsibility for articulating and reinforcing the need to create businesses that reach new customers in new ways and achieve high-margin growth. Investors constitute the most important audience for such messages. CEOs must convince them that the companies’ investments in new businesses will yield better returns than investments in alternative growth opportunities.

To make an effective case for business building, CEOs should be up front about new businesses’ capital requirements (which can approach or exceed $100 million per business) and time frames for achieving profitability (usually three to five years). As McKinsey research has shown, organic growth typically generates more value than acquisitions do but takes longer to lift revenues and profits. For that reason, a CEO will normally find it helpful to update investors regularly on how the company’s business-building efforts are progressing and to remind them that such efforts take time to pay off. Internal stakeholders matter, too. To ensure that new businesses gain advantages from the parent company’s assets, the CEO must keep business-unit and functional heads informed and involved.

For example, we know of one CEO who concluded that, to grow, his company should enter the burgeoning market for Internet of Things (IoT) products. He recognized that his company lacked the capacity to develop IoT products, so he resolved to build new businesses that could innovate quickly. The CEO made clear to business-unit and functional leaders that they should treat the business-building effort as a high priority. When the company launched the first of these IoT ventures, the CEO empowered its leadership team to call on executives in the core business for help—and promised to intervene if any executives were slow to accommodate the requests of the team. Backed by the CEO, the team quickly delivered a minimum viable product (MVP).

Would you like to learn more about McKinsey Digital?

2. Powering up new businesses: Ample assets, minimal encumbrances

Unlike stand-alone ventures, new businesses built by incumbents can gain decisive advantages from the parent company’s funding, customers, data, intellectual property, technology, and other assets. One bank, for example, allows its new businesses to market their offerings to existing bank customers with the assistance of the bank’s frontline staff, thereby helping the new businesses gain traction. To maximize these advantages, large companies should allow their new businesses to determine which of their parent companies’ assets will provide the greatest benefits to the new ventures and to draw on those assets with few, if any, conditions.

Creating this kind of relationship between a parent company and a new business can involve a delicate balancing act. Once employees from the parent company start supporting a new business, they often try to hold it to the larger organization’s standard processes and ways of working. But these conventions can be antithetical to the working styles of new businesses, and even stifle their activities. In our experience, bureaucratic interference and insufficient use of the parent company’s assets are common reasons why the business-building efforts of large companies may come up short.

Because of this, executives should avoid treating new businesses as parts of the legacy one. It’s more effective to buffer them from the parent company’s processes and requirements. One way incumbents do so is by setting up new businesses as self-contained, relatively autonomous entities, with their own leadership teams, governance mechanisms, management practices, and talent environments (including career paths and rewards). Another is by untethering new businesses from the parent company’s planning and budgeting cycles. Rather than requiring new businesses to compete with core divisions for funding, incumbents can earmark capital to invest in new businesses and release allotments of money when they reach agreed-upon development targets, as we discuss below.

BP, the global energy company, followed this approach when it set up Launchpad, a “factory” that takes technological innovations created by BP’s R&D department and builds new businesses that commercialize those innovations at scale. Working from Launchpad’s separate office, the new businesses tap into the assets of BP by working with designated representatives of its functions, who use their relationships within the company to help its new businesses gain advantages (such as access to customers) from its scale.

3. Building to the limits of what’s proved: How testing helps manage risk

Promising ideas don’t always make for good businesses, as any seasoned venture investor will tell you. Yet an incumbent company or a new business’s founding team can easily but wrongly convince itself that a business idea could succeed and then pour money into it. Venture investors counter the optimism of founders by challenging them to demonstrate that their ideas are viable. Similarly, incumbent companies should insist that the leaders of a new business unpack their assumptions about the business’s prospects, identify the risks it will face, and validate their plans for managing those risks. That way, the company can fund continued development of the business only to the extent it has been validated.1

In our experience, founding teams often make significant assumptions about factors that will determine the revenues of the new business, such as the number of customers they expect to win, which is partly a function of the conversion rates a team expects to achieve at each stage of the sales process. Other crucial assumptions pertain to operating expenses, such as how much it will cost to acquire customers.

To test such assumptions, venture leaders often find it helpful to forecast “reverse” profit-and-loss statements (so called because executives forecast the profits of the business and work backward through its costs to its revenues) for the next five years. Then leaders tease out the assumptions behind each line of the statements, determine what risks might prevent these assumptions from coming true, and test the plans for addressing those risks. This process should compel the leaders either to confirm that their assumptions are sound or to adjust them to reflect the business environment better.

An example of how the test-and-learn approach helps dismantle faulty strategic assumptions comes from a large industrial-products company, which had formed a venture to create an open software platform supporting connected products in business settings. The executives leading the new venture expected installers of such products to see the software platform as a threat. Although these executives were confident in their outlook, they were also committed to validating their assumptions by talking with installers and other parties whose business would be affected by the platform. To the executives’ surprise, the installers said they felt the platform would benefit them. They went on to advise the venture about features that customers would value, and some signed on as partners when the platform came to market.

New businesses also control product-related risks by showing their offerings to potential customers at an early stage, collecting feedback, changing the offerings accordingly, and continuing to test and tweak products often. This approach helps new businesses validate the features and other attributes they’ve selected and quickly create an MVP that many customers will pay for. Established companies also test new products, of course, but few do so as early and often as start-ups. A corporate venture we know tested product mock-ups with customers just six days after a product was conceived—a major departure from the parent company’s practice of testing prototypes after six months or more of development.

The innovation commitment

4. Sustaining momentum: Creating a business-building team

It’s one thing for an established company to sponsor relatively low-risk growth efforts, such as extending product lines or introducing products to new markets. Building new businesses—which is riskier but more rewarding—calls for a different approach, supported by different organizational structures. In particular, repeatedly building new businesses requires a team dedicated to evaluating business ideas, choosing which ones to support, securing leaders for the new businesses, and overseeing their development. These responsibilities include making sure that the founders of new ventures test their assumptions (as described above) and discontinuing ventures that are exposed to unmanageable risks.

The strongest business-building teams we’ve seen include entrepreneurs hired from outside the parent company, who bring valuable experience in leading and building start-ups; executives from the parent company, who help new businesses gain advantages from the parent company’s assets; and a pool of specialists in design thinking, software development, and other business-building disciplines, who lend their expertise until new businesses are large enough to bring in their own specialists. Successful incumbents also endow their business-building teams with enough authority to scale up new businesses as they see fit, provided that they validate their assumptions and honor the parent company’s strategic objectives.

At the industrial-products company mentioned above, executives chose to bring in a new leadership team for the connected-product-platform business when they realized that the several dozen software engineers developing the software platform lacked direction and organizational support. Senior management assembled a team of seasoned entrepreneurs, recruited externally, and executives from related divisions of the industrial company (such as finance, operations, and IT), selected for their ability to foster collaboration between the new business and its parent. By carving the business out as a separate legal entity, the industrial company gave the new leadership team more flexibility, which allowed it to define the new business’s market in a way the company hadn’t thought about, to sharpen the product concept, and to accelerate product development.

How to begin your business-building transformation

Companies cannot afford to delay building new businesses: opportunities to achieve breakthrough growth are too precious to pass up, and the pressure to defeat innovative competitors is mounting. CEOs and senior executives can initiate their business-building efforts by exploring the following issues:

- Aspirations and opportunities. To draw up a portfolio of new businesses, executives must decide where they want to take their company and how business building can help it advance in that direction. Several questions can help focus the executives’ thinking. What should our company look like in five to ten years? What organic-growth opportunities must we exploit to achieve our targets? Which new business ideas would let us seize those opportunities? Why haven’t we pursued those ideas yet? Which of our assets could give new businesses a greater chance of succeeding?

- Experience and environment. Generating meaningful growth by building businesses requires more than a single push; it calls for a lasting effort. Management teams should ask themselves a few hard questions. Do we have enough knowledge and talent to sustain such an effort and whatever more we need to develop a business-building capability? What have we learned from our previous and ongoing efforts to grow organically? What allowed us to succeed, and what kept us from succeeding? Who are our most creative, entrepreneurial executives and managers? Which of them have displayed an eagerness to work on big, ambitious growth projects?

- Resources. No matter what parent-company assets might be available, new businesses can’t start without two basic ingredients: funding and people. Executives must decide how much capital they can set aside for business building. For companies in mature or shrinking markets with few growth opportunities, the amount might be large. For those in growing markets, it might be smaller. As for staffing, our experience has taught us that strong business-building teams count for more than business ideas. A strong team will kill a bad idea quickly and turn a great idea into a successful business, whereas a mediocre team will squander time and money on bad ideas and fail to commercialize good ones. Executives should ask themselves if they know where and how to recruit supporting talent (such as data scientists, designers, developers, and ecosystem architects) and whether they can provide such employees with incentives and career paths that support testing and learning and tolerate failures.

It’s increasingly clear that established companies that haven’t developed the ability to start scalable new businesses repeatedly are at risk of falling behind their competitors. Business building is no longer an optional way to generate organic growth: it has become essential. Fortunately, incumbents can use their assets to give new businesses advantages over independent ventures. Executives who combine those assets with advanced technologies and a start-up’s culture and ways of working can create a business-building capability that powers continual organic growth.