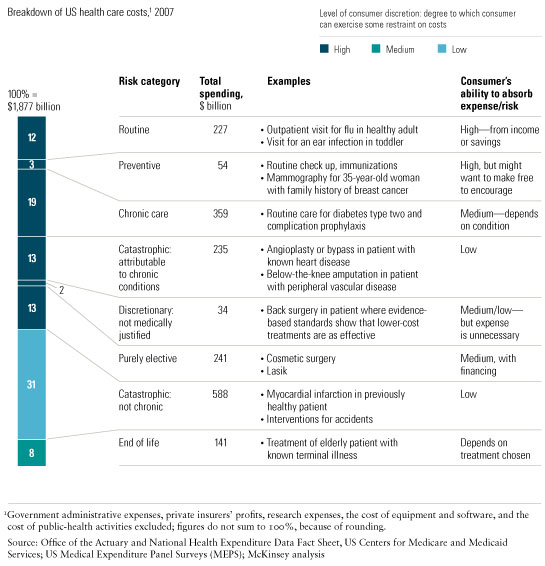

The fundamental nature of medical risk in the United States has changed over the past 20 to 30 years—shifting away from random, infrequent, and catastrophic events driven by accidents, genetic predisposition, or contagious disease and toward behavior- and lifestyle-induced chronic conditions. Treating them, and the serious medical events they commonly induce, now costs more than treating the more random, catastrophic events that health insurance was originally designed to cover (Exhibit 1). What’s more, the number of people afflicted by chronic conditions continues to grow at an alarming rate.1

As the nature of risk has evolved, neither the funding mechanisms nor the forms of reimbursement for health care have adapted adequately, so the system’s supply and demand sides are both hugely distorted. Consumers are overinsured against some risks and underinsured against others; woefully short of the savings required to pay predictable, controllable expenses; and all too likely to be dealing with doctors who have big incentives to treat individual episodes of care rather than prevent illness and manage chronic conditions effectively.

The nature of health care risk

These are important—yet frequently overlooked—points in the current debate about the future of health care in the United States. With the US government poised to spend billions of dollars to support universal access, reformers must understand this shift in the nature of risk and move to align financing mechanisms and reimbursement with it. Pouring more money into the system without modernizing it will probably worsen the health care challenges facing the country.

Legislation and action by the government or private insurers should offer consumers a chance to buy enough protection to feel financially secure but also require them to share in the cost of care and give them incentives to manage risks under their personal control in a value-conscious way. Just as important, the United States needs to have the reimbursement and care delivery models that best control each type of risk (see sidebar “What the future may hold”).

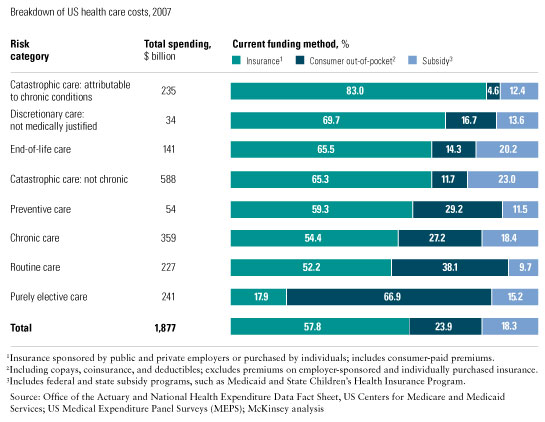

To better inform the debate on the health care system, we offer a new way to look at the distribution of costs within it. We break down the country’s health care spending into separate risk categories, map them to specific medical conditions by their unique characteristics, and identify who pays for what (see sidebar “About the research”).

Misalignment with risks

Because insurance is the dominant financing mechanism and fee-for-service is the primary way of reimbursing providers, the US health care system is misaligned in two respects. First, consumers are overinsured for some risks and underinsured for others, so the system doesn’t offer incentives for healthy behavior, promote value-conscious consumption, or provide adequate financial security. Second, in a fee-for-service world, providers have a financial incentive to undertake as many procedures as possible—a model especially ill-equipped to manage increasingly prevalent chronic conditions.

This misalignment is a relatively recent phenomenon. Insurance is effective if it pools random, infrequent, and unpredictable risks. When health insurance was introduced, in the 1930s, it did precisely this. Over the decades, however, it expanded to cover an increasing array of services, largely because employers wanted to attract workers by providing a tax-advantaged benefit. In the 1980s and early ’90s, managed care promoted this trend by offering consumers “first-dollar coverage,” reimbursing routine services and expenses for treating conditions that weren’t random, infrequent, and catastrophic in exchange for the patients’ willingness to cede decision rights on treatment choices to primary-care physicians. When managed care lost popularity, consumers regained choice but largely retained first-dollar coverage.

The more recent shift requiring consumers to share more of the cost sought to correct this imbalance through products such as high-deductible health plans combined with health savings accounts. Some of the cost shifting, though, wasn’t sufficiently nuanced and left many consumers underinsured and financially exposed in certain risk categories. Requiring consumers to bear 11 percent of the cost of treating a catastrophic event, for example, exposes many people to financial hardships, since it may cost tens of thousands of dollars. The current approach also does little to promote value-conscious consumption—after all, people have only a limited ability to avoid accidents and can hardly shop for medical care when they happen (Exhibit 2). Furthermore, the fact that consumers cover almost 30 percent of the cost of preventive care conflicts with the goal of maximizing its use.

Misaligned funding

As we have seen, the system also suffers from misaligned supply-side incentives, given the predominance of fee-for-service reimbursements to providers. Prices are set through long-term contracts between them and government agencies or private insurers, so their primary financial incentive is to increase the volume of profitable services, such as imaging. Current incentives, moreover, fail to encourage the desired outcomes across categories of risk; for example, insurers are mainly responsible for financing delivery risk—the cost and quality outcomes of care. This approach leads to the overuse of health care services, since consumers have little incentive to curtail their use of the system, while providers have a strong incentive to increase their volume of services.

These issues are particularly vexing for chronic conditions because the fee-for service reimbursement model is fundamentally misaligned with the need to manage long-term health outcomes. That kind of management is essential to reduce the incidence of expensive catastrophic events arising from the complications of chronic diseases (amputations, for example, as a result of unmanaged diabetes), but the reimbursement system does little to encourage it. In fact, under the current system, with few exceptions, providers earn more revenue when catastrophic events occur. More troubling still, the fee-for-service model tends to fragment the provision of care into scores of unrelated interventions. Yet the effective management of chronic disease calls for integrated, coordinated care among many different types of physicians and between them and medical institutions.

Seeking proper alignment

The underlying goal of reform should be to align risks—both risk exposure (lifestyle choices inducing chronic conditions) and expenses incurred (treatment choices affecting costs and outcomes)—with the parties best equipped to control them. To achieve this goal, it will be necessary to determine the most appropriate financing mechanisms and provider-reimbursement models for each health care risk category; one-size-fits-all approaches are counterproductive in an increasingly complex health care world. For some risks, it will be appropriate to use sophisticated reimbursement methods: bundled payments for episodes of care, capitation (a fixed payment per year per member), or risk-sharing arrangements. In many cases, however, relatively simple fee-for-service payments will remain the model of choice.

Routine expenses

Most US households can afford relatively frequent fee-for-service medical episodes such as a visit to a physician to treat a fever or to a pediatrician to treat a toddler’s ear infection. The most efficient way to pay for such services is not insurance but rather savings in the form of cash, checks, debit cards, or credit cards. (The indigent ought to receive subsidies.) The reimbursement model for these services should resemble that of any other consumer service—providers make value-based sales to consumers who pay them directly. As in the case of other services, each consumer segment will value features such as convenience, speed, and quality differently, so providers have opportunities to differentiate themselves. One such innovation, consumer-oriented retail clinics, provides a clear value proposition by offering convenient locations, limited waiting times, and transparent, fixed, and relatively low prices.

Preventive care

There is also little financial need for insurance to cover preventive-care services, such as vaccinations and screenings (like mammograms) to detect high-risk conditions early, since they too offer substantial benefits at relatively affordable prices. These services, however, are essential to maintain the medical health of society and to control the cost of treating illnesses in the future. As a matter of good public policy, this type of care should therefore be available as widely as possible, at little or no charge, to ensure the greatest possible access.

General public-health spending by the government could finance such services, or they could be a required part of the coverage of every health insurance product. Fee-for-service reimbursement is simple and effective here.

Chronic care

The largest, fastest-growing health care risks are chronic conditions and catastrophic events attributable to them, such as angioplasty or bypass operations for heart disease and below-the-knee amputations for peripheral vascular disease. Addressing this type of medical risk arguably requires the biggest changes in the current system. New financing mechanisms are needed to manage such conditions cost-effectively over long periods of time by financing investments in wellness and care management today so that costs fall tomorrow. These mechanisms must give consumers incentives based on behavioral-economic principles that promote healthy behavior and value-conscious consumption of care. Finally, it will be important to give the providers incentives compatible with the need to manage health outcomes across the whole population of chronic patients and to provide multidisciplinary, coordinated care throughout the delivery system.

Devise longer-duration, portable financing mechanisms. Once you have a chronic condition, the cost of managing it is fairly predictable—this isn’t an insurable expense, which ought to be random, infrequent, and unpredictable. Further, in effective treatments for chronic conditions, true value accrues over time by precluding their progression and, especially, the catastrophic events related to them.

To encourage investments in wellness, prevention, and disease management, health insurers or integrated health care providers must embrace long-term “ownership” of the patient—something akin to life insurance, which offers coverage that often stretches over many years or even an entire lifetime. Three broad types of financing mechanisms could be effective: multiyear term policies, annuities (pay a lump sum today for a contract covering chronic-care expenses permanently or for a fixed period), or self-insurance (pay out of savings or income).

One example of a multiyear term policy is a product, providing five-year coverage for diabetics, introduced by the Indian life and health insurer ICICI Prudential. The premiums of those who manage the condition effectively (for example, blood sugar levels and weight) are reduced by up to 30 percent. This product also provides additional incentives, as well as preventive-care and wellness services, including free checkups and home collection of blood samples for testing.

Since the consumer controls much of this risk through behavioral choices, the financing mechanisms should include incentives to address the emotional and behavioral biases that stand in the way of rational lifestyle and health care choices. Just shifting costs is ineffective, since it often fails to differentiate between unnecessary and sensible (preventive services) utilization. But rewards and penalties based on insights from behavioral economics and other behavioral sciences can work well.2

Design reimbursements tied to long-term health management. Reimbursements to providers should be based on long-term health-management outcomes rather than the fee-for-service model. A sensible system could involve capitation or risk sharing, with outcome-oriented payments reflecting how well a provider manages a condition. The effective management of chronic disease and multiple disorders often requires collaboration among specialists from many medical disciplines, so the reimbursement structure should reinforce coordination of care. Experiments with patient-centered medical homes—a form of integrated care management—may well show how to manage the risks of chronic conditions.3

Elective procedures

Today, insurance rarely covers truly elective spending (such as cosmetic surgery, alternative medicine, or Lasik eye surgery), which the consumer pays for out-of-pocket, often using credit. This part of the health care marketplace actually works well: elective treatments, as a classic consumer retail item, are available to those willing to assume the full burden of paying for them. In addition, all services not medically justified by evidence-based standards—for example, certain types of joint surgery if studies show that a lower-cost drug treatment is equally or more effective—should be paid for out-of-pocket by the consumer.

Catastrophic care for unforeseen events

Unpredictable, random, and infrequent risks (heart attacks in previously healthy patients, for example, and interventions for accidents) should be financed through traditional insurance. In such cases, consumers have limited discretion and little ability to exert downward pressure on prices—few victims of auto accidents, for example, can shop for a cost-effective ambulance service and make well-informed cost–benefit calculations about treatments. Deductibles on this type of insurance should therefore be kept low; costs are best managed by redesigning reimbursements for providers.

A provider should be compensated in one bundled payment based on the total episode of treatment, from the moment the health crisis starts until full recovery, rather than on a fee-for-service basis. Such bundled reimbursements would give providers an incentive to improve their efficiency. They would also find it in their interest to restrain costs in a reasonable way—for example, by providing cost-effective services (the correct type of hip joint, say) and high-quality treatment the first time around rather than having to readmit patients for costly corrections after botched initial interventions. Including specialists and hospitals in this total-episode-based reimbursement system will be essential. The Acute Care Episode demonstration pilot, conducted by the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, is a step in this direction.4

End-of-life care

Riders on life insurance policies might be the best way to finance end-of-life care—say, for an elderly patient with a known terminal illness—which is generally quite expensive. The insured could decide how much of their benefits to draw down at this stage rather than bequeath them to the beneficiaries. Fee-for-service reimbursement for providers would probably be appropriate, since it is hard to apply outcome measurements or evidence-based standards to many of these treatments (for instance, experimental ones).

As reform efforts move forward, the guiding principle should be to redesign the demand side (financing mechanisms for consumers) and the supply side (reimbursements and the delivery system) to align medical risks—and the attendant financial incentives—with those who can most effectively control and manage them. Reform will provide a great opportunity to restrain costs, deliver more cost-effective care, and ease the financial and psychological burden on hard-pressed US consumers. It can be undertaken fairly, we believe, if the government helps people in difficult financial straits pay for their care.