In this edition of Author Talks, McKinsey Global Publishing’s Raju Narisetti chats with Tom Gauld, a cartoonist and illustrator who makes weekly cartoons for New Scientist and the Guardian and occasional covers for the New Yorker. In his first picture book for children, The Little Wooden Robot and the Log Princess (Neal Porter Books, August 2021), a little wooden robot embarks on a quest to find his missing sister. The fairy tale, inspired by a bedtime story Gauld made up for his daughters, is brought to life with detailed illustrations, quirky humor, and magical characters sure to stir young readers’ imaginations. An edited version of the conversation follows.

Why did you want to write a children’s fairy tale now?

I’ve wanted to make a kids’ book probably for as long as I’ve been an illustrator. I’ve always liked storytelling with my pictures, and I’ve made comic books and short cartoons. A kids’ book seemed like a really fun format to try. But I never really had a story that excited me enough to take the time to make the book.

I have two daughters, and I went through that stage that a lot of parents go through when you’re reading bedtime stories to them every night, sometimes two or three short books. I had boot camp in children’s stories then, and I realized how much I loved reading the good ones, how much I hated reading the bad ones, and how important this kind of bedtime story ritual was.

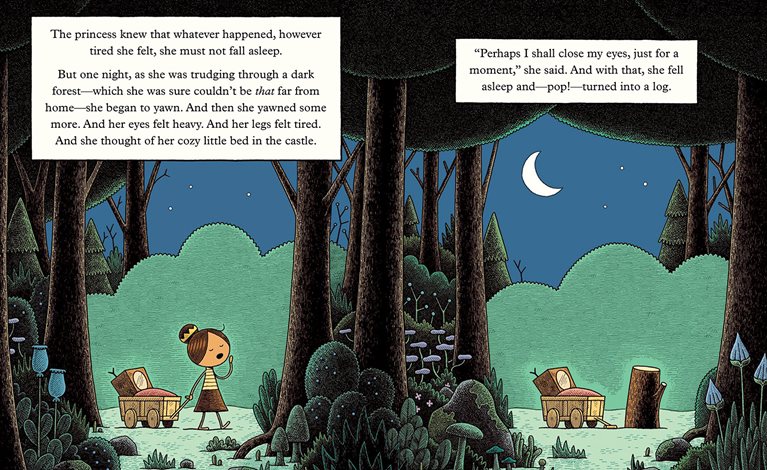

That’s what got me excited about finally committing to doing a story of my own. The fairy tale that I wrote came about through our family. My younger daughter, ever since she was a baby, sleeps like a log every night. She closes her eyes, she sleeps, and she wakes up refreshed in the morning. Almost nothing will wake her up in between. So we called her “the log,” and it was a kind of family joke.

One night, I was, as I occasionally did at the time, making up a bedtime story for the girls and improvising it. I came up with this story about a little princess who, when she falls asleep, turns into a log. So I began the project by accident in that ten-minute piece of improvisation. The girls liked the story, and I told it to them a few more times, and we talked about what we liked about it.

Making the leap

What’s been most challenging about transitioning from illustrating for adults to illustrating for kids?

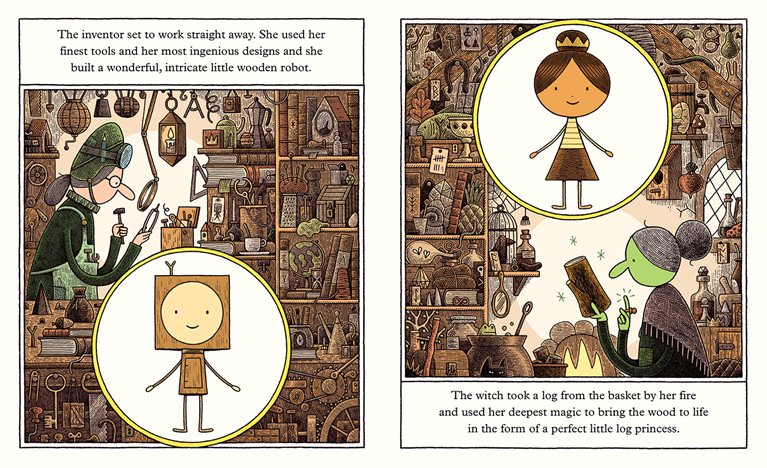

I think the hardest thing was trying to keep what’s good about my cartoons for adults—or what I like about them and what I enjoy—and translating that into a children’s world without losing what’s good about them.

I knew that a children’s story couldn’t be as dry and maybe as subtle in the same ways as my adult cartoons. And the humor would have to be a different type of humor, which could be enjoyed by a small child as well as an adult. I had to find a way to warm up some of the coolness, which is in my adult cartooning, without feeling like I’d poured a bucket of icing sugar over the top of it and without it becoming something saccharine and losing some of the charm that I hope is in my adult work.

I tried to keep the drawing style quite similar to my adult cartooning. But in an adult cartoon, I might simplify a face down to just a pair of eyes on a circle. It could be as simple as that. For a child, I think they need more than that, so there were more smiley faces. There were slightly warmer colors than I’d have naturally used, and that was a challenge, but I really enjoyed working in this new form.

How does the way you tell a story change when it’s aimed at four- to eight-year-olds?

What I had in mind was the form, which was the bedtime story—the story that’s read by a parent or another caregiver to a tired child at the end of the day. It’s almost a sort of ritual of ending the day and going to sleep. I wanted to write a story which fit the kind of age when a child probably isn’t reading to themselves and maybe can read but still has this story being told at bedtime. I really wanted to make a story which would work in that sort of space.

So my story has tiredness in it—the princess falls asleep—so it’s very much thinking about that space in which it’s told, which is a lovely, intimate moment in a family’s life. And it’s interesting to be making something to fit into people’s lives there.

In a way, aren’t you actually writing for the parents—and often perhaps tired parents?

Yes. I think if I’d written a book before I’d had children, I wouldn’t have understood so clearly that, unlike a comic book, which one reads to oneself and the story comes together in your mind silently, a children’s book is very much a script for a performance by a generally unskilled and perhaps tired actor who is the reader.

So it very much has to sound good in the mouth in a way that a comic book doesn’t so much. I really wanted it to work well and to be easily readable. So I would take drafts of the story home, and I’d read it to my children. I’d have my wife, who’s a much better story reader than me, read it to the three of us. And I’d listen to see what was working and what wasn’t working.

I didn’t dumb down the language in any way for children, but, probably more importantly, I suppose I wanted it to sound like some of the fairy tales that I’d read as a child, or had read to me. So there is some slightly old-fashioned language in there and some language that my copy editor said was quite British-sounding language for an American picture book. They were willing to let that stand because I think it fit with the fairy tale idea and the slight old-fashionedness of that type of story, which I wanted to be in there alongside my own maybe slightly stranger twist on things, like having a robot and other things like that.

How old were your daughters, Daphne and Iris, when you made up this story?

I was quite slow on this book. Between the time when I first told the story to them and the book coming out, quite a few years have passed. I can’t remember exactly how old they were when I told the story, but I would guess that was five or six years ago.

Now, they’re both teenagers. Iris is 13, and Daphne’s 16. But they’ve been there for the journey of the book all along, and it’s been very helpful having them there at the beginning, as small children who reacted quite naturally to the story, to now, when they’ve known the story all along and can help me with elements of it. It’s been a lovely family project.

Are Iris and Daphne upset that their favorite part got left out of the book?

It’s funny you say that. My first draft of the book was very long. The publisher said, “This is too long for a one-night bedtime story. If you want it to work in that form, you need to shorten it.”

It was about 3,000 words at that point, whereas the finished book is a little over 1,000. So I cut two-thirds of it. I think it shows how overwritten the first draft was that I didn’t actually lose that many things. I managed to cut out a lot of stuff that was in there which didn’t do a lot.

But there was one element—even just last night, my daughter was bemoaning that it was removed—of a very small scene when the little wooden robot is left in the frozen north on his own, and his sister is, at that point, a log, and he’s trying to find her. In my long draft, some trolls appear, and they bring him a hot sausage and a cup of tea. In my desperation to get the book down to the right length, I edited that out, which I think does help because it makes him more lonely at that point. And I also began to think, Would a robot eat a sausage?

Once you start thinking about these things, you can get in a bit of a spiral. So in the end, that scene was cut, and I think it’s better for it. But I don’t think my younger daughter, Iris, has ever talked about the book without being sad that the trolls and the hot sausage are not in it. So it may be that one day, I have to write a book about trolls and sausages to make it up to her.

I counted at least 12 other tales waiting to be told inside this one fairy tale.

I wanted to have those suggested stories nested within the main story so that even in this short, one-night, one-evening story, there’s a feeling of bigness, of a fairy tale world where there’s not just this one story going on, but there’s magic everywhere and there are possibilities. The stories are in there to help the narrative, but I also hope that they will be turned into stories, but not by me. The aim of those, really, is to spark the imagination of the child who’s being read to.

I’ve had a few friends tell me that they have had discussions with their children about those suggested narratives. One of them is called “The old lady in a bottle,” and [my friend] was saying that her son was discussing how he was going to get her out of the bottle. Does she have some knitting in there? Can she knit a ladder to get out? I really want those stories to happen, but I don’t want to be the one to write them. I want them to happen for everyone who reads the story, who can imagine what’s going on there.

Color outside the lines

The book is much more colorful, if I may use that word, than your adult work.

The book is more colorful than my usual work. I naturally move toward quite a muted palette. That’s where I feel comfortable. But that was another thing my daughters told me: “No child will want to read a book which is in your usual palette. You need more color in there.” I think they were right. So that was something I worked hard on—trying to keep colors that I liked, but just get that brightness and warmth and richness, because I didn’t want to just turn in a rainbow fairy tale.

So trying to find a way that I could be comfortable with more colorful work was one of the challenges. I took home every page of the book to my family, and we sat down and talked about the different colors, and what needed to be brighter, and what wasn’t working.

Did you aim to show a diverse family?

In terms of the race of the king and the queen and the suggested race of the children, even though the daughter is made out of wood, she does seem to be similarly colored to the mother. I suppose it comes down to the whole idea of taking an old form, like the fairy tale, that has all these wonderful, powerful tropes and using them to tell a story today.

You can’t make an old fairy tale exactly as the Brothers Grimm would have done, set in medieval Germany, because it’s now. It’s today, and that would be pointless. So I was looking at the tropes of fairy tales and thinking, What are the good ones? What are the powerful ones that I like? What are the ones which you might just put in a story unthinkingly?

The idea that fairy tales are really set in medieval Germany is nonsense. You know, there are goblins. Sometimes, St. Peter’s walking around in the forest. There are animals who can talk. They’re not real. As soon as I was freed from it being not real, I thought it would be sad if anybody looked at this book and thought it was only about German or British children.

It seemed silly not to have a diverse cast of characters. When you think carefully about these tropes, you sometimes find that they add up to something more interesting. Kings and queens were generally people from different countries who had been married in order to cement a relationship between the countries.

The queen [in the story] not being a northern European suggests the bigger world, and I think helps suggest that when the little robot is lost, he’s lost in a big, wide world. He’s not lost in a little forest in England or Germany. Sometimes, questioning the tropes which have been handed down leads to something a bit more interesting.

How did your editors help a first-time fairy tale writer?

This is my first children’s book, so I don’t know what an editor normally does. I only know this one single experience I have, which is that Neal Porter, my editor; Steven Malk, my agent; and Jennifer, the designer, all had suggestions. But they were all very gentle improvements rather than great big edits. I’d worked on the story for quite a while before I brought it to them, so I didn’t bring them a work in progress. I brought something which was as finished as I felt I could make it.

But I was expecting to have to change things, and I was willing to change things. First of all, I was delighted that after working on something on my own and with my family, that I brought it to some real professionals and they liked it. Their suggestions were subtle but very much improved [the book].

One thing I definitely had wrong in my draft is that the robot woke the princess from sleep with a kiss. He woke her as in any fairy tale, like Sleeping Beauty or Snow White. To me, a brother kissing his sister felt fine when I wrote the story. Both Neal and Steve said, “No, that just seems a bit odd. It’s not worth it.” Things have changed, and that’s a trope I see now. That’s a trope that I took on from the fairy tale and didn’t consider how it sounded in our world today.

So we changed it to some magic words, which I think improved the story, and also ties into fairy tales like “The magic porridge pot,” which has magic words said to stop a porridge pot. I like the fact that I managed to find a different fairy tale way of solving that problem.

That was the only major thing. There were little changes to the text, little improvements. They felt the ending needed a bit more visual excitement, so we added some fireworks and the people of the country standing happily, watching at the end. So it was a real whopper of an ending, whereas my original version was maybe a little quieter.

Inspiration to ideation

How did the book’s title come about?

Classic fairy tales are a big influence on this story. Before I wrote it, I wasn’t sure I could write a children’s book. I thought a lazy solution would be to find a fairy tale and illustrate it myself.

So I read all of Grimms’ fairy tales and a lot of other ones, trying to find a fairy tale that I could edit or make my own. But I found, generally, that either the very well-known ones would be uninteresting to redo—and I didn’t want to do a reenvisioning, ironic take-apart of the fairy tale—or they weren’t very well known, and they weren’t very well known because they were absolutely terrifying. Or they were really strange. Or they were brilliant, but they were just weird. I realized in the end that if I wanted to do my own fairy tale, I was going to have to write it as well. So I was totally inspired by the wonderful titles of Grimm stories.

One of my favorites is called “The mouse, the bird, and the sausage,” and it’s about a house in the woods where a mouse and a bird and a sausage live together. I love the flatness of that title. It’s so ordinary, but it’s got this insanity that there’s a sausage living with creatures.

Once I realized I was writing a fairy tale, I wanted it to have that mixture of fantasticalness and also just the flatness of flatly stating who these characters are, as if it’s perfectly normal to hear about these things.

What other authors inspired you?

They’re a writer–illustrator team called Janet and Allan Ahlberg, and he wrote the stories and she illustrated them. They wrote stories which I read as a child, and he carried on writing stories and is still alive today and writes.

I think he’s just the most wonderful writer of dialogue to be read by a parent. He was a big influence on the way I wrote the story. There’s one called The Runaway Dinner, which is a very light, rather silly story, but it’s so beautifully written, lyrically, that as a parent—even someone like me, who’s not an actor or performer—can perform a delightful act for your child just by following his words and his punctuation.

Do I spot a wee bit of your native Scotland in here?

I think that probably is in there. I grew up in Scotland near Aberdeen, and the village I lived in was called Woodlands of Durris. Our house was surrounded by forests, and I spent a lot of time with my friends walking in the forests and playing in the forests. So when I read a Grimms’ fairy tale about people wandering off into the forests, in my mind, it’s those forests of my childhood that were behind my house and that I spent lots of time in.

What do Iris and Daphne get other than a thank you in the book?

Are they getting anything? Like everybody, we’ve been in lockdown, and we haven’t traveled anywhere. The big family trip was to come to America; they’ve wanted to visit New York for a while. That’s their treat for being so good with the book this last five years.

Might we lose you forever to just children’s books?

I don’t think that’s a risk. When I started this children’s book, I had an idea for a graphic novel for grown-ups, and I had this children’s book idea, and there was a point when I realized I needed to pick one. I thought, I’ll do the kids’ book, and I’ll do the graphic novel next.

Now I’m at the stage when the kids’ book is finished, and I’m doing a little publicity for it, but I have a new space in my life for a new project, and that will be another book for adults. I’m going to keep doing my weekly cartoons for New Scientist and the Guardian.

I don’t have an idea for another kids’ book, and I don’t want to rush into one until I have one I feel as sure of as I did with this. I’ll just have to wait and see if I do another children’s book, or if it’s just this one. We’ll have to see.

Watch the full interview