Business leaders typically spend about 30% of their time on external engagement—that is, dealing with concerns of people outside their own companies or boards. By their own assessment, few are effective at this task. Which is a problem, because some of the biggest forces shaping future trends pertain to issues that transcend corporations and competition.

As my colleague Chris Bradley recently wrote, capitalizing on opportunities created by trends is a pivotal factor in business performance. Sometimes those opportunities lie in addressing significant risks and challenges. Three, in particular, have emerged as crucibles of intense concern and activity. Malevolent actors such as cybercriminals and terrorists are exposing a “dark side” to growing openness. There is also a critical need to spur middle-class advances, and to undertake the economic experiments necessary to accelerate growth and address income inequality.

Sustaining progress will demand greater collaboration and a new societal deal—one which will require business leaders to spearhead more solutions and do more to embed society’s concerns in their business priorities. “I often say it’s too late to be a pessimist,” Unilever CEO Paul Polman wrote a few years ago. “There are enormous challenges, but business leaders thrive on them and are well placed to solve them, as they also offer enormous opportunities.”

The dark side

Progress thrives on openness, and openness almost by definition means exposure. The Internet, for example, has brought critical dangers even as it has unleashed vast benefits. Everyday acts, such as connecting your phone to your car via Bluetooth, create vulnerabilities most of us do not yet consciously consider. The costs of fighting cyberthreats are rising into the trillions. Meanwhile, rogue states continue to frustrate the global community, and the strains from combating terrorism are reverberating worldwide.

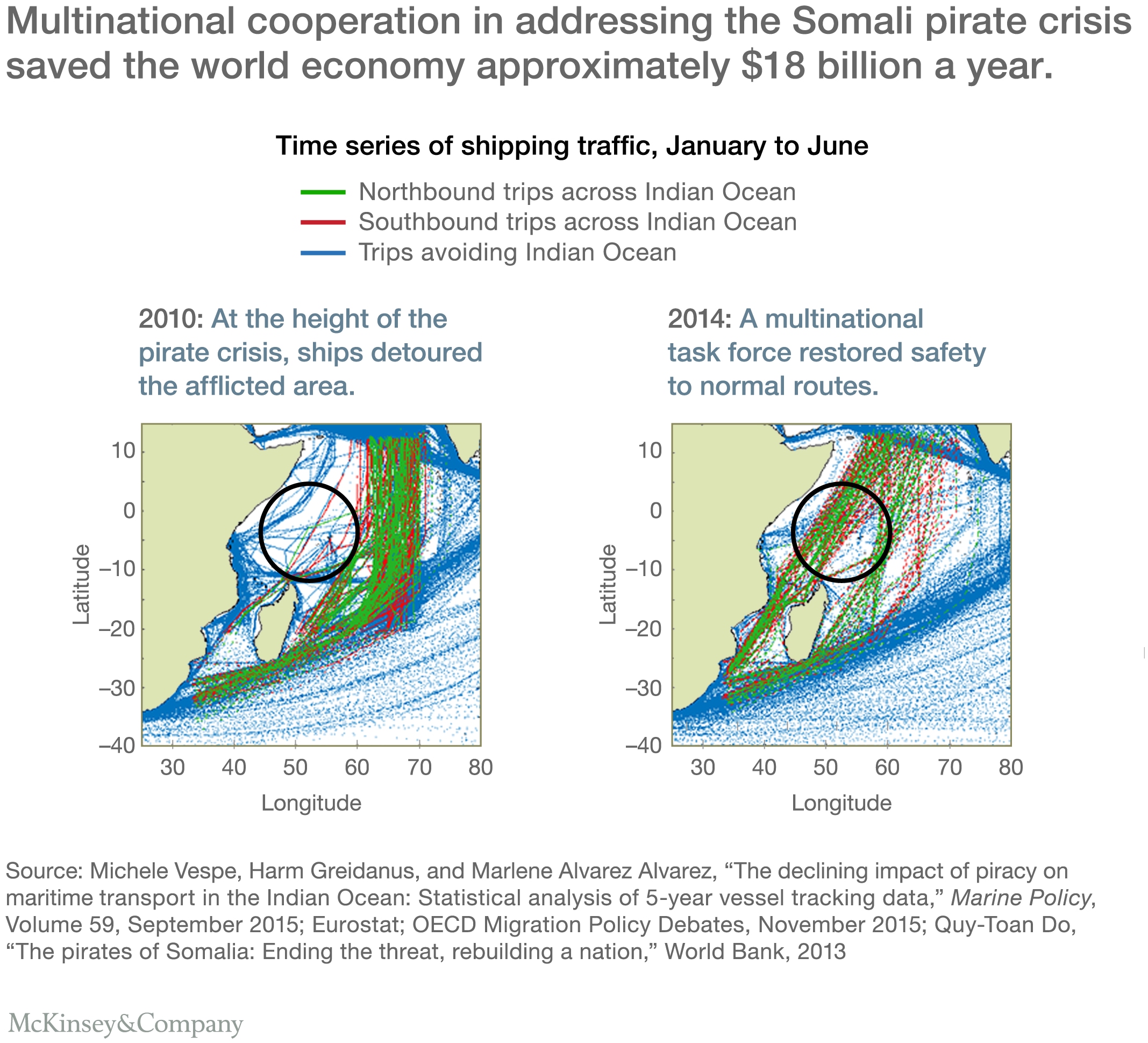

Sometimes, international cooperation can counteract the destructive power that is concentrated in the hands of a few. For example, starting in 2010, multiple states came together to beat back pirates in the Somali basin, saving the world economy about $18 billion per year.

The achievement of digital resilience also requires collaboration. In an interconnected world, companies need to explore shared platforms and sharing data about cybersecurity threats that cross boundaries of individual businesses and industries. As leaders figure out how to strike the right balance between competing effectively, guarding the corporate ramparts, and cooperating in self-defense, they will be helping to redefine what it means to live together, safely, in an interdependent world.

Middle-class progress

A central part of the narrative behind the United Kingdom’s Brexit campaign and Donald Trump’s presidential campaign in the United States was the notion that leaders of major institutions had forgotten about the middle class. Globalization and automation are polarizing the labor market, with more on the way as expanding machine-learning capabilities increase our ability to automate a wide range of tasks. As middle-wage workers are displaced, many are forced to “trade down,” which reduces their income and puts pressure on existing lower-wage workers.

There is also widening earnings disparity. Workers with advanced degrees have generally seen their incomes rise, while wages for those with only high-school diplomas have stagnated, and pay for those who lack a high-school diploma has declined. Youth unemployment has reached 50% or more in several developed economies.

Demographic trends are exacerbating matters. The number of workers earning income for each dependent is falling as populations age, making it harder for society to support the young and the old. Entitlement programs such as pension plans are woefully underfunded.

Perhaps not surprisingly, trust in leaders and institutions has fallen among the threatened middle class. Globally, 60% of working-age, college-educated, upper-income individuals express trust in business, government, media, and nongovernmental organizations, yet only 45% of the remaining population do so. Business leaders can help rebuild this trust. In fact, citizens expect this from them.

The need for middle-class progress isn’t just a developed-markets issue. As the emerging world’s new consuming class comes to the fore, it is striving for opportunity beyond entry-level roles, and finding the income polarization that often accompanies industrialization. Some of the balancing acts in the biggest rising economies that I described in my last blog, such as China’s transition from an investment-led to a productivity-led growth model, will determine the success of the middle classes in those markets.

Economic-growth experiments

While running for president in 1932 during the depths of the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt remarked, “The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands, bold, persistent experimentation.” We are on the cusp of a new wave of experimentation today, because there are no clear answers to some of the challenges looming before us.

Take growth: There is no consensus as to why it has been stuck in lower gear for years, or where it is headed. Northwestern University economist Robert Gordon argued in his 2016 book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, that the productivity slowdown that started in 1970 is likely to continue and hamper growth. Other researchers, including my colleagues at the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), argue that automation enabled by artificial intelligence, robotics, and other advances will likely raise productivity, which should increase growth.

Business leaders can help rebuild trust in societal institutions. In fact, citizens expect this from us

One thing that does seem clear is that many growth policy tools have reached their limits. Central banks and governments in the developed world responded to the financial crisis by slashing interest rates, creating innovative facilities to keep the credit flowing, and in some cases bailing out companies. Various mixes of austerity and structural reforms also were tried. When these proved insufficient to restart growth, leaders around the world turned to new, sometimes overlapping policy experiments in search of a more effective solution.

We’re entering uncharted territory in other areas, too. As the world ages, new approaches will be needed to support retirees who haven’t saved enough or are counting on pension and healthcare benefits that seem unsustainable without placing crushing burdens on the workers of today and tomorrow. Or consider infrastructure spending. According to MGI, the world will need to spend $3.3 trillion annually between 2016 and 2030 to keep up with projected growth—nearly $1 trillion more per year than we have been spending. MGI suggests that infrastructure spending can be cut by as much as 40% through better project design and execution—areas ripe for public–private experimentation.

The results of experimentation—with respect to growth, aging, infrastructure, income inequality, and more—will have dramatic implications for our world, for the business environment, and for corporate performance. Analysis by my colleagues suggests that 30% of corporate profits can be traced to social and regulatory issues, and that shares of companies that connect effectively with all stakeholders outperform their competitors’ by more than 2% per year on average. Business leaders today need to make external engagement an integral part of their strategy, to adopt long-term mindsets.

The three powerful forces I outlined demand thoughtful responses and contain the seeds of extraordinary opportunity. Leaders reaching for these opportunities will need to question their own assumptions and imagine new possibilities. Those who do will compete more effectively; they also will be better able to contribute to broader solutions, and ultimately to new and more inclusive progress.

Sven Smit is a senior partner in our Amsterdam office, leader of our Western European region, and co-author of Strategy Beyond the Hockey Stick with Martin Hirt and Chris Bradley.

This article originally appeared on LinkedIn.