In this episode of the Inside the Strategy Room podcast, Nigel Hughes discusses the challenges and opportunities consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies face in innovation. It is the latest in a series of interviews with leading innovators around the world, which includes interviews with Beth Comstock, Kevin O’Leary and Simon Mulcahy. Hughes spoke with Stacey Haas, who heads up McKinsey’s consumer innovation practice, and Erik Roth, who leads our innovation work globally. This is an edited transcript of the discussion.

Listen to the podcast:

Stacey Haas: Nigel, let me start by asking how you view the difference between being an R&D leader and an innovation leader?

Nigel Hughes: As an R&D leader, I can contribute a lot around technical insight and opportunity. But as I have developed through innovation work, I have learned it’s also important to understand how those technical issues and opportunities marry with business model and commercial opportunities. The sweet spot is the intersection between the two arenas.

Erik Roth: We hear from many innovators, particularly in large corporations, that the connection between the technical and the commercial sides is always a challenge. How do you make R&D and innovation true profit and growth centers?

Nigel Hughes: The magic lies in getting down to the basics of what you are trying to create for the consumer. It would be easy for me to walk into a room and talk in technical language and confuse people. It’s my job to ensure that I translate that technical insight into straightforward consumer language. I will give a simple example. When I walked into Kellogg, everyone in the R&D organization talked about making product. In the very first week, I said to them, “Hang on a minute: we make food. Think about what you do as making food and suddenly your commercial colleagues will be able to much better understand your brilliant technical insights.”

Stacey Haas: How does that connect to the CPG model for innovation? While the large consumer-products companies were historically very successful at innovation, they have struggled in the past few years and smaller companies have been gaining share.

Nigel Hughes: I think we have allowed ourselves to be categorized and view ourselves in a particular way. It’s interesting that we call what we do by this wonderful three-letter acronym, CPG, when actually what we do is prepare accessible foods for billions of people every day. It’s on a big scale but that does not mean that it can’t be intimate. If I look at someone as a consumer—as the C in CPG—am I really seeing them as a human being or a family, and am I getting under the skin of what they want? If I look at the product, or the P, am I thinking about food and eating and the occasions that bring us together over food? We have created structures that give the impression we are getting closer to the consumer, yet often those structures blind us to the very simple and straightforward truths. A start-up is driven by a passionate idea or hunch. We have got to recapture that energy in CPG.

Erik Roth: What structures do you think have been created that are getting in the way of this pure version of innovation?

Nigel Hughes: I often get into discussions about whether members of the R&D team should be present in certain conversations with consumers or the advertising agency. That did not exist 30 years ago when I started doing this; the interaction was much more open-door. People have found efficient models and I would argue that CPG overall is more efficient in innovation that it has ever been. The problem is, is it truly effective? What we see in the market is that it’s the start-ups pushing the ball forward.

A start-up is driven by a passionate idea or hunch. We have got to recapture that energy in CPG.

Stacey Haas: How important are external partners to your work and how do you successfully connect with them?

Nigel Hughes: Well, many external partners are keen to work with us because Kellogg has a good and long reputation. Their key problem is accessing the sort of scale that we can offer. Our challenge is, how do we work with these firms? Big companies grow up with cultures that say, “We want to own everything and the people we partner with should be thankful to be partnering with us.” I’m caricaturing but there is an element of that. Now you have to build a culture where people understand the real value those partners bring—value we could never get as quickly and effectively on our own.

Stacey Haas: For a long time, many big companies thought that longer-term innovation needed to be internally driven. You are saying it does not need to be that way and, in fact, we should be leveraging external ecosystems more.

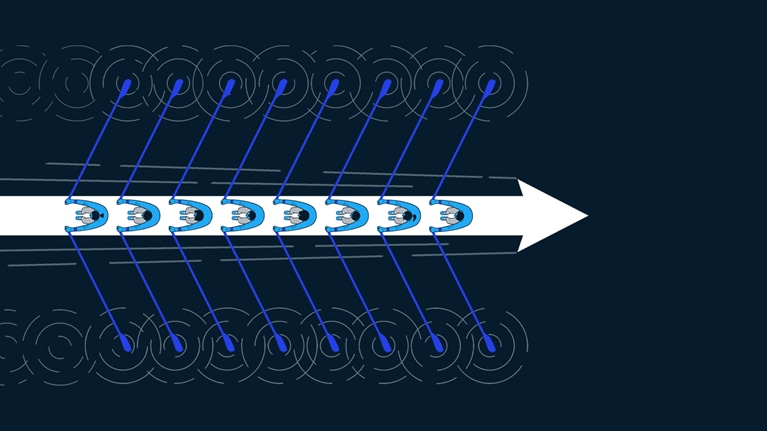

Nigel Hughes: That is exactly where I stand. I have enough gray hairs that I can pretend to have an innovation philosophy. I would call it a solution-based innovation philosophy. I picked it up by spending time on the west coast and observing big tech companies. Although their models are constantly evolving, fundamentally big tech are design aggregators, with technological components that come from other places. I see that as the best way to handle the uncertainty and opportunity of the future.

Stacey Haas: Do you have an example of a partnership with an external party that significantly helped your innovation?

Nigel Hughes: We invested in a company called MycoTechnology that produces proteins from mushrooms. Historically, Kellogg would have parked that kind of interaction purely with the R&D team and maybe checked on it once every couple of years. What we did instead was try to make the MycoTech team an essential part of not only our longer-term innovation but our immediate innovation thinking. Within 12 months of starting that collaboration, Kellogg’s food contained the MycoTech proteins. That is unheard of for us. And remember, we are talking about a start-up here, not a supply partner—we had to support MycoTech in working through their supply base. Now that relationship has turned into a whole pipeline of opportunities because we have secured, through our venture investment, access to their work.

Stacey Haas: What did you do differently in this relationship that you think made the difference?

Nigel Hughes: We accepted that even though we put venture money in, it was not a guarantee or a contractual stipulation that we would get access. That involved risk from our side, because if MycoTech found someone else that could bring their proteins to market faster, they could well have gone with them.

Subscribe to the Inside the Strategy Room podcast

Stacey Haas: I’m glad you raised the topic of plant-based proteins. It is obviously a fast-growing trend. I’m curious about your thoughts on the rapid growth of some brands in that space.

Nigel Hughes: I would characterize plant-based protein as more than a trend. I see it being a massive shift in the food space. There are three drivers: the dietary drivers, because we know that diverse plant-based proteins are better for us than certain meat proteins; environmental reasons; and, more and more, ethical reasons. I see this as being a permanent evolution. And I believe this market is only in its first generation. I draw a parallel to what happened with the dot-com bubble in the 1990s. A lot of companies started and a lot of them failed. What is happening now is the 1.0 version, and Kellogg certainly has a right to play in the meat-alternative space, through its subsidiary MorningStar Farms [that produces vegetarian food]. What is even more interesting is how people will incorporate plant-based proteins in their diets in ten years’ time. I’m not sure it will just be meat mimics.

Erik Roth: What you just described could be characterized as a hunch about the future. In the hands of a venture builder, that might turn into the next unicorn. Is that possible within the walls of a large corporation?

Nigel Hughes: That is one of the biggest challenges for large organizations: how do you manage this duality of having a major business driven by efficiency and being able to experiment in new spaces? It goes to the very heart of my job—understanding how to get that balance right.

For me, it means ensuring you invest in the short term through internal capabilities that give you those fast turn rates and drive the efficiency. Companies can have those capabilities if they put their minds to them. We have a pilot plant in Battle Creek that we used to only use for internal experiments. Recently, we got it fully validated by the FDA so we can make food for sale and implement transactional learning. It gives us an incredible opportunity to not only test and learn but serve consumers and get their feedback.

CPG is more efficient in innovation that it has ever been. The problem is, is it truly effective?

We also need to build new business models. We have a venture arm and are trying to use it to bring in that dimension. Really, we have changed completely. When I started my career, big companies had R&D centers that were invention houses. Today, we are a design house. We are about aggregating elements of the solution.

Erik Roth: You said earlier that CPGs have lost touch with consumers. At a lot of consumer companies, innovation efforts lack clarity on what problem they are trying to solve. Do you see that as well?

Nigel Hughes: Understanding the problem to solve and then who is most capable of solving that problem is absolutely fundamental. First, you have to bury your ego and say, “I am not going to be the person who solves that problem. I am going to be the food designer or the food aggregator that brings the pieces together.” The other part is, we do not live in a world of ideas; we try to live in a world of clear opportunities. Therefore, it is important to say, “I know that if I can move this brand into this space, there is a clear profit pool to go after and a clear business to be generated.” A good example is Cheez-It Snap’d baked crackers. We had great equity with the Cheez-It brand, but it was not playing in the adjacent chips area. There is a huge profit pool there, so why not? The team did a tremendous job of designing the Snap’d product to capture that opportunity.

Stacey Haas: Cheez-It Snap’d and Pop Tart Bites were recently highlighted in IRI’s New Product Pacesetters report as a Top 10 food product, so congratulations on that. What, aside from a clear opportunity, made those products successful?

Nigel Hughes: There were three dimensions. The first one we just talked about: we understood the size of the opportunity so there was a commitment within the organization to go after that space. Secondly, we approached the commercial execution in an integrated way across all channels. That was very important. You can talk as much as you like about the proposition—if you do not get the execution right, the innovation will fail. And the third part, which ties everything together, was that we knew we had winning foods. I knew that because every time you put that food in the middle of a meeting room table, it would be the first to go. That is so important, because it reaffirms the food’s quality and helps create belief within the organization at the same time.

Stacey Haas: What kind of consumer engagement did you have in creating those products? We often see R&D organizations work hard to internally optimize a product before it ever gets in front of consumers.

Nigel Hughes: As I mentioned earlier, we set up a capability at our factory to learn transactionally. That meant we not only could get the foods in front of consumers but offer them for sale. That enabled us to tweak the design and the flavor profiles of the foods based on consumers’ feedback as well as critical things such as pack sizes before we did a full launch. It was very high-touch and we want to drive more of that. We have done something similar with the more breakout idea of Joyböl smoothies. While we can be confident about a big space and a big opportunity, we will probably be precisely wrong in the initial execution, so iteration is everything.

Stacey Haas: And is iteration shortening or lengthening your development process?

Nigel Hughes: The iterations are much shorter than typical, but we do more of them so, overall, the process is shortened only slightly. But we are not worried about that because this is a new food proposition for us. We fully expect this to be worth several hundred million dollars globally over time and to be on the market for a significant amount of time, so it’s worth putting in that effort. If it were a single flavor variant of a small brand, I would want a quick iteration and the shortest development time possible.

When I started, big companies had R&D centers that were invention houses. Today, we are a design house. We are about aggregating elements of the solution.

Erik Roth: Iteration and learning presume that sometimes you will learn things that will help accelerate an idea and make it bigger, better, stronger. Other times, you learn things that suggest an idea should stop. How do you instill this sort of learning culture within Kellogg, specifically the notion that it is okay to take risks on things that may not work?

Nigel Hughes: I think there is the practical part of knowing when to quit. If we see a clear financial opportunity, we don’t necessarily stop something completely but understand that a particular route to get there is not working and continue with the aspiration by a different route. The other side is psychological. It goes back to the notion of being solution-based. I won’t say that we are all the way there but by focusing on the solution rather than the idea, there is a positive depersonalization. You still want people to be passionate, but it is important that they not associate success with their single idea and contribution.

Stacey Haas: Have you had to work with the leadership team to get support for that kind of change?

Nigel Hughes: Yes. Senior leadership is often the biggest challenge within a company because as leaders we get conditioned to only look at the hard data. The fact is, the data often is not very hard because we are talking about the future. So we have been trying to build confidence around the hunch—the idea that something is an ambitious opportunity space to go after even if we don’t know exactly how we will get there.

Stacey Haas: How do you find digital, AI, or other technologies changing the R&D process?

Nigel Hughes: They are fundamentally important. Let me give an example. One of the most important things for our consumers is understanding the ingredients in their foods and where they are from. The digital world is transforming that. It used to be sufficient to say, the wheat or the oats come from this part of the world. Now, we can tell people in which corner of which field in which country at which time this particular ingredient was grown. People want more and more precision. That matters not only in the supply chain but for R&D. Anybody can make one or two prototypes that work. When you try to produce billions of the same thing day after day, it is trickier. Being able to understand your ingredients and what processing they have been through at a granular level is critically important to us.

Stacey Haas: If you think about the future of innovation and CPG, what would you like to see in five or ten years?

Nigel Hughes: For me, there is one word and that’s personalization. Within the next ten years, we will understand that food is a personal choice, and we will be able to create foods that address individual needs and desires. The work going on around the human microbiome is absolutely fascinating. We are beginning to understand that our microbiome and metabolism determine how we respond to food from a health and well-being point of view. Equally, people want foods that are designed personally for them, and that will be a massive shift for companies like Kellogg, because historically we have made solutions that serve millions of people. I believe we will go through a transformation in the food business where we see the value created through personalization.

You can access the full podcast transcript here.