It may be that advancing technology plays the most visible role in shaping manufacturing progress in the years ahead. But we believe that what will matter at least as much for manufacturing’s future is something that’s much less visible, even though it has long been the bedrock of performance: effective leadership. How individual leaders inspire and influence others will become a key differentiator between organizations that thrive and those that do not.

Stay current on your favorite topics

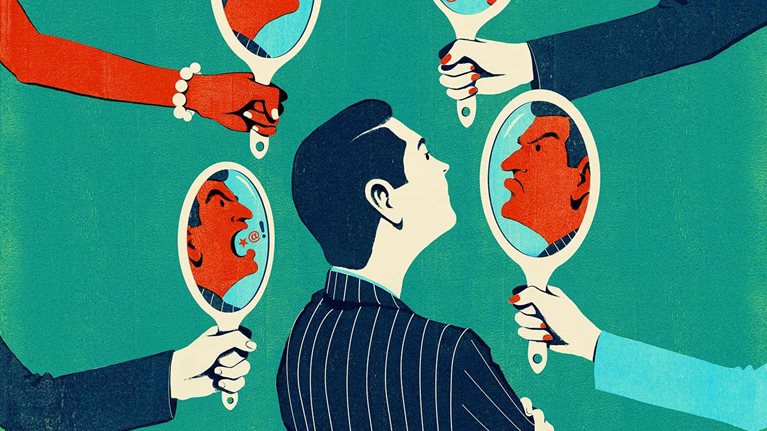

In our experience transforming large, complex organizations at scale, the bulk of the work is usually in creating operational and managerial solutions. Yet we also know that nothing will happen, let alone sustain itself over time, without effective leadership. Indeed, extensive—and remarkably quantitative—research confirms that there are roughly 20 fundamental components of leadership that correlate closely to organizational performance (exhibit).

We know that the list is hardly set in stone, and that what we define today as leadership is only one necessary part of organizational health. Yet what excites us about the list is that while some of the 20 may be seem almost self-explanatory (for example, “solve problems effectively”), collectively they actually work.

This foundation in hand, we recently interviewed colleagues with experience across a wide range of manufacturing environments, asking them what they saw as the next domains of great leadership. We all agreed that it’s impossible (and likely counterproductive) to define all the answers here; future leadership will evolve rapidly and unpredictably. But those conversations nevertheless form a call to action showing where leadership must progress in order to support change and innovation.

We found that while the 20 fundamentals will likely remain essential, manufacturers will need even more effective leadership to withstand the unavoidable forces pressing change on every level:

- The multidecade explosion in new materials, innovative process technology, labor-displacing robotics and automation, predictive-analytic tools, and vast data pools, which are now predicted to reach 180 zettabytes around the world by 2025.

- The evolution of supertransparent supply markets that have enabled widespread cleansheet costing and produced unprecedented challenges in defining products’ design attributes, cost, and pricing. At the same time, as oceans, trade barriers, and longstanding relationships recede in importance, transparent buying markets constantly raise customers’ standards around the world.

- The rise of “employee experience” in a workforce that rightly looks for more engagement, support, inclusion, and coaching and is increasingly able to draw critical comparisons with other work environments, leaders, and even industries.

- Highly dynamic political currents in which manufacturing has assumed a new prominence in policy makers’ agendas.

Against this context, we believe the fundamental profile of personal and organizational leadership is about something more than the important basics. Four attributes will enable individuals and organizations to stand out and move forward at a distinctive pace. Effective leaders will have the insight to clearly see and calibrate what really matters in operations and people; the integrity to build deep wells of trust and conviction; the courage to take on really tough opportunities quickly; and the agility to know when they need to shift course and move on. The four build on one another: when we see opportunity clearly, we need to trust each other in committing to take bold action and know that we can adapt and overcome unforeseen barriers. A leader —or, better still, an entire organization of leaders—that can combine all four well can do great things.

Insight

In our interviews, we encountered a number of closely related stories about discipline, concentration, and persistent tracking of value. Great operational leaders have an incisive sense of what matters and the ability to see constant sources of opportunity (and resistance) relative to that objective.

Dedication to value and performance can help an organization constantly orient toward the next opportunity, without getting distracted by pure novelty. This ability quickly gets an organization moving with confidence. One basic-materials company executive “had a completely instinctive sense” of the areas of performance that would fuel a rapid turnaround—targeting the uptime and reliability of specific heavy equipment, a positive trend in water and energy demand, and sustaining high safety performance.

Would you like to learn more about our Operations Practice?

At the best organizations, this disciplined sense of direction cascades powerfully to the front line: one of the authors of this article will never forget standing in a major automotive stamping line, listening to three hourly team members energetically describe how they cracked a millimeter-level defect in the stamping of an entire car-body panel. Or an example from a major healthcare player suffering from a quality compliance shock. Once the storm passed, the organization had the wonderfully stubborn discipline to return right back to the long-range productivity and cost-performance focus its leaders had championed, recognizing that far from conflicting, the cost and quality imperatives reinforced one another.

Integrity

In our work, we live in the thick of major transformations that push organizations and teams to their limits. Invariably, the programs that succeed have high-integrity leaders who model behaviors and decisions and are relentlessly consistent to their declared aspirations: on safety, productivity, or any other objective. These leaders stay true to organizational values, commitments, and each other, and they build deep wells of confidence and trust that add tremendous strength to the organization.

This “trust dividend” inspires and earns the respect of the people, who will stay the course even in tough times and accomplish great things. The dividend’s value is most obvious when things are not going well—after the exciting start gives way to the long sustainment, for instance. This genuine integrity builds organizational resilience.

At the critical point in the transformation of a basic-materials company, an executive site manager gave up her top role to personally lead a transformation that many in the company had dismissed as “just another program.” She recognized a moment of truth, took what was arguably a lower-rank role, cleaned out her office, and handed the keys to a more-junior leader. This was a clear act of self-sacrifice and a very real professional risk. Had the transformation failed under her leadership, she would have had no easy path to reinstatement. Her actions confirmed what she had been saying was the most important priority—the transformation. By taking the role of change-program leader, in a traditional organization that valued classic line-leadership roles, she strongly reinforced the transformation story.

High-integrity leaders also demonstrate a great personal generosity and humility, identifying their own personal success or a subordinate’s lapse as something “we did.” Such leaders also regularly demonstrate authentic caring and interest in their team—almost as a head of a family, speaking and acting with a distinctly personal sense of duty to their team members.

Courage

Courageous leaders demonstrate bold, informed risk taking and the grit to persist in the face of challenges. They impel the organization forward, accepting uncertainty and taking on major stretches of hard work in areas that show potential for real reward—and, more seriously, real risk of loss as well. It is the ethos of doing “the harder right instead of the easier wrong.”

In the basic-materials case, the courageous act was a determination not only to invest publicly in a major review of water use and impacts across all sites but also to publicly reach out to environmental organizations that had criticized the company. It would have been far easier to hold back, run the operation as is, and react only to a failure event.

It’s also important to distinguish bold ideas, in the pure-innovation sense that’s so visible in high tech, from bold application of those ideas in an actual business. Innovation is important; making big moves based on innovation, including decisions that may involve long-term and even irreversible outcomes, is another matter. Ford’s dramatic decision to convert its global best-selling vehicle, the F-Series pickup trucks, from industry-standard steel to aluminum, illustrates the point well. Ford changed far more than a material: it changed its supply-chain structure, its tooling, its procedures, and its entire workforce experience. We saw a similar story at a heavy-vehicle manufacturer that made a bold bet on an entirely different assembly process that, counterintuitively, increased its flexibility and speed.

While most organizations will eventually progress toward better, more advanced ideas, it is speed that sets some apart. We see too many examples of cautious leadership creating long, multiyear gaps between the recognition of a great idea and real adoption. Successful organizations also have the grit to move beyond the idea or the proof-of-concept pilot to implementing at scale.

The great re-make: Manufacturing for modern times

This 21-article compendium gives practical insights for manufacturing leaders looking to keep a step ahead of today’s disruptions.

Boeing provides a great example in its adoption of moving assembly lines for whole-aircraft manufacturing. Traditionally, airplanes were built in single, old-school stations, absent much of the rigor typical of high-volume assembly lines in the automotive sector. The idea of moving lines in aircraft assembly took hold in the late 1990s for the comparatively low-volume Boeing 717. Boeing then adapted the idea to its core 737 production lines, and then to the far more complex production of the 777. Testing a moving line is hard work, and deploying a new operations model takes courage—the kind of bold path that might not normally be taken.

A similar path is currently unfolding at SpaceX, whose Falcon rockets and Dragon capsule spacecraft have already helped dramatically reduce the cost of orbital delivery. Yet aggressive levels of design cost targeting are just part of the story, which also relies on major progress in new technologies such as advanced friction-stir welding, and a determination to in-source virtually the entire production process at US wage rates. The company’s willingness to absorb substantial risks and recover quickly from setbacks has thus far kept it on track to achieve its ambitious mission of launching humans—potentially to Mars.

Agility

Great military leaders recognize that no plan, regardless of preparation, survives first contact: “the enemy always gets a vote.” The world is under zero obligation to conform to any leader’s strategy. Great leaders and organizations have the humility, situational awareness, and organizational skills to adapt to the world as it is and as it evolves. They combine flexibility with a disciplined ability to look down-range to see real and imagined bumps in the road, both threats and opportunities.

Retired astronaut Fred Haise, one of three flight crew on Apollo 13, recently shared an experience. On April 14, 1970, the crew’s moon mission aborted when a cryogenic oxygen tank exploded, catastrophically disabling the vital Service Module spacecraft. The odds on a safe return were extremely long.

Haise spoke about the apparent lack of contingency plans and the now-famous problem-solving struggle to bring his crew home. He was clear: the reason there was no backup plan was not because someone hadn’t imagined the failure—it was because NASA had determined this type of event to be nonsurvivable. Haise’s personal story is an iconic example of agile leadership: a team adapting to the world as it is and not as they planned it to be. The team demonstrated the humility necessary to discard an original, deeply invested plan; oriented itself quickly (in a matter of minutes) to a new situation; adapted; and overcame. Agile leaders hold fast to a clear intent (value, innovation, or any other goal) but quickly and intelligently create new plans that rely on new insights, better ideas, and more reality. Like that Apollo flight crew, they constantly solve problems and keep going.

From four to more

Insight, integrity, courage, and agility—backed by the 20 fundamentals—will help serve as the practical navigational points for innovative future leadership. While there are no textbook answers to what this will look and feel like, a few essential questions can help organizations begin to think about what they will need of their leaders:

- How can a leader and a team create the space, mindfulness, innovative relationships, and objectivity that foster insight?

- What can build our integrity, trust, and a moral and professional sense of purpose of who we are, what we do, and why we are so deeply committed?

- What can increase our courage to confront tough situations and high-risk opportunities positively, even amid genuine fear?

- What will allow us to see, understand, and rapidly recalibrate to a shifting landscape in ways that progressively challenge our people?

Much of what will be called innovation will actually be the recycling and rediscovery of existing ideas—perhaps in digital or even robotically supported formats. But that adaption is itself an innovation worth doing. Whatever form it takes, the next horizon of operations leadership will increase the velocity of organizational performance, particularly in the deeply technological, high-stakes and (still) very human environment of 21st century manufacturing.