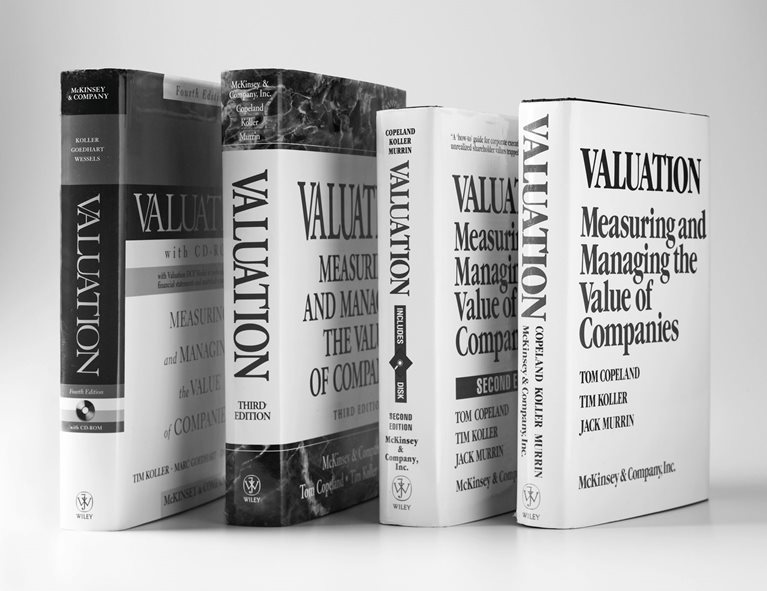

From its humble 1988 beginning as a three-ring binder shared internally, “Valuation,” has gone on to become the definitive reference for leaders who want to create value, and investors around the world sizing up companies for investment.

The book, which has sold more than 1,000,000 copies across 10 languages, has just been re-issued for the seventh time. We caught up with McKinsey partner and “Valuation” co-author Tim Koller to find out why this book endures and what's different in this latest edition.

Before we get into Valuation, tell us a bit about your background.

I grew up in San Diego California, one of four kids. My dad worked for an aerospace company and my mom for a school and the state highway patrol office. After college in LA, I earned an MBA from the University of Chicago and went to work in the energy industry and then consulting.

What was the original inspiration for this book?

I joined McKinsey in the late ‘80s, and there had been a wave of acquisitions—some hostile. The firm needed a consistent way of helping clients analyze the performance of and valuation of companies and whether they might be a target. The situation was very similar to the activist investor activity we see today. There were no books—no one knew quite how to do this.

Early on in my career, I had helped to pioneer an approach that converted traditional accounting statements into the cash flows of a business, so one could truly understand what a company was worth.

We compiled our knowledge and techniques into a 3-ring binder, and distributed it to our newly created corporate finance team. As we used it again and again, interest grew in publishing it through word of mouth. We converted the 3-ring handbook into a comprehensive book that was published in 1990.

How big was the first run?

Twenty-thousand copies. It was a such a narrow-interest topic.

And today it’s sold over a million copies. What accounts for its success?

Plain language, practical step-by-step guidance, lots of examples. The book explains in simple terms how to combine and apply finance, accounting, economics and strategy principles to measure the value of a company. It also draws a clear link between these principles and the practical work of creating strategy, managing portfolios, and structuring capital. We use real-world examples to show how growth and return on capital drive cash flows, which in turn create value. Also, we analyze the current, overriding economic, geopolitical and societal events that are influencing business at the time.

A lot has happened since the last edition in 2015. What topical issues are we are seeing in this edition?

We added some new thinking the importance of long-term decisions as a factor in creating value, as measured by McKinsey's Corporate Horizon Index. Though it’s helpful to point out that we’ve been emphasizing the importance of long-term thinking since the first edition.

We also look at the value that environmental, social and governance (ESG) initiatives can bring to a company, if managed correctly. This means companies need to widen their aperture and focus on all stakeholders - not just customers but also employees, partners, suppliers, citizens.

Since there are innumerable ESG initiatives, the greatest value, we believe, will come from focusing on a few that are directly relevant to the business. For example, an apparel company should work on developing a sustainable supply chain or a beverage company might work on water consumption.

And we offer guidance on how to value digital initiatives—only 16 percent of companies found their digital efforts resulted in lasting performance improvements.

That’s surprising. What makes valuing digital so tricky?

Digital can be fuzzy; it can mean anything from a tech upgrade for productivity to analyzing the real value of a “billion-dollar unicorn.”

But the fundamentals are straightforward: how much cash flow does a digital program create? How does this compare to an alternative initiative? Or to doing nothing?

Many times, a company undertakes a digital project, say a new channel for customers, which may not bring in additional revenue, but it adds value because the alternative of not doing it means losing your market position. It’s the cost of doing business.

This edition was in production before COVID-19 hit. How are you advising CEOS today?

We recently interviewed 10 long-term investors about exactly this: what primary piece of advice would they give to CEOs? They said…

Everyone is looking at what you are doing now—and investors and stakeholders have long memories. How a CEO treats their people, their suppliers and their customers during this crisis will affect their reputations for a long time. One retailer had put its people at risk keeping stores open longer than prudent: this caused an investor view them negatively.

Don't think about this year: focus on coming out stronger in 2-3 years. Hire talent from weaker companies, keep your product development going to maintain or build a competitive advantage over shorter-term-oriented competitors. It's a unique opportunity to put your long term-thinking to the test.

Tell us a bit about your co-authors

We were pioneers in remote working before COVID, because we were never in the same room together working on the 7th edition. Marc Goedhart, who is a senior knowledge expert in McKinsey’s Amsterdam office and David Wessels, today a professor at the Wharton School, have a unique background combining both academic and practical experience. We’ve know each other for more than 25 years and collaborated on the 4th through 6th editions. Because we’d worked so closely before, we could work remotely without losing any effectiveness. And we couldn't have done it without our two editors, Bill Javetski and Dennis Swinford.

On a final personal note, how did you spend the quarantine?

I live in rural Connecticut and there were 7 of us together in our house – my immediate family of 3 adult daughters, plus a friend and boyfriend. We hadn’t lived together for years so it has been really nice – lots of comfort food and pickle ball.