In an age of regular technological disruption, for software companies, growing fast has become essential to survival. In these interviews, Anaplan CEO Frederic Laluyaux, Jive Software executive chairman Tony Zingale, and Synopsys cofounder, chairman, and co-CEO Aart de Geus discuss how important it is for software and online-services companies not only to zero in on their main priorities but also to be prepared to reevaluate products and processes as they grow. They also explain why growth alone isn’t enough and why software companies must target becoming profitable rapidly and efficiently. The interviews were conducted by McKinsey director Eric Kutcher, and edited transcripts of their remarks follow.

It’s ‘grow fast or die fast’: Anaplan’s Frederic Laluyaux

Challenges of growth

Well, there are many challenges. The first one is to build the momentum, right? So you hired your first few people, you built the vision, and you have to start hiring the talent and hiring the right people who are a good cultural fit for your growth and your speed. Realizing that is a first element.

The second is to enable the processes to actually come in early. Even though you are an early-stage organization, you have to bring the processes in early to enable that growth and limit the chaos. I mean, you tolerate a bit of chaos when you’re a hypergrowth organization, but given who you’re serving and given the scale that you’re trying to establish right away, you have to bring processes very early, which is not a natural thing for a start-up.

I think the first thing is build a culture, bring the processes, and bring the talent in the organization. If you manage those three things correctly, and you stay focused on your core values, you have a good recipe.

Grow fast or die slow

Software and online-services companies can quickly become billion-dollar giants, but the recipe for sustained growth remains elusive.

The global mind-set

I said from day one that we’re building a small, global company versus building a company in North America and saying, “Oh, we’re going to internationalize the company.” We went global from the get-go. But that gave us the muscle and the ability to support those big customers.

And now, the market is basically switching to calling Anaplan and pulling us into opportunities. So it was absolutely critical for us to grow so fast and take a bit of a leap of faith. You have to believe that your technology will scale and will be relevant for companies around the world.

The last thing I would say on that topic is when you sell to Fortune 1000 organizations, the problems that they face in Singapore are the same problems that they face in France and in the US. I knew that the problem we were addressing was global. The problem of planning and executing your strategy is global. There is no point in waiting.

If you have a good solution for companies in North America, that same solution will apply to the companies in Singapore and in Australia, in France, in Germany, and so on. You want to capture that market, and there is no reason to wait.

Grow fast or die slow?

I think it’s grow fast or die fast. In the world that we’re disrupting, the die slow is not really happening. You have to grow really fast. If you have a solution that fixes a global problem, you have to go global right away. You have no choice, otherwise someone else is going to take that spot.

You want to capture the market, you want to build the relationship with your customers right away. The companies that you are disrupting, I think they’ll die fast, not necessarily slow. But that’s not what I wish for them.

Frederic Laluyaux joined Anaplan as CEO in 2012. He was formerly a general manager and senior vice president at SAP Applications, having started his career leading ALG Software’s global operations until that company was acquired by Business Objects in 2006.

Focusing on future profitability: Jive Software’s Tony Zingale

Growing fast

Growth is the essence of driving shareholder value, actually, if you’re a public company. But even as a private company, you have to be fixated on your growth agenda. You have to be clear on what your market opportunity is, what the buyer criteria is to acquire your offering of software—and, in this case, services as well—and be able to defend and beat the competitive challenges that you’re going to have in your marketplace.

But the underpinning of this is to go as fast as you possibly can. Certainly the technologies of today, and some of the technology disruptions we’ve seen, specifically around cloud, mobility, social networks, and big data aspects—these are all of the attributes that are driving purchase decisions.

So finding the strategy that fits all of those at Jive Software has been something that we’ve been able to take advantage of. In any given period of time since we’ve been public—growing anywhere from 25 to 50 or 60 percent—growth is the agenda that disruptive-technology companies have to have at the top of their list.

How do you manage growth?

You manage growth very carefully. You have to have a great leadership team. You have to have people that have, I know it sounds cliché, but have done it before—been there, done that, people that are capable of leading large technology organizations. We have more than 250 developers and four or five different locations for even a small company like ours. So the leadership and engineering needs to be adept at doing that. They can’t be learning on the job, if you will.

You know, the sales and marketing aspects of the company—which is probably the other large investment both with respect to people and in overall capital that the company’s utilizing—have to be world-class in their ability to create awareness, buzz, brand appeal, and affinity as well as be able to take advantage of that from a selling and go-to-market point of view.

So a great leadership team, but you also have to be very crisp with your vision and strategy from the top. You have to be clear on what we’re focused on—and what we’re not focused on. So many times companies want to do 25 different things, or even 10, or even 5. Where, at the end of the day, it’s 2 or 3 that you have to be exceptional at.

The path toward profitability

Grow or die, right? We have to continue to grow. At the same time, now that we’re public, there has to be growth with a vision and a path toward profitability. The pendulum always swings back and forth in the public markets. It’s grow at any cost for a while—if you can grow at 100 percent a year, or if you can’t grow at 100 percent, something more meaningful, 20, 30, or 40 percent—you need to grow with a path toward making a profit and returning some of that investment back to the shareholders in some way and some fashion.

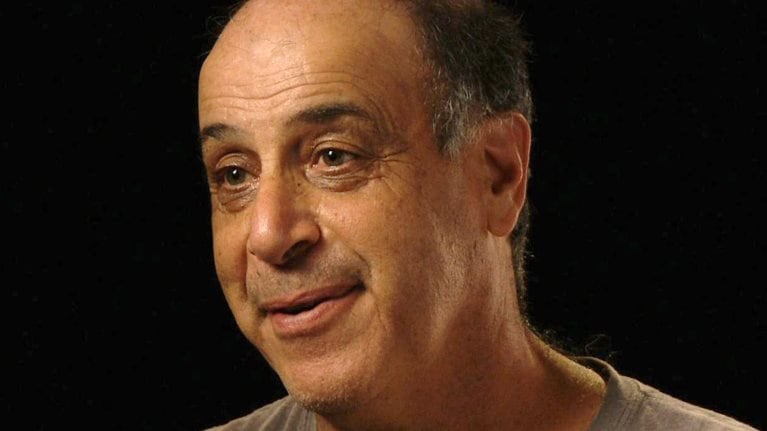

Tony Zingale is executive chairman of Jive Software, having retired in 2014 after more than five years as CEO. Zingale was previously president and CEO of Mercury Interactive, growing the company to more than $1 billion in annual sales before overseeing its $5 billion acquisition by HP in 2006.

What change management means: Synopsys’s Aart de Geus

From start-up to world leader

I had the opportunity to start the company roughly 28 years ago. I don’t look at it as one company; I look at it as many different companies, because each stage is so different. The growth is what makes it possible to broaden the impact, and impact is what makes it possible to grow again.

It is far from simple to keep doing that on an ongoing line. The reality is it comes in waves, and each of those waves brings about strategic challenges, execution challenges, globalization challenges, and people-evolution challenges. What is so exciting about managing against these growth expectations, requirements, or desires is that at any point in time you need to be constantly watchful of each of these aspects and make them evolve.

The reality of growth

The reality on most markets is they are finite. We always look at those stories that right now are in this incredible, unimpeded growth. But for many markets, that’s not the reality. It goes really well, and then it becomes more difficult, and then you have to do something different.

The difference sometimes means you have to reevaluate your product, and so you can continue with that. The difference can sometimes be to look at adjacent markets or to even go further away. The further you go away from where you started, the more opportunity there may be, but the more there may be risks of execution, of having the right talent, the right position.

That is called strategy—how you balance investing in where you’re already strong, and potentially harvesting more profitability out of that, versus investing in something new and emerging that invariably starts by being unprofitable and then gradually grows. That’s now our portfolio, and larger companies are clearly always in that situation.

Shifting toward profitability

There’s an enormous amount of emphasis on growth with the assumption that later on you can translate it into profitability. I think that one has to think much more about balance, which is that if one doesn’t have a perspective of how to get profitability at some point in time, it becomes both culturally and execution-wise very difficult to bring it in later. Because customers love it when you provide great stuff at no cost to them. But telling them later, “Oh, now you have been using our stuff, we’re going to charge you more and more,” is not the greatest way to build great customer relationships. There’s always a balance between those two.

There is no question that if you have the good fortune to be in a market that’s growing, that makes things a lot easier. There’s no question that if you have the fortune to have a product that’s doing very well in a market that’s not growing, that’s also good. The reality is sometimes you have a market that’s not growing and you have a lot of product challenges—and you still have to execute well.

Growth is absolutely a good objective for the trajectory. It’s just that in reality, companies do go through waves. Top management is being appealed on, at the moment that you’re on these transitions. Change management is the most difficult type of management. It is quite remarkable how, in many companies, every time there’s change management, they change the management. That, I think, is not necessarily great management.

Aart de Geus cofounded Synopsys, an electronic design automation company, in 1986. He has received numerous industry and community honors, including being named Electronic Business magazine’s CEO of the Year in 2002. De Geus created the Synopsys Outreach Foundation in 1999, which promotes project-based science and mathematics learning throughout Silicon Valley.