The health care industry faces daunting challenges. Across developed countries, cost inflation continues unchecked; the average US household, for example, spends more on health insurance than on mortgage repayments. Profound quality and safety problems persist—there are about 90,000 avoidable deaths a year in the United States alone.1 Many health systems face recruitment challenges despite large pay raises for doctors, and an increasing number of clinicians say they would advise young people against choosing careers in medicine.2

So further change is still needed, despite years of progress in the quality of health care around the world. This transformation will require leadership—and that leadership must come substantially from doctors and other clinicians, whether or not they play formal management roles. Clinicians not only make the frontline decisions that determine the quality and efficiency of care but also have the technical knowledge to help make sound strategic choices about longer-term patterns of service delivery.

Unfortunately, the conventional view of health care management divides treatment from administration—doctors and nurses look after patients, while administrators look after the organizations that treat them. But we can learn from a number of pioneering health care institutions that have achieved outstanding performance by radically challenging this assumption.

Our research also highlights the powerful barriers that hold back the development of effective clinical leadership. Understanding these barriers offers pointers toward the best ways to build clinical leadership across health systems.

Why clinical leadership matters

Consider the case of Kaiser Permanente, a large US payer and provider operating in several states. In the late 1990s, Kaiser Permanente Colorado was struggling with worsening clinical and financial performance and losing top doctors to private practice and rival organizations. A new executive medical director—Jack Cochran, a pediatric plastic surgeon—made clinical leadership an explicit force for improving outcomes for patients. Defining the role of the clinician as “healer, leader, and partner,” he revamped Kaiser’s leadership-development programs for doctors. Within five years, Colorado had become Kaiser’s highest-performing affiliate on quality of care and a beacon of quality within US health care. Patients were significantly more satisfied, staff turnover fell dramatically, and net income rose from zero to $87 million.

The Veterans Health Administration, within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), provides another example. Established as a public-sector health system for retired military personnel, it was performing so poorly in the mid-1990s that some prominent voices suggested closing it down. A new CEO—again a doctor—sponsored an improvement program in which clinical leadership played a central part. Ken Kizer reorganized the Veterans’ Health Administration into 21 networks, each with accountable clinical leadership, across the United States. The program also introduced clinically relevant performance measures, with corresponding rewards, and new information systems, including one for electronic medical records. The VA soon became a leader in clinical quality: for example, the risk of death for men over 65 in the VA’s care is 40 percent lower than the US average. The satisfaction level of patients rose to 83 percent, 12 percent above the national average, even as the VA’s patient numbers doubled over the following decade.

What do these and similar examples tell us about clinical leadership? Improvements happened because clinicians (most notably doctors) played an integral part in shaping clinical services. This expanded role did not come about through one-off projects; nor were changes in formal job descriptions the primary driving force. Rather, what changed for clinicians was their professional identity and sense of accountability. All staff, whether clinicians or not, came to share a common aim: delivering excellent care efficiently. Doctors collaborated with administrators on important clinical decisions—such as how to expand or reconfigure services—in full knowledge of the trade-offs and resource implications.

Even more thought was given to patients and their needs—for example, clinicians not only paid attention to clinical outcomes for patients but also further emphasized the overall quality of the patient experience. The performance of clinical units was tracked in real time. A lapse in safety, rather than being explained away, triggered a multidisciplinary conversation to help learn lessons for the future. There was a sense that clinicians were, more broadly, extending the responsibility they feel for their patients to the organization itself.

A growing body of research supports the assertion that effective clinical leadership lifts the performance of health care organizations. A recent study by McKinsey and the London School of Economics,3 for example, found that hospitals with the greatest clinician participation in management scored about 50 percent higher on important drivers of performance than hospitals with low levels of clinical leadership did. In the United States and elsewhere, academic studies report that high-performing medical groups typically emphasize clinical quality, build deep relationships between clinicians and nonclinicians, and are quick to learn new ways of working.4 A recent study by the UK National Health Service (NHS) found that in 11 cases of attempted improvement in services, organizations with stronger clinical leadership were more successful,5 while another UK study found that CEOs in the highest-performing organizations engaged clinicians in dialogue and in joint problem-solving efforts.6

In many ways, this evidence is unsurprising. Large health care systems and providers rely on complex and rapid decision making from thousands of people hundreds of times a day, often with life-or-death consequences. A command-and-control approach to leadership is untenable in such a complex and uncertain environment: it is impossible to determine, from the top, the right decision in any given situation. Distributed leadership models reap benefits by enabling people to make effective decisions locally, guided by the organization’s overall aims and norms, without the need for excessive bureaucracy and top-down intervention (see sidebar, “The virtues of distributed leadership”). In essence, the most successful health care organizations treat all employees as potential leaders in their own spheres—and not least the clinicians.

What stands in the way

Despite accumulating evidence of the positive impact of clinical involvement in the delivery and improvement of service, health care organizations often struggle to achieve this kind of participation. To understand the barriers to clinical leadership, we conducted interviews and workshops involving nearly 100 clinical professionals. Our research highlighted three main issues.

First, we found an ingrained skepticism among clinicians about the value of spending time on leadership, as opposed to the evident and immediate value of treating patients. Participants explained that playing an organizational-leadership role wasn’t seen as vital either for patient care or their own professional success and therefore seemed irrelevant to the self-esteem and careers of clinicians.

Moreover, many participants expressed discomfort with knowing that the impact of clinical leadership is often hard to prove. Clinicians develop a skeptical mind-set about changes to treatment approaches—a mind-set that is rooted in the precept, “first, do no harm.” They also have a clear view of what constitutes robust evidence—one that is rooted in evidence-based medicine for clinical interventions. As compared with biomedical standards (particularly randomized controlled trials), clinicians see the study of leadership as fundamentally ambiguous, even weak. This attitude becomes entrenched early in people’s careers (in medical school, typically, for doctors), and there is no concerted effort to broaden it later on.

Second, it became clear there were weak or even negative incentives for clinicians—especially doctors—to take on service leadership roles. Leadership potential generally isn’t a criterion for entry into the clinical professions and often isn’t a major factor in promotion. Nor is there a well-defined and respected career path for those with an appetite for formal leadership roles—in stark contrast with well-trodden clinical and academic tracks. Peer recognition is low or nonexistent: those who reduce their clinical practice to take on formal leadership roles are often described by colleagues as having “gone over to the dark side.” The difference between leadership and research is instructive: the latter is well systematized, its importance in clinicians’ careers is widely recognized, and the incentives to undertake it are clear: research publications are crucial to securing the top jobs or professorships, which carry great prestige and influence and (frequently) financial rewards.

The financial disincentives for doctors to take on organizational leadership roles is illustrated by the NHS, where salary scales are lower for managers than for doctors and where devoting time to leadership activities may reduce the scope for income from private clinical practice and even jeopardize research funding. And because measurement of the quality of care has been rudimentary, it has been impossible to reward those who build the best services.

Third, we found little provision for the nurturing of clinical-leadership capabilities. Organizations generally lack meaningful processes for finding, inspiring, and stretching those clinicians who possess the greatest potential as leaders. Leadership and management training is frequently absent from core curricula for undergraduate or postgraduate trainees and for the continuing professional development of clinicians.

The programs that are available to clinicians are often run externally rather than in house, making it harder to focus the development experience on the real day-to-day challenges participants and their services face, reducing relevance, and hindering the translation of learning into action—especially important given the lack of follow-up support in the workplace. The biases of clinicians are at play as well: having had years of training to perform their clinical role, many assume that months or even years of formal training are needed before anyone can safely be let loose as a leader.

The path to leadership

Despite an explicit focus on clinical leadership across many health systems, traditional ways of working and mind-sets become so entrenched that many health care organizations struggle to develop clinical leaders successfully. But some straightforward measures can yield significant results.

Shifting beliefs

Perhaps the highest barrier to the greater involvement of clinicians in shaping the future of patient care lies in the historical beliefs of clinicians themselves about the value of leadership and management. One way to address this problem is to be far more systematic about gathering stories, told authentically and compellingly by those who participated or observed, that highlight the value of great clinical leadership. By “making heroes” of clinical leaders of all types, both in formal management and in frontline roles, organizations can create a stronger bank of role models and also spark a sense of possibility. These stories should highlight the benefits both to patients and to the teams delivering care—benefits such as greater autonomy or simply the sense of pride in achievement. In Boston, for example, Partners HealthCare celebrates distinctive clinical leaders not only at annual award ceremonies but also day to day, through e-mail, in-house journals, and informal conversations.

Health care organizations need to build a solid, credible evidence base to show the importance of clinical leadership. While approaching the topic as though it were a clinical trial is difficult, organizations should track measures of clinical-leadership development and correlate them with their impact on quality and costs. Regional health care systems or authorities have an influential role to play here, given their scope for pooling analysis across a number of organizations.

Creating the right environment

To create the kind of evidence base described above, health care organizations need, at a minimum, basic performance data from which meaningful comparisons can be made. Sound, transparent performance information will also encourage clinicians to play a wider role in making decisions about the best ways to care for patients and to manage resources. Many organizations have found that circulating clinician-level performance data—whether made anonymous or not—prompts competition among clinicians, which in turn encourages them to become involved in improvement efforts. Generally, the health care sector lags behind others in implementing the infrastructure and processes that could provide such basic information. There are exceptions, however: a substantial investment in systems for generating reliable, timely performance data underpinned the transformations described above at both the VA and Kaiser Permanente.

Policy makers and organizations must also retune incentives—above all, by removing egregious disincentives for clinicians to become service and system leaders; these disincentives include paying clinicians significantly less in such roles than they would make by remaining in full-time clinical practice. Correcting these problems is important not only for direct financial reasons but also because of the wider signals that incentives send about the value and prestige attached to clinical leadership. Where it flourishes, in organizations such as Health Partners, in Minnesota, clinicians in formal leadership roles typically receive a small premium over colleagues who focus solely on direct patient care. Too great a financial premium, however, would make patient care less attractive and damage what ought to be the peer-to-peer relationship between leaders and other clinicians.

As people come to appreciate the link between performance and enhanced clinical leadership, health systems can also encourage it indirectly by finding appropriate ways to reward organizations that perform well and by creating meaningful consequences for those that don’t. The VA, for instance, operates on the principle of earned autonomy: high-performing regions and organizations receive substantial freedom to operate with less central oversight, whereas those that underperform are scrutinized closely.

Supporting real learning

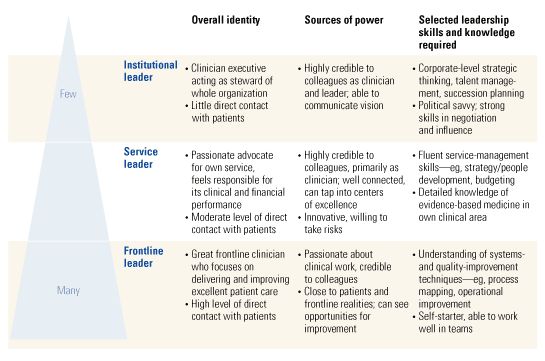

Any effort to encourage clinical leadership has to include support for professional development. But (perhaps surprisingly) the best starting point is not to create or commission a training course. Health care organizations must first define what they want from their clinical leaders—what skills and attitudes they hope to encourage, whether there are differences across professions or roles, and where the need to develop leadership is greatest. They can then target their efforts wisely and help clinicians identify and overcome any shortcomings.

The US Army’s West Point Leadership Academy, for example, recruits, trains, and develops leaders in accordance with the explicitly defined leadership model of the army and its threefold “be, know, do” philosophy. From the moment new trainees arrive at West Point, this model is emphasized, along with the need for trainees to demonstrate that it has an ongoing influence on their development. Some health care organizations with a development focus have made their expectations similarly explicit: Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust, in Birmingham, UK, and New York Presbyterian Hospital have worked hard to define their expectations of clinical leaders at different levels. This enables them to target their development programs very precisely and to create enough leaders to meet their organizational needs.

As with all training efforts for adults, it will be necessary to address the practical issues clinical leaders face. There are obvious benefits to programs that are truly centered on real work: the power of learning by doing, the importance of immediate feedback, the integration of concept and application, and the encouragement that comes from seeing a tangible impact. And for clinicians, development programs with real work at their heart can help enormously in demonstrating how patients benefit when clinicians lead the improvement of services. A leadership program involving a dozen UK hospitals and both clinical and nonclinical staff, for example, focused on redesigning pathways (strict treatment steps) for patients with stroke and hip fractures. The program, positioned as a quality-improvement effort rather than a training or development course, had a remarkable impact on lengths of stay, mortality rates, and costs—all of which fell by up to 30 percent. It also created enthusiasm for leading service-improvement efforts more generally, with enduring benefits after the formal program had ended.

The most powerful clinical-leadership initiatives go even further, with integrated development journeys tailored to the evolving needs of individuals. At Kaiser Permanente, the choice of technical skills covered in leadership programs matches the participants’ self-identified needs: for example, the head of a primary-care clinic might be trained in scheduling, multidisciplinary teamwork, and group visits. Physicians with particular strengths, such as interpersonal effectiveness, are asked to share their expertise by teaching colleagues. Leaders don’t receive just a single boost; a series of interventions reinforces their development over time, creating groups that learn together and make the link to real work.

For more formal leadership-development programs, health care organizations should consider introducing processes to select participants in order to underline the value of the programs and, more broadly, the prestige associated with being on the organizational-leadership track. For example, Singapore’s National Institute of Education (NIE) sifts through the whole teaching workforce to identify high-potential candidates to be future head teachers. Entry into the head-teacher track is highly competitive, and a series of gates determines a candidate’s subsequent progression. This approach helps signal the value the NIE attaches to teachers who step up to become leaders.

Starting from isolated pockets of excellence and innovation, clinical leadership still has a long road to travel. But it is an essential road for both clinicians and their patients. A deep commitment to patient care and to traditional clinical skills will always remain the core of a clinician’s identity. To achieve the best and most sustainable quality of care, however, a commitment to building high-performing organizations must complement these traditional values. All the evidence suggests that patients will see the benefit.