Oil and gas companies are in a race to develop and scale energy solutions that will pave the way for a greener world. To enable the net-zero transition, companies are reimagining nearly every aspect of their businesses, from partnerships to talent and innovation. Doing so requires creating the right conditions to foster innovation, as well as investing in the right resources.

McKinsey’s Dara Olufon and Kassia Yanosek spoke with Aleida Rios, senior vice president of engineering at BP, to discuss how engineering can deliver new breakthroughs in the transition to clean energy.

McKinsey: What industry-wide changes will be required to enable the energy transition needed to meet net-zero targets, and how is BP responding?

Aleida Rios: If the world is going to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, we need everyone to play a role. I think it’s brilliant that companies like Ørsted and Tesla are pure play and renewable, but I think it’s even more important that companies—like BP—which are not yet fully green but are “greening,” have credible plans to transition to lower carbon.

In 2020, BP called for reimagining energy for people and our planet, and we launched a new strategy that will help BP pivot from an international oil company focused on producing resources to an integrated energy company focused on delivering solutions for customers. Across the industry, companies like ours need to put together plans to get to net zero to help meet the Paris climate goals. In our case, we set an ambition to be net zero by 2050 or sooner and to help the world get to net zero, supported by ten aims.

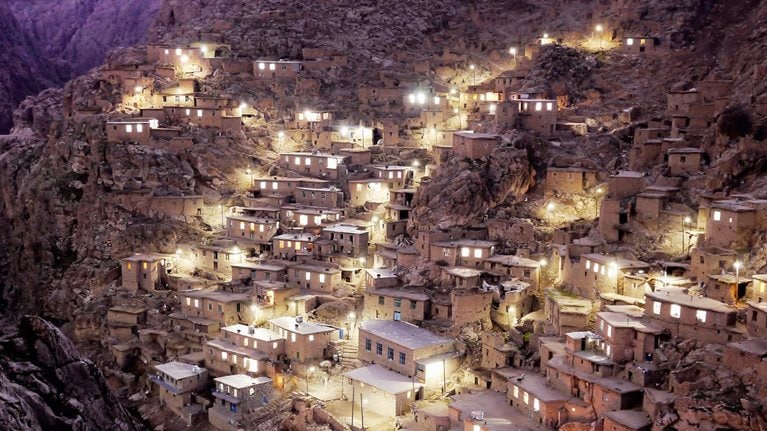

We are no longer going to be predominantly a hydrocarbon company. Instead, we are going to have a balanced portfolio with resilient hydrocarbons, convenience and mobility, and low carbon. I spend most of my time helping to ensure we have a resilient hydrocarbon offer to many parts of the world alongside our work to scale low-carbon energy with offshore wind. As a recent example, we now have an offshore wind pipeline of 5.2 gigawatts [GW]. We’ve essentially gone from nothing to 5.2 GW—and we’ve just announced that we have 24.5 GW in the development portfolio for our renewables. We will have that balanced portfolio and those capabilities to enable an integrated-energy system, which is necessary to enable the world to transition.

McKinsey: How will the engineering discipline need to evolve to deliver new energy solutions as the oil and gas industry transitions?

Aleida Rios: Our industry needs entirely new ways of working. We need to take new ideas and incubate and scale them much faster than we’ve ever done before. Engineers play that critical role of making an idea into something that can be scaled. I think we need to put a greater emphasis on being able to transfer skills that we had in the hydrocarbon business over to the new energy areas very quickly.

Part of the scale problem is that solutions need to be packaged in a way that brings down costs significantly from where they are today. That’s why competition is important. It can help bring down costs so that businesses will have the incentive to develop the infrastructure needed for achieving net zero.

Finally, we need talent to actually develop these new technologies. We see such talent in solar and wind—so we know it’s possible. There needs to be a system that allows people to work on technology but also incentivizes the green premium to keep coming down. Hydrogen is a perfect example. The technology is readily available, but the premium is too high, and therefore, we need to create the demand.

McKinsey: What breakthroughs in engineering have you seen that inspire you about the future?

Aleida Rios: Engineering is built on breakthroughs. I became an engineer because I was inspired by breakthroughs. I grew up in Houston, Texas, the energy capital of the world and where NASA was putting people on the moon.

In How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, Bill Gates says, “My basic assumption about climate change comes from a belief in innovation. The conditions have never been more clear for backing energy breakthroughs. It’s the power to innovate that makes me hopeful.”

I am hopeful as well. Significant engineering challenges have been overcome in the past ten years. I remember talking about the challenges of solar and wind, and the solutions seemed like they were decades away. Now we have commercially viable solutions, driven by that innovation approach and putting engineering at the heart of those solutions.

Deploying this innovation is about creating the right conditions to back these technologies and decarbonization—and investing in the right resources. If you look at the cost of onshore wind and solar, we’ve lowered the costs by almost 50 percent on wind and almost 90 percent on solar since 2005. And I think most of the breakthroughs came in the past ten years rather than the initial ten years.

Voices on Infrastructure: Reimagining engineering and project development to meet net-zero targets

McKinsey: What new partnerships and contracting approaches could improve outcomes?

Aleida Rios: I think we need to move much faster on partnerships in areas that require more innovation. As an example, in 2021, we formed a partnership with CEMEX to work to enable full abatement in the cement sector. And we’re leading the Net Zero Teesside Power and Northern Endurance Partnership projects, which we hope will enable the first net-zero industrial cluster in the United Kingdom.

Another example of faster-moving experimentation is BP Launchpad, which enables us to partner with and apply our capabilities to new areas, as well as to identify key capabilities that we need in our own assets. Launchpad is obviously an innovation engine and entrepreneurship, but it’s early-stage innovation, and getting those early-stage innovations, that R&D, across the finish line is important for getting to net zero.

If we only focus on continuous improvement and easy wins, we won’t achieve net zero. It’s going to require doubling down on the harder areas, the right projects, and the right relationships. I’m not afraid that the technology won’t be there. It’s the other pieces—the mindset, the ways of working, the partnerships—that we need to enable net zero.

McKinsey: What competitive-advantage opportunities exist for first-mover engineering-driven companies?

Aleida Rios: I’ve talked a lot about behaviors and partnerships and mindsets, but at the end of the day, it’s a physical problem, and these technologies will provide a huge economic opportunity for first movers.

Being a first mover allows you to build capability by doing. We need to make sure that what we’re doing isn’t just partnering with others to provide resources in terms of investment and capital. It’s also a learning opportunity. We’ve got to make sure that we’re providing the know-how.

We’re an incumbent in the energy sector, and we have significant capabilities that we’re going to be able to leverage. For example, our deepwater know-how is a first-mover advantage on offshore wind. It gives me a lot of hope because we now have the capability and technologies to enable it.

McKinsey: How does an organization attract, develop, and retain the talent required to meet net-zero targets?

Aleida Rios: We need to diversify and create transferable skills. A good example of that is our effort to diversify the career road maps for engineers so that they can apply their skills in a different way. In fact, we just transitioned 50 percent of our subsea-riser engineers to becoming CCUS [carbon capture, utilization, and storage] technology managers in Net Zero Teesside.

The opportunities to retain and attract talent are huge—every engineer I’ve talked to wants to help resolve the climate challenge and sees engineering as core to doing so. We need to be able to create a vision for how they can transfer their skills to these new areas.

It’s also important to offer a diverse and inclusive environment for people to do their best. We do this through our actions, not just our strategy. We do it through what we enable and our purpose. On this point, we recently announced our ambition to reach gender parity in our top team (the top 120 roles) by 2025. By 2030, we aim to have women in at least 40 percent of all roles at every level of our company.

McKinsey: Why is gender equity good for business in engineering?

Aleida Rios: It’s no secret that I’m passionate about diversity. Diverse teams create more value and innovation. I’m especially inspired by our young engineers because they want to be part of solving the problem. A lot of times they don’t see a traditional oil and gas company as part of that, and I think the more we work to represent everyone, the more innovation we’ll get.

Just last year, I helped create the One BP Early Careers Engineering Program, and our initial Early Careers Engineers cadre is hugely diverse—it’s 44 percent women. That’s our future. I deeply believe in our purpose to reimagine energy for people and our planet, and that needs to include everyone. My leadership team of direct reports, the chief engineers, is 40 percent female. I want to see that percolate all the way down.

I was recently inspired to see that over 50 percent—six out of 11 people of our executive team—are women, which is almost unheard of, not just for an oil and gas company but for any company. It was a proud moment, and it was a strategy in action.

This article is part of Global Infrastructure Initiative’s Voices on Infrastructure.

Comments and opinions expressed by interviewees are their own and do not represent or reflect the opinions, policies, or positions of McKinsey & Company or have its endorsement.