| DELIVERING ON DIVERSITY, GENDER EQUALITY, AND INCLUSION

|

| Click to get this newsletter weekly |

|

|

| In this issue, we look at a new commitment by the Carlyle Group, an effort by top banks to expand credit access in the US, and why Americans are hearing so much about lead lately. |

|

|

| • |

Upping the ante. Last week, the private-equity firm the Carlyle Group announced that it will link the compensation of its CEO, Kewsong Lee, to the firm’s performance when it comes to hiring diverse candidates, fostering an inclusive culture, and diversifying its portfolio companies’ boards. Carlyle employees’ performance bonuses will also hinge on whether they meet individual diversity objectives. Women and people of color made up nearly two-thirds of the firm’s US hires last year, and Carlyle reports that women manage more than half of its $260 billion in assets under management. That’s a rarity in the industry; women make up just one in five private-equity employees worldwide, and they hold less than 12 percent of senior roles. In the United States, McKinsey research shows, Black professionals make up only 1 to 2 percent of investment-deal teams. At the same time, private-equity firms have an outsize ability to shape the status quo of business; they back nearly 20,000 companies in North America alone. Tackling gender and racial inequities at firms and their portfolio companies—including on those companies’ management teams—could change the face of business. |

|

|

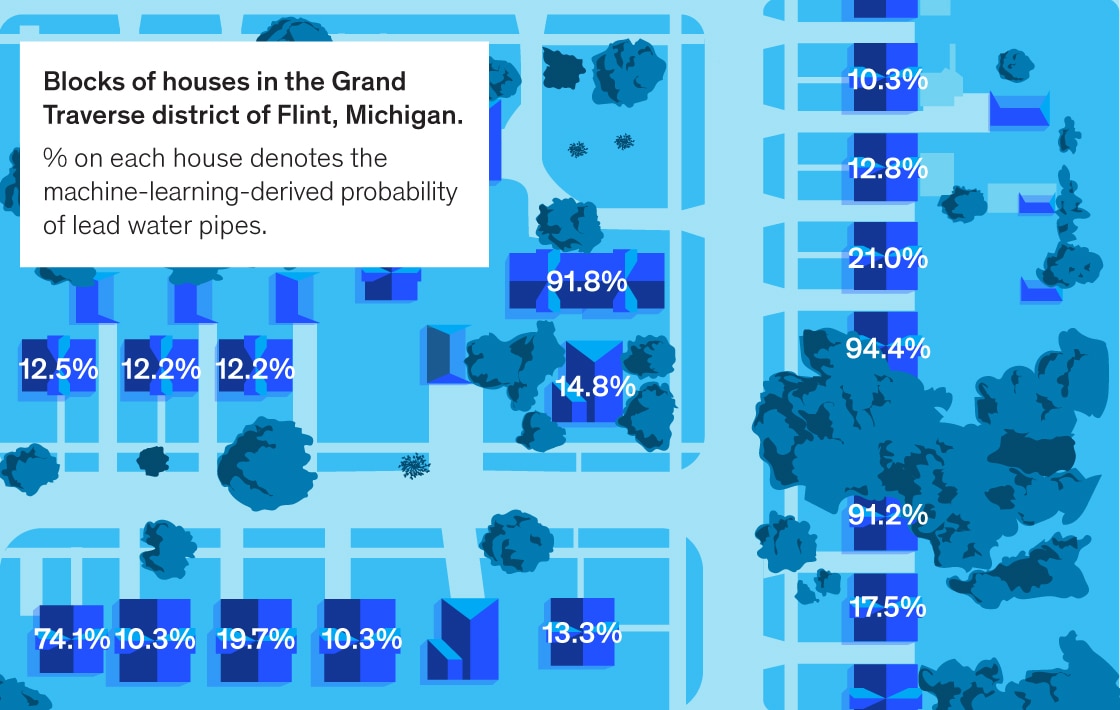

Much of America’s infrastructure is outdated or in disrepair, and water and sewer systems are no exception. An estimated six to ten million homes in the United States receive drinking water through lead pipes and service lines, which means that many Americans are ingesting this powerful neurotoxin. Complicating the matter is the fact that utilities don’t know where all of the lead pipes and service lines are. Finding and replacing these lines will be extremely costly, but it could yield billions in future benefits. This is also an issue of equity, given that lead exposure is particularly high among Black children and those from low-income families. A few cities, including Lansing, Michigan, and Madison, Wisconsin, have already gotten rid of all their lead service lines. Others—including Flint, Michigan—are on their way there. One tool that’s helping tackle the issue in Flint and beyond: machine learning. A statistical model built by a team from the University of Michigan can accurately predict which service lines are made of lead. (If you asked the model to distinguish between two homes in Flint—one with a lead service line, one randomly chosen—the model would be right 94 percent of the time.) That’s one way AI can be used for good. |

|

|

| — Edited by Julia Arnous, an editor in McKinsey’s Boston office |

|

| Click to subscribe to this weekly newsletter |

|

|

Did you enjoy this newsletter? Forward it to colleagues and friends so they can subscribe too.

Was this issue forwarded to you? Sign up for it and sample our 40+ other free email subscriptions here.

|

|

|

Copyright © 2021 | McKinsey & Company, 3 World Trade Center, 175 Greenwich Street, New York, NY 10007

|

|

|