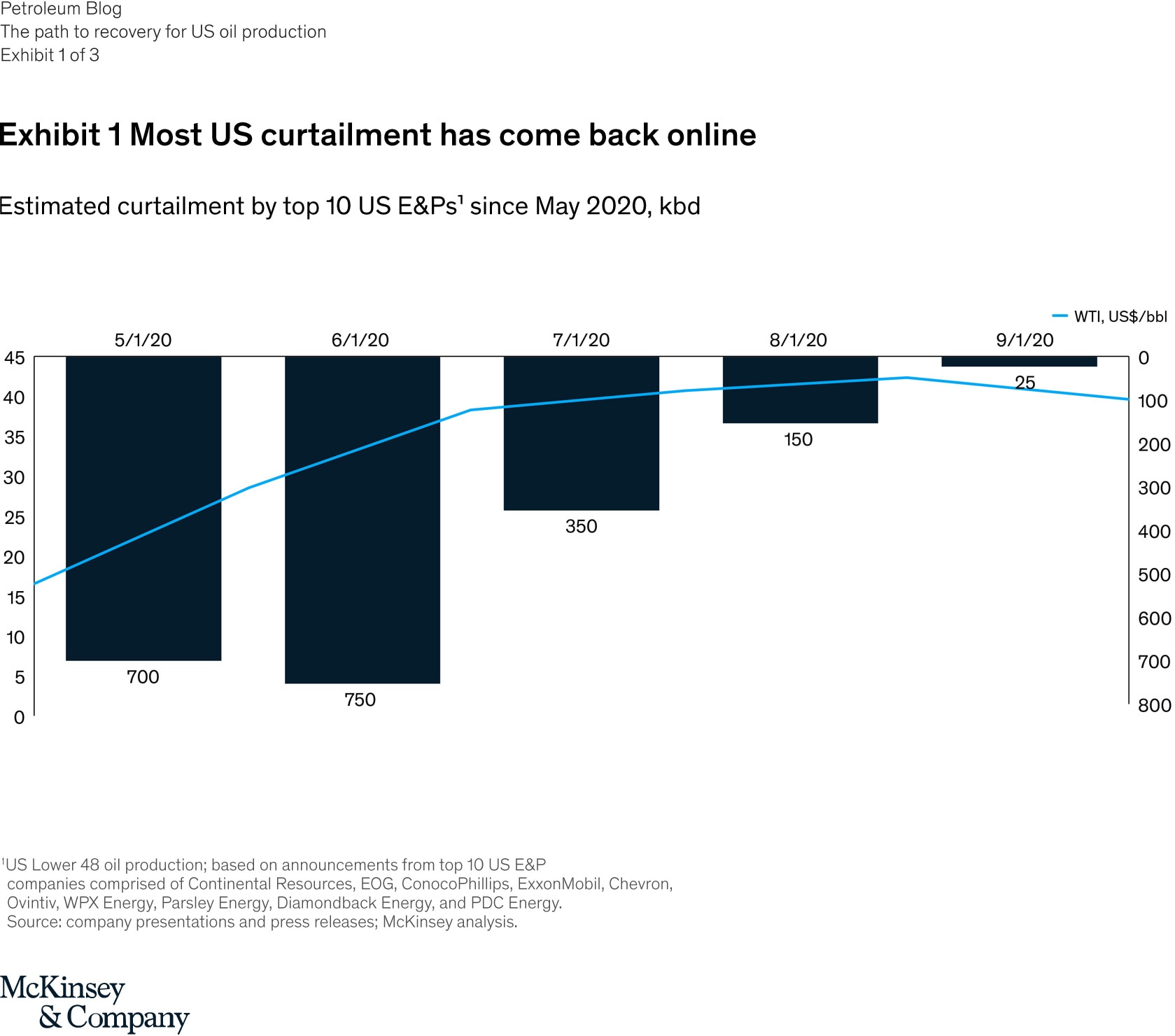

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered an unprecedented fall in global oil demand of some 20–25 mbd, or roughly 20 percent. Faced with considerable oversupply and collapsing prices, US operators moved quickly to reduce drilling activity and shut in production from active assets, reducing their oil output by about 2.3 mbd. By June 2020, the top 10 US exploration and production (E&P) operators had shut in 0.8 mbd of production in the US Lower 48 states—representing between 50 and 60 percent of total onshore US curtailment—as well as reducing their capex programs by 30 to 50 percent. However, as prices began to recover and stabilize at around $40 per barrel for WTI, operators started bringing curtailed production back online, a process that should be completed by October 2020 (Exhibit 1).1

Examples from the Permian basin

The return of curtailed production represents what we see as the first phase in a three-phase recovery that is based on well economics. Taking the Permian basin as an example for pricing purposes, the phases are:

- Phase 1: Returning shut-in production requires only the cash cost of operation and dispatch, and has a breakeven price of $12 to $20 per barrel.2 This phase has largely been completed.

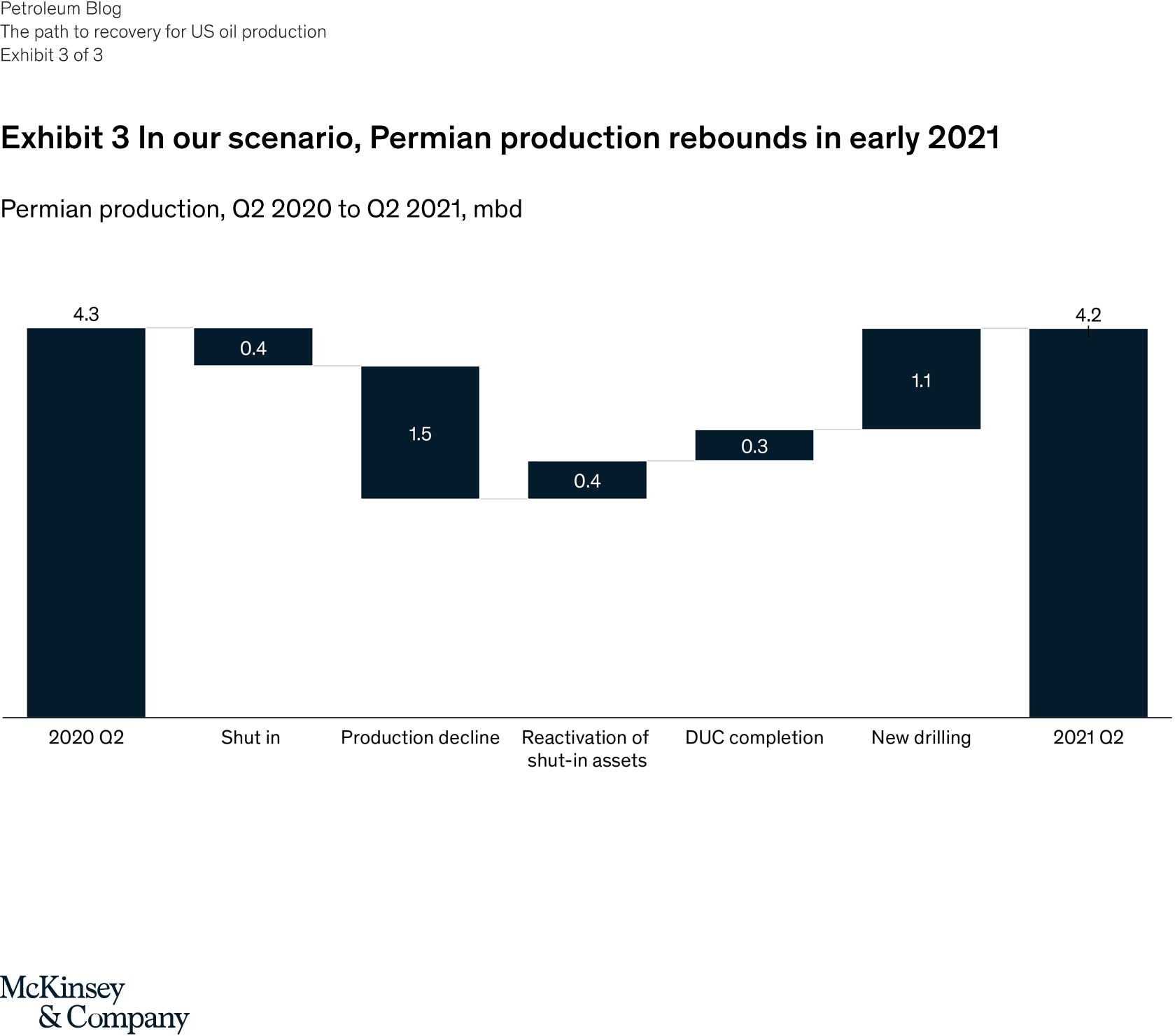

- Phase 2: Activating drilled but uncompleted (DUC) inventory is less costly than new drilling, as 30 to 40 percent of drilling and completion costs have already been incurred, resulting in a breakeven price of $25 to $35 per barrel. We expect activating DUC inventory to contribute 0.3 mbd through 2021.

- Phase 3: Drilling new wells is the most costly option, with a breakeven price of $30 to $45 per barrel, and is likely to be pursued only after shut-in production has been returned and the DUC inventory has returned to historical levels. Drilling new wells is expected to contribute a further 1.1 mbd of production through 2021.

The progression from phase 1 to phase 3 is sensitive to the behavior of individual operators, and depends partly on the level of DUC inventory they decide to maintain.

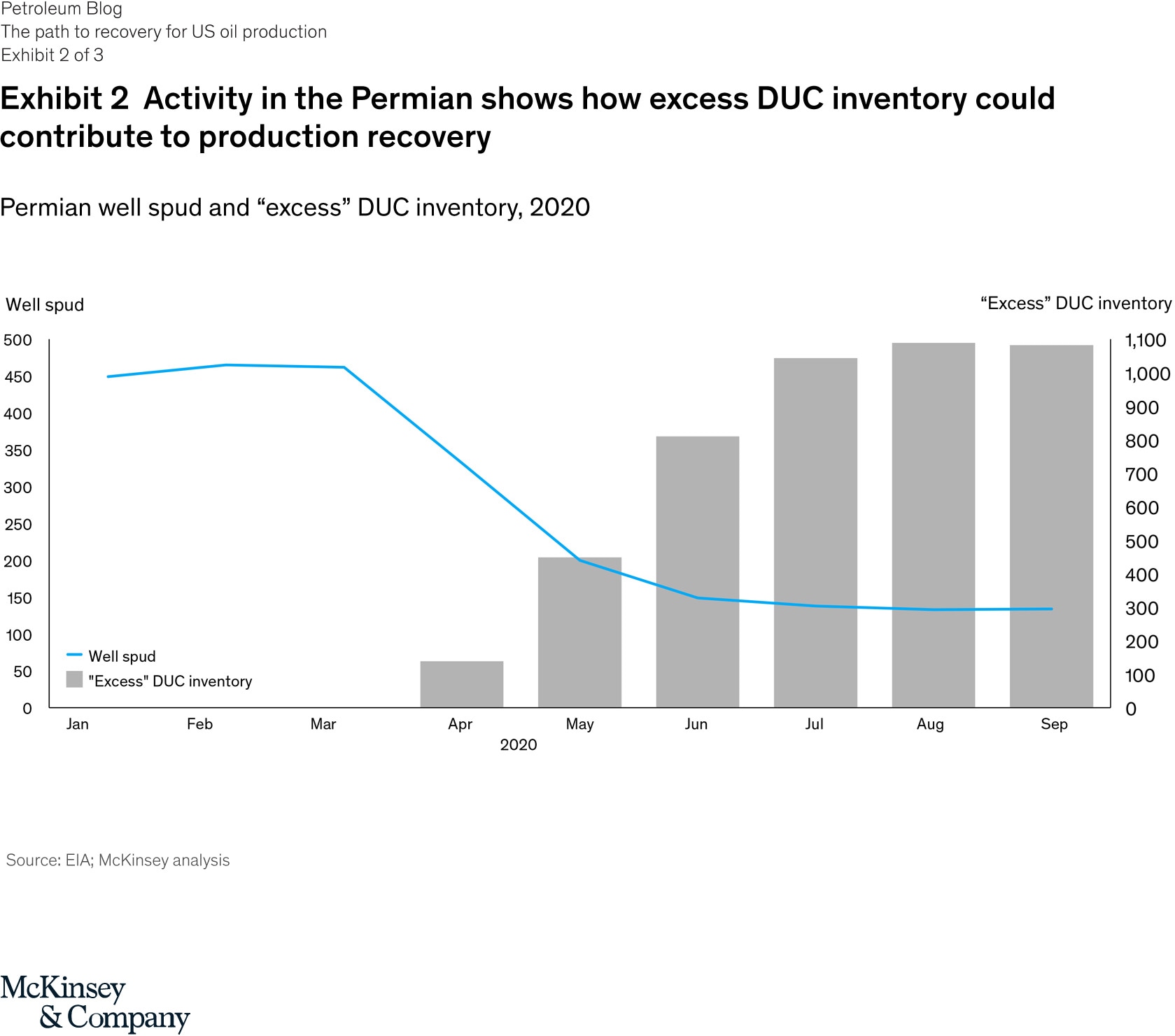

Permian drilling activity fell sharply from a peak of 449 wells in January to a low of 134 wells in September, although numbers have been stabilizing since June. Meanwhile, completion activity decreased from 438 wells in January to 98 wells in July. Since well completion lags well spud by 3.5 months on average, this reduction in activity has led to an increase in the working inventory of DUCs, reaching an “excess” of roughly 1,100 wells over the normal level.3 As completion trends began to increase with 155 wells in August, the spud rate remained flat, indicating that the pool of DUC wells is beginning to be consumed (Exhibit 2).

On the assumption that Permian completion rates gradually return to 60–80 percent of pre-pandemic levels, reducing the excess DUC inventory would take 16 months and cover about 1,000 wells. Some 800 of these are expected to be completed by mid-2021, contributing 0.3–0.4 mbd to Permian production. We expect the inventory overhang to act as a minor, if persistent, headwind to new drilling activity until normal inventory levels are restored by the end of 2021.

Under this scenario, new drilling activity rebounds during the first quarter of 2021, with some 2,300 new wells producing 1.1 mbd and offsetting most of the decline by the second quarter (Exhibit 3).

What next?

As demand and prices gradually recover, the industry faces new questions.

- How will reductions in headcount and COVID-compliant workplace safety requirements affect the timeline for well completions? Will activity be slowed by a backlog in demand?

- How will operators’ decisions on DUC inventory levels affect the timing of new drilling?

- Have shut-ins resulted in any degradation of assets (e.g., proppant softening) that could accelerate declines or reduce recoverable reserves?

- Will the slow return to new drilling activity result in decreased rig supply in the market or consolidation among drillers?

- How will today’s DUC inventories affect the transition from phase 2 to phase 3 of recovery?

- How will E&P and service companies respond to continuing disruption in the supply chain and personnel? Will they have sufficient resources available when demand returns?

By the second quarter of 2021, we expect US Lower 48 onshore production to rebound to roughly 80 percent of pre-pandemic levels, from a low of 7.9 mbd to 8.7 mbd.4 About a quarter of the incremental production is expected to come from the completion of excess DUC inventory, and the remainder from new drilling activity. However, global oil demand is not expected to recover fully until 2024–26.

1 The cash costs and breakeven prices shown here are estimates based on production in Permian Delaware, and assume that 30–40 percent of capex is allocated to drilling. Prices and priorities may vary by basin. Permian producers hedged 50 percent of their 2020 oil production at $45 per barrel, so they are unlikely to shut in more than the remaining unprotected 50 percent of output.

2 The “excess” DUC volume was calculated as the difference between actual completions and the number of completions that would have been expected from drilling activity 3.5 months earlier.

3 This expectation is based on the “OPEC+ control restored” scenario developed by McKinsey Energy Insights, which assumes that the oil price remains at $40–$50 per barrel through 2021, OPEC+ continues to manage output to balance the market, the drop in demand in 2020 is limited to 8.3 mbd, and demand recovers to 2019 levels by 2022. For more details, see Joana Candina, David González Fernández, Stephen Hall, and Francesco Verre, “Reinventing upstream oil and gas operations after the COVID-19 crisis,” McKinsey & Company, August 20, 2020.

4 This expectation is based on the “OPEC+ control restored” scenario developed by McKinsey Energy Insights, which assumes that the oil price remains at $40–$50 per barrel through 2021, OPEC+ continues to manage output to balance the market, the drop in demand in 2020 is limited to 8.3 mbd, and demand recovers to 2019 levels by 2022. For more details, see Joana Candina, David González Fernández, Stephen Hall, and Francesco Verre, “Reinventing upstream oil and gas operations after the COVID-19 crisis,” McKinsey & Company, August 20, 2020.