For survivors of modern slavery, the end of the nightmare is hardly the end of the story. After rescue or escape, the recovery process begins.

That process can be long and complicated, and it’s often aided by anti-slavery organizations. Not long ago, one of them, who has worked alongside local authorities to rescue over 53,000 survivors from violence and oppression, recognized an opportunity to improve its global recovery programs. As the NGO developed a 10-year plan to scale the number of people it serves by 20 times, it approached Noble Intelligence—a group of data and analytics experts from McKinsey Analytics that uses advanced technologies and AI to help address social and humanitarian crises—to understand the best ways to help survivors recover and reintegrate into society.

McKinsey partner Gaurav Batra helped lead the pro bono engagement. “The client had an ambitious plan to support a million people by 2030, up from 53,000 now,” he says. “And when it came to helping them improve the effectiveness of their programs, we collectively knew data would play a key role.”

But the information the organization had wasn’t ideal. Across the client’s field offices, while there was a set of organizational best-practices for managing the recovery process, there were on the ground challenges to uniformly collect the data. This challenge did not, however, mean the client didn’t collect data at all. On the contrary, there was tons of it.

“We had information on about 10,000 different cases,” says McKinsey expert associate partner Ashley van Heteren. “That worked out to some 250,000 data points and over 100,000 paragraphs of blinded notes from caseworkers.”

Conventional means of sifting through that much material, all of which was completely anonymized and stored on encrypted software, would be virtually impossible. So, the team turned to artificial intelligence, a technology that has broad applications for humanitarian relief that’s being applied in the race for a cure for COVID-19 and in triage for hospitals. “Machine learning could help us understand which services, deployed at which points in recovery, would be most impactful,” Ashley explains.

According to Gaurav, the analysis required extreme attention to detail and a quality that’s perhaps perceived to be at odds with data: empathy. “Analytics can feel impersonal,” he says, “especially if the colleagues working on it are located away from the client’s offices and the larger team. This was long before the COVID-19 outbreak, so we made sure everyone on this project was co-located from start to finish, which made communication easier and drove home the gravity of the work for everyone.”

The weight of that responsibility was significant. While analytics was an enormous part of the project, the team never lost sight of the lives at the center of their work. “The hallways in our client site were lined with photos of survivors,” engagement manager Andrea Grass recalls. “We saw them every day on the way to our team room. Their stories were very real reminders of the importance and urgency of the work.”

In light of this, one choice the team made early on was that they would not recommend removing any existing services the NGO already offered. “We decided that the possibility of a ‘false negative’—a service that some survivors did not like but that is ultimately helpful—was high enough that we might risk removing something valuable,” Ashley explains.

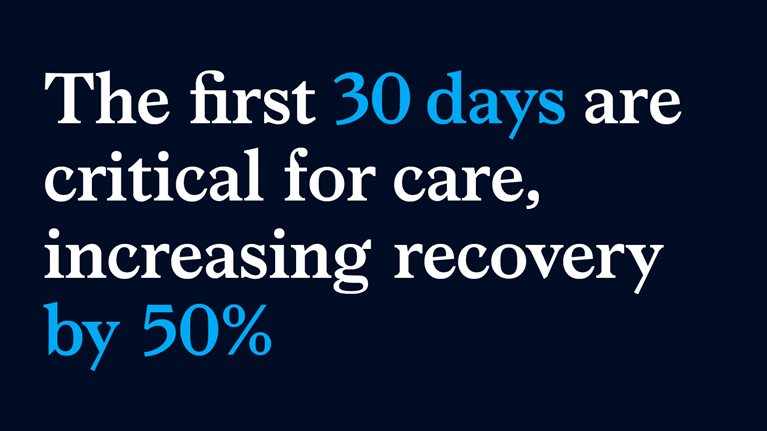

Through their research and a 24-hour insight-gathering session with dozens of data scientists around the world, the team helped the client organization gain new insights. For one, timing of case workers’ intervention was even more important in a survivor’s recovery than the NGO realized. “We found that the first 30 days are the most critical,” Gaurav explains. According to the team’s model, if a survivor receives care within that timeframe, they are 50 percent more likely to succeed in their recovery.

Elsewhere, natural-language processing and sentiment analysis of caseworker notes revealed that group-oriented services were received positively by survivors, while parts of the process related to their case investigation were regarded negatively. This inspired the organization to seek further investment in programs that foster a sense of community: support meetings and buddy systems to strengthen bonds among survivors.

According to the client, findings like these have the potential to help survivors increase the speed of recovery by anywhere from 20 to 100 percent, reducing the average recovery period by up to 14 months. In fact, the work has been so promising that the client has already invested in its own analytics team that is capable of stewarding the work that we began together with them.

“It was inspiring to partner with an organization like this and see how technology might help them in their mission,” says Ashley. “Analytics and AI are well known for the way they can help organizations make better decisions. In this project, we got to see how those technologies can also give people hope.”