Two-thirds of US public and private companies still admit that they have no formal CEO succession plan in place, according to a survey conducted by the National Association of Corporate Directors last year.1 And only one-third of the executives who told headhunter Korn Ferry this year that their companies do have such a program were satisfied with the outcome. These figures are alarming. CEO succession planning is a critical process that many companies either neglect or get wrong. While choosing a CEO is unambiguously the board’s responsibility, the incumbent CEO has a critical leadership role to play in preparing and developing candidates—just as any manager worth his or her salt will worry about grooming a successor.

An ongoing process

Many companies treat the CEO succession as a one-off event triggered by the abrupt departure of the old CEO rather than a structured process. The succession is therefore often reactive, divorced from the wider system of leadership development and talent management. This approach has significant risks: potentially good candidates may not have sufficient time or encouragement to work on areas for improvement, unpolished talent could be overlooked, and companies may gain a damaging reputation for not developing their management ranks.

Ideally, succession planning should be a multiyear structured process tied to leadership development. The CEO succession then becomes the result of initiatives that actively develop potential candidates. For instance, the chairman of one Asian company appointed three potential CEOs to the position of co-chief operating officer, rotating them over a two-year period through key leadership roles in sales, operations, and R&D. One of the three subsequently dropped out, leaving two in competition for the top post.

Rotation is a great way to create stretch moments exposing candidates to exceptional learning opportunities. However, rotation is not enough in itself. A leadership-succession process should be a tailored combination of on-the-job stretch assignments along with coaching, mentoring, and other regular leadership-development initiatives. Companies that take this approach draw up a development plan for each candidate and feed it into the annual talent-management review, providing opportunities for supportive and constructive feedback. In effect, the selection of the new chief executive is the final step in a carefully constructed and individually tailored leadership-development plan for CEO candidates.

Looking to the future

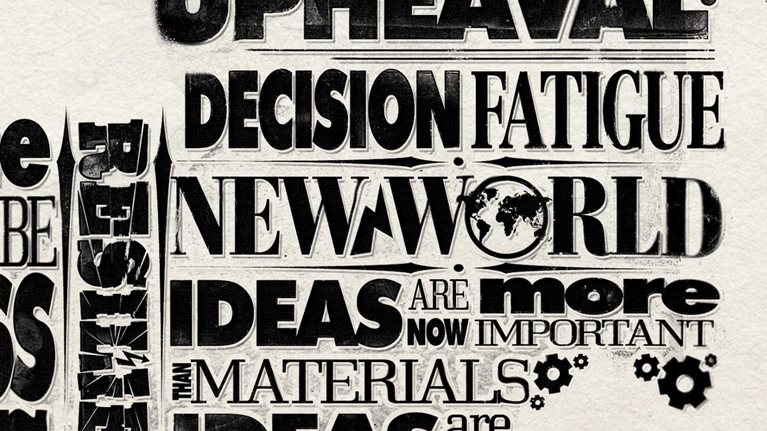

Too often, companies forget to shape their candidate-selection criteria in the light of their future strategic direction or the organizational context. Many focus on selecting a supposedly ideal CEO rather than asking themselves what may be the right CEO profile given their priorities in the years ahead. The succession-planning process should therefore focus on the market and competitive context the new CEO will confront after appointment. One Latin American construction company, for example, began by conducting a strategy review of each business in its portfolio. Only when that had been completed did it create a CEO job profile, using the output of the review to determine who was best suited to deliver the strategy.

More broadly, three clusters of criteria can help companies evaluate potential candidates: know-how, such as technical knowledge and industry experience; leadership skills, such as the ability to execute strategies, manage change, or inspire others; and personal attributes, such as personality traits and values. These criteria should be tailored to the strategic, industry, and organizational requirements of the business on, say, a five- to eight-year view. Mandates for CEOs change with the times and the teams they work with. The evaluation criteria should change, as well. For example, the leadership style of a CEO in a media business emphasized a robust approach to cost cutting and firefighting through the economic crisis. His successor faced a significantly different situation requiring very different skills, since profitability was up and a changed economic context demanded a compelling vision for sustained growth. When industries and organizations are in flux and a fresh perspective seems like it could be valuable, it’s often important to complement the internal-candidate pipeline with external candidates.

Much as the needs of a business change over time, so do the qualities required of internal candidates as a company’s development programs take effect. It’s therefore vital to update, compare, and contrast the profiles of candidates against the relevant criteria regularly. This isn’t a hard science, of course, but without rigor and tracking it is easy to overlook. For example, the picture painted by the exhibit might stimulate a rich discussion about the importance to the evolving business of these candidates’ natural strengths and weaknesses, as well as the progress they are making to improve them. Other candidates may be evolving different profiles. Regularly reviewing these changes helps companies ensure that the succession process is sufficiently forward looking.

Debiasing succession

Many biases routinely creep into CEO-succession planning, and their outcome is the appointment of a specific individual. As we well know, decision making is biased. Three biases seem most prevalent in the context of CEO succession. CEOs afflicted by the MOM (“more of me”) bias look for or try to develop a copy of themselves. Incumbents under the influence of the sabotage bias consciously or unconsciously undermine the process by promoting a candidate who may not be ready for the top job (or is otherwise weak) and therefore seems likely to prolong the current CEO’s reign.2 The herding bias comes into play when the members of the committee in charge of the process consciously or unconsciously adjust their views to those of the incumbent CEO or the chairman of the board.

Would you like to learn more about our People & Organizational Performance Practice?

Contrary to what you might conclude from all this, the lead in developing (though not selecting) the next leader should be taken by the current CEO, not by the board, the remuneration committee, or external experts. The incumbent’s powerful understanding of the company’s strategy and its implications for the mandate of the successor (what stakeholder expectations to manage, as well as what to deliver, when, and to what standard) creates a unique role for him or her in developing that successor. This approach encourages the CEO to think about the longer term and to “reverse engineer” a plan to create a legacy by acting as a steward for the next generation.

That said, companies must work hard to filter out bias and depersonalize the process by institutionalizing it. A task force (comprising, perhaps, the CEO, the head of HR, and selected board members) should regularly review the criteria for selecting internal candidates, assess or reassess short-listed ones, provide feedback to them, and develop and implement a plan for their development needs. The task force should identify the right evaluation criteria in advance rather than fit them to the pool of available candidates and should ensure that its members rate candidates anonymously and independently. The resulting assessment ought to be the sum of these individual assessments. Relatively few companies use such a task force, according to a 2012 Conference Board survey on CEO succession.

Board governance

A collection of insights for corporate boards, CEOs, and executives to help improve board effectiveness including: board composition and diversity, board processes, board strategy, talent and risk management, sustainability, and purpose.

One in three CEO successions fails. A forward-looking, multiyear planning process that involves the incumbent CEO would increase the odds of success.