. . . chance favors only the prepared mind.

Senior executives generally agree that crafting strategy is one of the most important parts of their job. As a result, most companies invest significant time and effort in a formal, annual strategic-planning process that typically culminates in a series of business unit and corporate strategy reviews with the CEO and the top management team. Yet the extraordinary reality is that few executives think this time-consuming process pays off, and many CEOs complain that their strategic-planning process yields few new ideas and is often fraught with politics.

Why the mismatch between effort and result? Evidence we culled from research on the planning processes at 30 companies (see sidebar, "About the research") and work with more than 50 additional companies points to a common dispiriting explanation: the annual strategy review frequently amounts to little more than a stage on which business unit leaders present warmed-over updates of last year's presentations, take few risks in broaching new ideas, and strive above all to avoid embarrassment. Rather than preparing executives to face the strategic uncertainties ahead or serving as the focal point for creative thinking about a company's vision and direction, the planning process "is like some primitive tribal ritual," one executive told us. "There is a lot of dancing, waving of feathers, and beating of drums. No one is exactly sure why we do it, but there is an almost mystical hope that something good will come out of it."

But something good ought to come out of it. In a business environment of heightened risk and uncertainty, developing effective strategies is crucial. But how can companies reform the process in order to get the payoff they need?

New goals for strategic planning

Part of the answer lies in taking a fresh look at the substance of business unit and corporate strategy. But a more important—and often overlooked—element is to rethink the process by which strategy is made. It can even be argued that without a strong process, it is unlikely that the substance will come out right.

A key starting point is the acceptance of the counterintuitive notion that the strategic-planning process should not be designed to make strategy. Henry Mintzberg, a professor of management at McGill University, calls the phrase "strategic planning" an oxymoron.1 He argues that real strategies are rarely made in paneled conference rooms but are more likely to be cooked up informally and often in real time—in hallway conversations, casual working groups, or quiet moments of reflection on long airplane flights.

What then is the purpose, if any, of a formal planning process? Our research persuades us that the exercise can add value if it has two overarching goals. The first is to build "prepared minds"—that is, to make sure that decision makers have a solid understanding of the business, its strategy, and the assumptions behind that strategy, thereby making it possible for executives to respond swiftly to challenges and opportunities as they occur in real time. GE Capital, for instance, has consistently proved quicker to react and better able to value acquisition opportunities than have its competitors. Part of this success is due to a strategy process ensuring that GE Capital's executives have a strong grasp of the strategic context they operate in before the unpredictable but inevitable twists and turns of their business push them to make M&A and other critical decisions in real time.

The second goal is to increase the innovativeness of a company's strategies. No strategy process can guarantee brilliant flashes of creative insight, but much can be done to increase the odds that they will occur. In addition to formal planning at the business unit level, for example, Johnson & Johnson uses crosscutting initiatives on major issues such as biotechnology, the restructuring of the health care industry, and globalization in order to challenge assumptions and open up the organization to new thinking.

In our research, we didn't find a single company that was best at achieving both of these goals, although GE came closest. Instead, companies tended to be better either at the formal process of creating prepared minds or at the more informal process of driving strategic creativity. In addition, we found that some practices of companies in the sample were very specific to their industry or culture. What we will describe is thus not a single company's best-practice process but a composite picture, drawing ideas from a number of companies and focusing on what we have found to be the most transferable ideas.

Preparing minds

Most companies have an annual cycle of strategic-planning reviews that typically culminate in a presentation to the board. While the process itself might be quite formal, at its heart it is just a series of meetings. The trick is to transform them from the "dog-and-pony shows" that many companies now experience into true conversations that prepare the minds of the executive team for real-time strategy making in the year ahead. We have found that the key to designing effective strategy conversations is getting a number of critical details right.

Start with a commonsense approach about who should attend. Real conversations take place not in large groups but in small gatherings of no more than ten. Attendees at strategy reviews should thus be strictly limited to the principal strategic decision makers—the CEO and the head of the unit, along with the group or sector head, the chief financial officer, one or two of the unit's crucial managers, and the head of corporate strategy. The exact list will differ from company to company. More executives will fight to be involved, but they can be kept "in the loop" through other forums.

Resign yourself to the fact that in-depth discussions of strategy take time. Calendar-challenged executives may chafe, but most CEOs we interviewed claimed that they want to spend about a third of their time on strategy. That amounts to 80 days in a 240-working-day year. Against that backdrop, it doesn't seem unreasonable to spend 20 to 30 days (that is, 15 to 25 days for business units, plus 2 to 5 days for sector and corporate strategy) in intensive, well-prepared discussions of strategy.

The venue should, if possible, be the site of the business unit; the CEO will get a better feeling for what is going on there, and the spirit of the session will be less "a summons from headquarters" and more a true discussion.

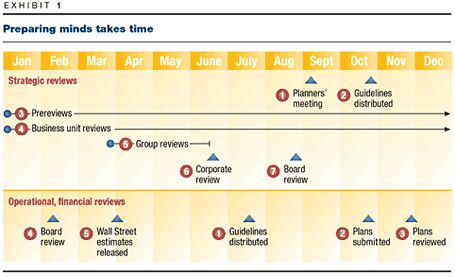

Above all, companies should avoid combining strategy reviews with discussions of budgets and financial targets, because when the two are considered together, short-term financial issues dominate at the expense of long-term strategic ones. As an executive put it, "If they haven't already talked about the numbers, they're gonna talk about the numbers." Thus, the best-practice companies we surveyed organized two clearly demarcated meetings: a full day on strategy with each business unit and a shorter meeting, at a different time of year, to set financial targets. The two are then coupled in a rolling annual cycle; the financial plan is an input for the strategy discussion, which in turn is an input for the next financial plan (Exhibit 1 shows a sample calendar).

It was very clear, among the best-practice companies we studied, that those who carry out strategy must also make it. Business unit heads can be supported by staff and consultants but cannot outsource strategy making to them. On the contrary, the heads of business units and other key line executives must personally invest their time in developing strategy and preparing for the review.

A common question is how much guidance the corporate center should give the business units in preparing for these meetings. The answer is, "enough but not too much." Insist on a few basics, such as an analysis of customers, competitors, and economics. At the same time, every business unit should be given plenty of latitude, for two reasons. First, each is different, and simply asking all of the business units to fill out the same strategy template is likely to obscure more than it reveals. Second, strategy reviews are a great way for the CEO to check the quality of the management team, and excessive corporate guidance makes it hard to tell the real strategists from those who are merely good at filling out templates.

The run-up to the review meeting is important. Many companies put the business units through dress-rehearsal preview meetings with the sector head and the head of strategy to ensure that they are ready. It is also essential to send out documents at least a week before the meeting so that time isn't wasted simply flipping through slides. The CEO and corporate executives, in turn, have an obligation to read the documents before the meeting and thus to come ready to dive into the key issues.

Culture and tone in the reviews are critical. A variety of approaches can work, ranging from the in-your-face culture of Emerson—where Chuck Knight, the CEO for 27 years, led reviews that were legendary for their intensity and even combative tone—to the more formal, consensus-oriented style of BP. But some cultures are definitely wrong. In the most common misstep, the business units see the reviews as interference from headquarters and try to reveal as little as possible. The corporate team responds by playing "gotcha," trying to pull out the skeletons hidden in the business units' closets. Instead, all of the people at the meeting should feel that they are sitting on the same side of the table, confronting common challenges.

Disciplined follow-up is essential. Collect the notes of the meeting, send them to participants, and connect its outcome to other critical corporate processes. Near-term financial goals should be linked with the strategy's long-term financial implications, for example, and talent requirements with human-resources reviews. Management compensation should be tied to success in achieving strategic goals.

Encouraging creative minds

For the type of formal strategy review described above, success isn't measured by the number of breakthrough ideas it produces. Rather, success is more modestly measured by how well the review helps management forge a common understanding of its environment, challenges, opportunities, and economics, thus laying the groundwork for better real-time strategic decision making going forward. Unfortunately, our research showed that even when such calendar-driven processes are done well, they tend to produce "in-the-box" strategies. The calendar-driven process is necessary but not sufficient, and additional actions are needed to spur strategic creativity.

As one of the world's leading experts on creativity, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, of Claremont Graduate University, has argued, creative thinking cannot be forced.2 Companies can, however, create conditions in which creative accidents are more likely to happen. Through our research, we identified two mechanisms by which companies increase the odds of promoting creative accidents in strategy: encouraging bottom-up experiments and driving top-down initiatives.

Bottom-up: Strategy by experiment

Strategic experimentation occurs when a company pursues a variety of strategic options in parallel within a given business.3 Some of the strategic options being tested may compete with current strategies or even be contradictory with one another. But they are not random experiments; they are all built around the core competencies of the business and designed to test specific hypotheses about where future opportunities may be found.

At Capital One Financial, a high-performing credit card and financial-services company, for example, executives are constantly starting up small new initiatives, trying out different strategies in the market, seeing what works and what doesn't, shutting down the things that don't work, and "swarming behind" and scaling up the things that do. Thus, at any moment, Capital One is trying out a variety of efforts in the marketplace and testing various hypotheses about corporate strategy. This approach allows the company's strategy to adapt to change constantly. As Capital One's chairman and chief executive officer, Richard Fairbank, has put it, the company's motto is, "Change or die. . . . Rather than wait for the competition to obsolete our products, we do it ourselves."

Top-down: Drive crosscutting themes

Top-down initiatives too can breed creativity. All companies periodically face issues that are bigger than their individual business units. How should the company deal with an economic slowdown in the United States? How should it address growing concern over environmental issues in Europe? How should it respond to new developments in broadband technology?

Yet management can't simply say that these are corporate questions best addressed by the CEO and a few close advisers in a back room. Nor can business units be left to deal, each in its own way, with macro, crosscutting issues, which require the broad engagement of the whole organization and call for new perspectives. Identifying such issues and persuading the organization to deal with them are important ways in which a CEO and senior managers add strategic value to a company. Consider the way GE's leadership devised a significant theme every few years—the push into services and Six Sigma quality improvement, for instance—to shake up the thinking of the company's people and to drive strategic creativity.

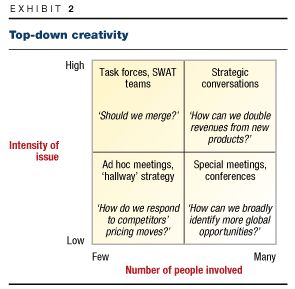

Not every important strategic topic, however, demands a company-wide initiative on the scale of Six Sigma. In our research, we encountered a variety of techniques (Exhibit 2). Some situations require a few people to address a strategic issue—a merger or acquisition, for example—in depth quickly. In these cases, many of the companies in the sample relied on small, elite task forces staffed by top-performing managers temporarily pulled from their normal roles to work on the issues, deliver decisions or recommendations, and disband. Other situations require larger numbers of people to engage in strategic discussions, but not necessarily on a full-time basis. During much of the 1990s at Johnson & Johnson, for example, a process called "FrameworkS" rotated many employees through a continual debate with senior management on important strategic topics that cut across J&J's business units.4 The common ground among the various approaches is that senior corporate leaders identify issues that call for creative thinking and then deliberately disrupt the normal organizational structures in order to encourage focus and new perspectives on these issues.

A job for strategic planners?

Most companies have a senior executive with the word "strategy" in his or her title. How can these executives and their teams help create prepared minds and encourage creative accidents?

While the formal annual planning process must ultimately be owned and driven by the CEO, it is the planning group that should design and run it or, as one executive said, should serve as the "conveners of the conversations." In addition, the strategic-planning group can help identify critical issues for the informal side of planning and assist the senior group in managing top-down initiatives.

Many planning groups also wish to be internal consultants helping the business units analyze strategic issues and undertake special projects. We found that this role can be played successfully, but the groups doing so tend to be small and have very high quality people—typically, rising stars on temporary rotation from the business units rather than permanent staff. This small pool of strategy talent can also be very useful to the CEO and the top team for executing special projects and for preparing for analyst meetings and board presentations.

Many companies can significantly raise their game in strategic planning. Companies should take a fresh look at their annual process and ask whether they are building prepared minds through real dialogue. In addition, companies should think about how they can use both bottom-up experimentation and top-down initiatives to spur strategic creativity. In this way, companies can be better prepared for the real-time job of strategy making, as well as increase the odds that their strategic innovations will shape the world that lies ahead.