The argument for corporate longevity is quite simple: achieving something strategic, significant, and sustainable almost always takes time. Longevity is particularly important for innovation because time and sustained investment are needed to solve really tough problems. To understand why, consider an example from the history of my company, Corning.

This story begins in the mid-1960s. Phone carriers were in trouble because their existing copper lines were being strained by the volume of information. Physicists thought optical technology could provide a solution. There were high-powered lasers, but no way to transport the light without major signal loss.

So Corning stepped up to tackle that challenge. It was a highly speculative project, and Bill Armistead, the company’s chief technical officer at the time, was concerned about taking on such a long-term initiative when he was facing pressure to deliver on existing projects. But he approved the capital expenditure because the challenge seemed uniquely suited to Corning’s capabilities, and he recognized that the technology had enormous potential. Armistead assembled a team of three scientists, and they decided to pursue an unconventional path—using strands of pure silica to transport the light. The lead researcher argued to his colleagues that if you do the same thing everyone else does, the best you can have is a tie.

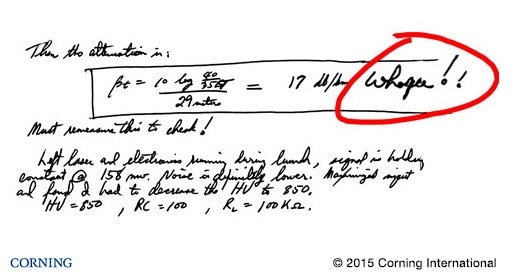

One afternoon in 1970, about four years into the project, one of the scientists was in the lab and decided to run another experiment before leaving for the weekend. He treated a strand of fiber, lined up the laser, examined it under the microscope, and the light hit him right in the pupil. It was literally and figuratively an eye-opening experience.

That was the pivotal moment in the development of optical fiber, as evidenced by the scientist’s highly technical entry—“Whoopee!”—in his lab journal (exhibit). Of course, fiber didn’t proliferate until two decades later, because we needed to develop effective manufacturing processes and the right infrastructure. Today, more than two billion kilometers of optical fiber have been installed worldwide, and a single fiber can transmit the entire collection of the US Library of Congress from Florida to London in less than 25 seconds. This life-changing invention would not have been possible without a long-term focus and sustained investment—a pattern that has repeated itself throughout Corning’s history. We lost money on LCD glass for 14 years before it became an overnight success. Today, that business accounts for about 65 percent of Corning’s profits.

Corning is often questioned on its R&D investments or urged to shed businesses that aren’t delivering double-digit growth in the current year. For example, during the fiber boom in the late 1990s and early 2000s, investors encouraged us to shed most of our business segments and become a telecommunications-focused company because that appeared to offer the most potential for growth. Does anyone recall what happened to the telecom industry in 2002? As someone who watched his company’s net income drop by 70 percent, I sure do. Fortunately, we didn’t follow this advice. We maintained our diverse businesses and our investment in R&D, which not only drove Corning’s next growth surge but also led to breakthrough innovations in LCD glass, fiber to the home, clean-air technologies, and more. I am not saying that we can neglect our responsibility to create value for investors, but we must recognize that the greatest value often comes from our longer-term bets.

I’m a capitalist. I believe capitalism is the best tool to allocate resources and drive progress efficiently. But we can continue to evolve and improve that tool to create more paths to success. The metrics that emphasize near-term results were developed for a world in which capital was scarce; today, we’re awash in capital.

I believe we can create a more balanced approach, between near-term payoffs and long-term investment. As investors, we need to expand our notion of value and broaden our horizon for value creation. As leaders, we need to keep challenging ourselves with questions. What is our unique contribution to the world? How can we be the best in the world at what we do? How do we focus so that we spend at least as much time managing talent, which is scarce, as we do managing capital, which is plentiful? And how do we continually create better versions of ourselves? As directors and trustees, we must understand and embrace the organization’s mission, hold leaders accountable for executing strategies that advance it, and support them through periods of volatility.

Finally, as individuals, we need to ask what we value. What kind of world do we want? What organizations are creating that world? And what sacrifices do we refuse to make? Otherwise, we could sacrifice valuable institutions and lose our opportunity to tackle challenges that generate the greatest progress and improve our quality of life.