After identifying geopolitical instability as a top risk to global growth for three successive surveys, executives now also cite it most often as a threat to both near- and long-term growth in their own economies. In fact, since we first asked about geopolitical risk, the threat it poses to economic growth has hit record levels in McKinsey’s newest survey on economic conditions.1 This increase also reflects respondents’ growing concern about volatility in the Middle East and North Africa. While they have been mostly bullish about the global economy since December 2013, executives are far less optimistic now. Only 39 percent expect global economic conditions will improve in the next six months, compared with 59 percent in our June survey.

Geopolitical risks and shocks to the global economy

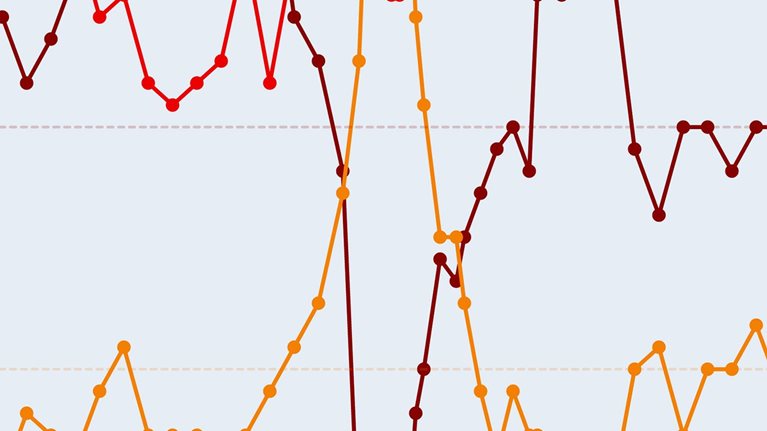

We first began asking executives about geopolitical instability and the global economy in our June 2012 survey. For the past two quarters, they cited it most often as a risk to growth, and a record percentage of executives now do so (Exhibit 1). What’s more, 80 percent of respondents now believe geopolitical instability in the Middle East and North Africa is very likely or extremely likely to shock the global economy in the coming year, the largest share since 74 percent said the same in September 2013.2

Geopolitical instability is more likely than ever to be considered a risk to global growth.

Respondents in North America are the most likely to expect volatility in the Middle East. But greater shares of executives in other parts of the world now agree with this more pessimistic view (Exhibit 2). A year ago, 46 percent of respondents in India said instability in the Middle East was a very or extremely likely shock to the global economy, compared with 83 percent of those in North America. Now, 79 percent of respondents in India expect this instability will upset the world economy.

Across regions, respondents more often expect instability in the Middle East and North Africa than did a year ago.

The domestic threat

With respect to risks to growth in their home countries, executives are nearly twice as likely now as in June and March to cite geopolitical instability. Forty-six percent say so, which is the largest share to identify geopolitics since we first asked in March 2011.

Geopolitical instability is an outsize concern in North America and Europe, particularly outside the eurozone (Exhibit 3). This is not surprising, given the ongoing conflict between Ukraine and Russia and the heightened concern that non-eurozone respondents reported in the past two surveys. Executives in non-eurozone Europe are more concerned than others about instability over the long term, too: 54 percent say geopolitics poses a risk to domestic growth in the next decade, compared with 38 percent of all respondents.

As a risk to domestic growth, geopolitics is of greatest concern to executives in North America and non-eurozone Europe.

In developed Asia, executives maintain a different view of domestic risks. The perceived threat from geopolitics is far less prevalent there; rather, respondents continue to cite low demand most often as a threat to their countries’ growth for the fifth survey in a row. Yet they are notably positive about potential demand (and profits) at their own companies: 58 percent now expect consumer demand for their companies’ products and services to increase in the next six months, up from 35 percent in June and 44 percent in March. Seventy-one percent expect their companies’ profits to increase as well, up from 58 percent in June and 56 percent in March.

Tempered expectations

After nine months of mostly positive sentiments on the progress of the world economy, executives have changed their tune. Now only 37 percent say global conditions have improved in the past six months, down from 56 percent in June—and a much smaller share than the 53 percent who, in March, believed global conditions would improve by now.

Across regions, responses signal that global confidence has most declined in North America and Europe (Exhibit 4). Executives in India remain the most bullish about current conditions, though they’re much less likely than in June to say conditions have improved. In the next six months, executives overall are most likely to expect global conditions will stay the same. Those in emerging markets are more optimistic: half of them predict future global conditions will improve, compared with 39 percent of all respondents.

Executives in North America and Europe are gloomiest on the current state of the global economy.

At the country level, views are more consistent with the results from June: 44 percent of respondents say conditions in their home economies are better now than six months ago, and 48 percent expect conditions will be better six months from now.3 As in June, on the heels of their national elections, respondents in India are the most upbeat: a resounding 95 percent expect conditions there will improve in the next six months (Exhibit 5). At the same time, respondents in other emerging markets are most likely to say conditions at home have worsened. Looking ahead, though, these executives most often expect that domestic conditions will improve in the next six months.

Respondents in India remain the most optimistic about their home economy.

In Europe, executives are almost equally likely to report decline, improvement, or stasis in current conditions, and in their expectations for the future. Responses there also suggest growing concern about unemployment: 34 percent expect their countries’ unemployment rates will increase over the next six months, up from 19 percent who said so in June.