For the introduction to this seven-part series on why and how companies can improve the effectiveness and efficiency of their business and corporate functions, please see “Seven levers for corporate- and business-function success: Introduction”.

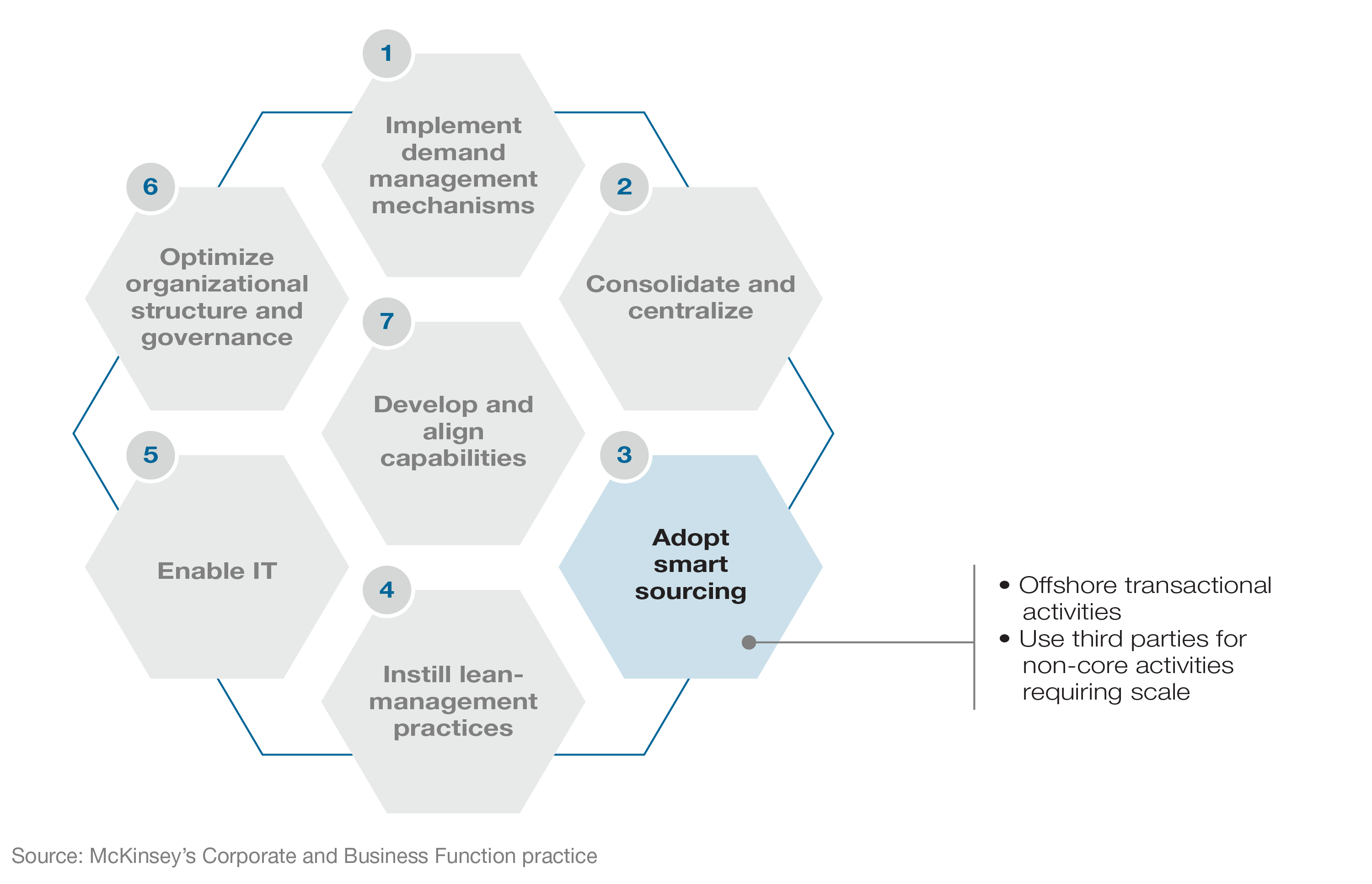

Exhibit

What was once known as “outsourcing and offshoring” (O&O) has become a much more complex matter. As the term implies, organizations once faced two essentially binary decisions: who should own the work (outsourcing), and where the work should be performed (offshoring).

When done correctly, O&O programs resulted in greater flexibility and reduced staffing costs via lower-cost offshore labor. When done the wrong way, the results were often more expensive and less satisfactory than organizations had hoped. As more companies have made outsourcing and offshoring moves, the focus on labor arbitrage and one-time financial gains has diminished, leaving a greater emphasis on the need for quality and responsiveness.

The good news is that hard-won lessons, technology advances, and evolving capabilities (at both vendors and clients) have led to new options that can be calibrated more closely to the individual organization—generating further opportunities for long-term improvement. But taking full advantage of today’s “smart sourcing” requires the organization itself to become smarter. In our recent work across a wide range of industries with businesses reviewing their sourcing options, we have found four capabilities to be especially important.

-

Performance benchmarking. The first question companies must ask may sound obvious, but in fact proves far more difficult to answer than many now assume: “how well are we currently performing in the tasks we are thinking about outsourcing?” The trouble starts when leaders try to estimate what the company now spends to get corporate- and business- function tasks done. With different parts of the organization often following very different procedures for, say, accounts payable, simply finding which employees are responsible may be difficult. One high-tech industrial conglomerate discovered that it was spending twice as much as it thought on revenue management-related finance activities because of hidden pockets of specialists dispersed throughout the organization.

Even more importantly, the company may have no standard performance measures for their corporate and business functions. In these situations, managers negotiating with vendors may focus on cost alone—and not spend sufficient effort outlining the levels of performance that are needed for the business to operate properly. The result is a mismatch between what the business truly needs and the service levels that the outsourcing partner expects to provide. Operational difficulties can ensue if service levels are set too low, or can lead to unnecessary costs if vendors assume services need to be delivered to a higher level than is actually required.

A better approach begins by asking what matters most to the users of a particular business service. For example, in accounts payable, should the finance function focus on optimizing the number of invoices processed per employee, the percentage of invoices that exactly match what was purchased, or the average time each invoice takes? Prioritizing the answers lets the company analyze external benchmarks more carefully in assessing both its own practices and the vendors’ proposals, highlighting trade-offs. If accuracy is the top concern, but benchmarks show that the company’s costs are far higher than vendors would charge, the vendor and company can agree on pricing and service levels that preserve high standards while still providing substantial savings.

-

Structuring and negotiating vendor relationships. The broad outlines of an agreement are only the beginning of an often-intense process in arriving at a final contract. Companies should in particular be sure they understand how to set clear expectations, backed by incentives that create a “win-win” with their partners. In contrast, a contract drafted to lock in very low rates could unintentionally deter the vendor from innovation and new capabilities.

By analyzing a vendor’s economics in detail, companies can find a pricing structure that aligns both parties’ interests. Ideally, the company uses a “clean-sheet” costing approach based on credible benchmarks. This technique is increasingly common among manufacturers in the procurement of both services and tangible components, and can work equally well for corporate and business functions. Starting from scratch, procurement specialists build a realistic cost structure and performance model for the outsourced services, using estimates for all of the various inputs that would contribute to a plausible target price range that could be expected from a vendor. The company’s own practices provide some of the data, especially for basics such as the number of people required at each level of the organization. Outside sources fill in blanks for average labor rates, real-estate values, assumed margins, and so forth.

The picture that emerges allows the company to generate reasonable assumptions and support negotiations that are based on fact rather than optimistic expectations. In reviewing bids for an IT contract, for example, one payments company discovered that the economics for two of the bids would be sustainable only if the scope of the work was much narrower than the company intended. To avoid problems later, the company renegotiated, agreeing to a higher price—but for a scope of work that better reflected its requirements. Conversely, under a similar analysis for a different contract, bids that looked suspiciously low turned out to leave the vendors with decent margins, given labor rates in the vendors’ locations and the level of automation in the vendors’ processes.

-

Managing vendors and service providers. When relationships with external partners sour, a crucial reason is usually a failure of the company and partner to understand each other’s priorities—often the result of a transactional, payment-for-services interaction model. Only by understanding the company’s business goals and culture can the partner collaborate with the company in finding new opportunities for improved operations. Accordingly, from the very beginning companies must educate potential partners and assess their management capabilities to see whether a good fit is possible.

This means, for example, that when evaluating potential partners, a company must get to know more than just the sales team. It needs to meet the personnel who will actually oversee and do the day-to-day work. And the discussions must push beyond basic performance indicators to reach deeper questions, such as how the company and vendor will prioritize issues in solving problems together.

One mining company’s experience in improving the value of an outsourcing arrangement illustrates the potential for building this relationship early on. The company had outsourced several finance-related tasks to a leading business-services vendor. The handover was quick, leaving little time for internal finance staff to work with the partner and explain the company’s business priorities. As a result, there was a significant misalignment between what the company’s finance staff expected and what their partner delivered.

Quality was frequently a problem, generating excessive rework for internal company staff, while the vendor incurred higher-than-expected costs as it tried to fix issues with little guidance on where it was falling short. After two years of frustration on both sides, company executives flew the partner’s account manager in to spend time with the internal finance staff so that he could see what they were trying to do with the data that was being generated. By jointly working through the issues, the account manager and internal finance team were able to identify and immediately implement a number of improvements that eliminated the quality problems within weeks, at negligible cost. Adhering to a collaborative review process further strengthened the relationship and enabled several additional improvements in subsequent years.

-

Developing local market knowledge. While local market knowledge is important to all companies considering their sourcing alternatives, for companies considering a captive center, it is essential. Factors that are of comparatively low importance in advanced economies, such as the reliability of local utility and transport networks, loom large in many markets with attractive labor pools. And labor costs themselves are rising quickly, especially in well-known places such as China, for research, and India, for IT application development.

Organizations that are new arrivals in a market will find themselves competing not only with highly-regarded local employers, such as India’s software leaders or China’s government labs, but also with other foreign companies that staked a claim earlier and built their brands. Latecomers will either have to pay somewhat more, or accept less-skilled talent. And in either case, attrition will likely be high, with employees quickly moving on to better-known options while the company finds its footing—a process that itself will take longer as the company bridges cultural gaps and establishes effective performance and incentive plans.

Only by factoring in these constraints can a company make a realistic choice. Captive centers may remain a viable option, but only for those organizations that truly have the brand and the local market reputation to compete effectively.

Organizations that build all four capabilities see a significant advantage in building effective corporate and business functions. The high-tech industrial conglomerate, for example, overinvested in its partner relationship from the beginning by having its senior finance managers spend significant time at the vendor’s headquarters and delivery centers. These steps allowed the company to take much better advantage of the vendor’s low-cost delivery-center locations and technical know-how—resulting in a 50 percent reduction in costs, while improving the consistency of information recorded in its financial systems and reducing the time needed to close its books at month end.

Dash Bibhudatta is an expert in McKinsey’s Chicago office, Jonathan Silver is a principal in the New York office, and Edward Woodcock is a senior expert in the Stamford office.