The health status of Africans remains far worse than that of people in many other developing regions, to say nothing of Europe and North America. Although a lack of access to health care and serious health system deficiencies are important reasons for this phenomenon, other elements aggravate it. One is insufficient research and development aimed at addressing Africa’s unmet health needs. The result is a lack of efficient therapies for many illnesses that affect that continent almost exclusively and are therefore beyond the scope of most research efforts in the developed world. Consequently, improving the health of Africans implies not only addressing the deficiencies of access and health systems but also stimulating the development of suitable drugs and diagnostics.

A look at the relationship between GDP per capita and life expectancies illustrates the magnitude of the problem. While the GDP of Africa as a whole has grown by over 200 percent in the past 20 years, only two extra years of life expectancy were added during that time. Asian countries with comparable GDPs per capita tend to have life expectancies 5 to 10 years higher than those of their African counterparts. Even high-GDP African countries, boasting per capita figures comparable to those of many countries in Eastern Europe and South America, have life expectancies 10 to 20 years lower than those of comparable nations in the other continents. Undoubtedly, Africa’s weak health systems and HIV/AIDS epidemic are contributing to the problem. Yet several countries elsewhere, such as Jamaica and Thailand, with similarly weak systems or similarly burdensome HIV/AIDS rates, still have life expectancies that are 5 to 25 years longer.

A big part of the problem is a lack of tools to diagnose and treat the diseases of Africa. Some available drugs addressing those that affect it disproportionately are not fully effective and present high toxicity levels. Acquired resistance has made other therapies less effective.1 Low levels of patient compliance because of the duration and complexity of certain treatments is another impediment. What’s more, diagnostic tools for some common diseases in Africa are hard or impossible to apply in the field or could be made more broadly usable in difficult environments. While emerging public–private partnerships between international organizations and pharmaceutical companies are making inroads, these efforts are still few and far between. In fact, only about 1 percent of new drugs developed from 1975 to 2004 treat diseases of the poor, although such diseases account for more than one-tenth of the global burden.2

Current R&D efforts aimed at treating African diseases mostly depend on organizations outside Africa. They try to find solutions for its pressing health needs but not to create a sustainable R&D structure on the African continent. To develop a plan for a pan-African health R&D project, McKinsey analyzed five years of health research output and scientific networks involving African scientists. As highlighted in other recent publications,3 we conclude that a system governed by Africans in Africa is needed to provide a sustainable funding mechanism that would encourage African scientists to collaborate on common health concerns, share expertise, and build capacity.

The challenges ahead

The argument for increased R&D to develop drugs and diagnostics for diseases that disproportionately affect Africa is compelling. Although promising trends are fostering the development of such an R&D capacity, the African countries responsible for the largest number of biomedical-research publications—such as Egypt, Nigeria, and South Africa—generate 15 to 150 times fewer research articles than leading developed countries do. More alarmingly, they generate 1.2 to 8.0 times fewer research publications than other developing countries, such as Argentina, Brazil, India, and Thailand. These figures indicate that while research to treat predominantly African diseases and conditions is being conducted, major challenges still prevent these efforts from reaching sufficient scale and productivity.

A significant knowledge gap

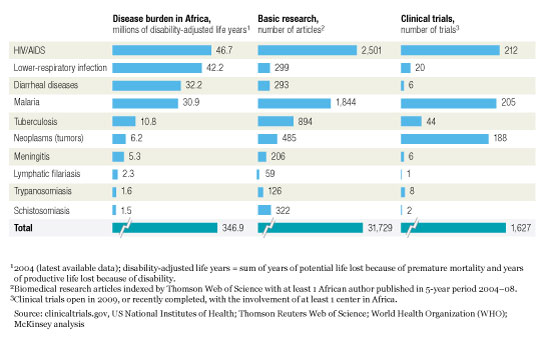

Many diseases with a high prevalence in Africa are either almost exclusive to it (for example, onchocerciasis, human African trypanosomiasis, schistosomiasis, and malaria) or disproportionately affect the continent (HIV/AIDS, ascariasis, meningitis, trachoma, lower-respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, leishmaniasis, tuberculosis, and lymphatic filariasis). World Health Organization (WHO) estimates indicate that this group of diseases accounts for more than 50 percent of Africa’s total disease burden. Accurately quantifing their economic impact is difficult, but rough estimates show that they reduce the continent’s GDP by as much as 20 percent, or $200 billion, a year.

Despite the terrible impact these diseases have on Africa’s economic development and welfare, they have been seriously underresearched: with the exception of HIV/AIDS and malaria, the pipeline of products aimed at treating them is just about empty (exhibit). Their almost exclusively African incidence means that interest from the international research community is low, which emphasizes the need for drugs and diagnostic R&D efforts owned by Africans.

Research is lacking

A favorable trend is emerging, though. An analysis of five years of biomedical-research articles originating in Africa shows that the number of articles on different diseases correlates well with their incidence in Africa.

A low degree of collaboration

The productivity of R&D efforts, both public and private, is maximized by harnessing the synergies generated by networks of scientists with complementary skills and capabilities. These collaborative networks also benefit when expertise is transferred from one network member to another, which builds capabilities and increases a network’s capacity. In academic environments, the availability of funds drives the creation and work of collaborative networks, so African scientists strongly tend to collaborate not with one another but with scientists in Europe and the United States, where research funding and technology are more readily accessible. In fact, only 10 percent or less of the funding of R&D at many public-health research centers in Africa is local; the rest comes mostly from the United States and Europe, either directly or through collaborations.

Our analysis of Africa’s research output in 17 selected disease and functional areas shows the low degree of collaboration within the continent, despite the substantial number of centers publishing in collaboration. For malaria, a total of 1,844 research articles from 2004 to 2008 had at least one African author. Of these articles, over 40 percent had a lead author from Africa and most were published collaboratively. Despite the importance of malaria in many African countries, however, only 13 percent of these articles involved collaboration between authors in more than one African country.

A more exhaustive analysis of all the African biomedical-research output from 2004 to 2008 (31,729 articles involving 20,714 institutions) confirmed the trend. More than 92 percent of the institutions collaborating with the 20 most productive and collaborative institutions in Africa are either from the same country or from outside Africa. In fact, while most publications result from collaboration, in only 5 percent of all cases does it involve scientists in more than one African country. Notably, only 5 percent of the patents granted to African inventors result from collaboration between inventors in more than one such country.

The interactive exhibit below shows the most productive and collaborative institutions publishing in HIV/AIDS and malaria networks, respectively, with the involvement of at least one African scientist. The links between these institutions were traced (through coauthorship), and the circles marking their locations were sized according to the number of articles led by an author from a given location. While there are some links between African institutions, suggesting a certain degree of local collaboration, the exhibits show that collaboration is clearly biased toward Europe and the United States. Although HIV/AIDS is an area of great interest for both developed and African countries, diseases that mostly affect Africa, such as malaria, show the same pattern. That bias represents a major challenge because it has the effect of fostering the misalignment between medical research and Africa’s health priorities and prevents Africans from driving the research agenda.

Despite the low degree of collaboration within Africa, several countries there have a pool of human capital and a number of research centers that could collectively form strong R&D networks. A few established African research centers have a wide range of expertise: they participate in efforts that, although linked to the developed world, generate significant numbers of research articles. These centers are also true originators of research and central elements of global collaborative efforts. The existence of such high-quality, productive, and connected institutions in Africa indicates that active R&D networks could and should be formed there and eventually carried to scale.

Insufficient investment and ownership of R&D

Lifting the health status of whole populations involves concerted efforts by governments and other local stakeholders, including the private sector, the research community, and influential individuals. As long as the bulk of R&D investment comes primarily from foreign sources, alignment between local R&D efforts and local priorities will remain difficult to achieve—a situation that demands attention from African governments but, by and large, hasn’t received it.

Africa as a whole lags behind the world’s other developing regions, such as South America and Southeast Asia, in overall R&D spending per capita. Moreover, great disparities exist among subregions in Africa itself. While the southern region invests, on average, more than the world median in R&D, western and central Africa present a grim picture when compared with other parts of the developing world and the rest of Africa. This intra-African inequality magnifies the funding-gap challenge.

The need to increase R&D expenditures for health is well recognized. The African Union has set a target: dedicating the equivalent of 2 percent of total health care spending to health research by 2015—0.1 percent of GDP and 33 percent of overall R&D. Kenya now spends 0.15 percent of GDP on health research, so 0.1 percent is a plausible target. In fact, some African countries are aggressively increasing their total R&D expenditures. South Africa, for example, will soon be devoting 1 percent of its GDP to R&D. Egypt will spend 0.6 percent of GDP on R&D by the end of 2010 and hopes to reach 1 percent by 2017.

Ownership of the R&D process is a concern as well, not only because funding is now primarily external, but also because Africans are seriously underrepresented in organizations devoted to Africa’s health problems. Only 9 to 14 percent of the board members of international organizations focused on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, for example, are Africans.4 Although these organizations have been very successful, local ownership of the research agenda is necessary to meet current and future local health needs sustainably.

Building innovative networks

The solutions to these issues lie within Africa. Their paramount objective is to develop a self-sufficient, pan-African R&D system that could address not only today’s problems but also evolving public-health issues. The key is to harness the untapped power of collaboration among African researchers by forming and supporting networks of research groups in Africa. This model, recently endorsed by the African research community,5 would turn laboratories that complement each other technically and functionally into cohesive networks engaging in projects specifically aimed at developing new tools to address African diseases.

This approach would promote African research agendas and local ownership, since such networks would be formed by investigators working in Africa and cooperating to advance their own local scientific interests. Financial support for these networks would also develop the capabilities of local scientists and improve Africa’s health R&D infrastructure.

To ensure that drugs and diagnostics advance along R&D pipelines, the proposed network-based model should adhere to these principles:

Strong project-management coordination for each network to ensure timely progress. A broad view of these networks’ project portfolios will be needed to prevent duplication and ensure that synergies are captured.

Significant project funding through five-year renewable grants, which would change the culture of short-term research grants now widespread in Africa. Such funding cannot be provided though typical yearly donor campaigns. It will require a sustainable, proven solution, such as the establishment of an independent, professionally managed endowment fund.

Additional grants to upgrade the facilities and equipment needed to improve the way a project network functions.

Better intellectual-property management that responds to the needs of inventors and the African public, perhaps through pan-African technology-transfer offices analogous to those of major research universities.

Increased ownership by key stakeholders in Africa, as well as efforts by public and private organizations to guarantee that the drugs and diagnostics these networks develop will move into production.

First, the approach outlined above focuses on bringing Africa’s researchers together into regional networks to harness the capacity and capabilities now existing on the continent. Second, it involves local stakeholders, improving the chances that specific initiatives will be aligned with African health priorities. Finally, it aims to create a sustainable stream of projects that could develop new health tools.

Successful implementation will require a concerted, Africa-led and -based effort supported by the international community. The model aims to avoid competition between the new research networks and existing players, to create partnerships that would prevent the duplication of effort, and to make products easier to develop and access.