Whatever role low interest rates and high government spending may have played in helping economies to stabilize during the recent global recession, they now have companies, investors, and policy makers alike on the lookout for inflation to come roaring back. Some economists are already warning of a return to the levels of the 1970s, when inflation in the developed countries of Europe and North America hovered at around 10 percent. That’s not uncommon in Latin America and Asia, where emerging economies have seen double-digit inflation for many years.

At first glance, the effects of inflation on a company’s ability to create value might seem negligible. After all, as long as managers can pass increased costs on to the customer, they can keep inflation from eroding shareholder value. Most managers believe that to achieve this goal, they need only ensure that earnings grow at the rate of inflation.

Yet a closer analysis reveals that to fend off inflation’s value-destroying effects, earnings must grow much faster than inflation—a target that companies typically don’t hit, as history shows. In the mid-1970s to the 1980s, for instance, US companies managed to increase their earnings per share at a rate roughly equal to that of inflation, around 10 percent. But to preserve shareholder value, our analysis finds, they would actually have had to increase their earnings growth by around 20 percent. This shortfall was one of the main reasons for poor stock market returns in those years.

Not just a rising tide

Inflation makes it harder to create value for several reasons, especially when its annual growth rate exceeds long-term average levels—2 to 3 percent—and becomes unpredictable for managers and investors. When that happens, it can push up the cost of capital in real terms1 and lead to losses on net asset positions that are fixed in nominal terms. But inflation’s biggest threat to shareholder value lies in the inability of most companies to pass on cost increases to their customers fully without losing sales volumes. When they don’t pass on all of their rising costs, they fail to maintain their cash flows in real terms.

To illustrate the point, let’s examine the case of a hypothetical company that generates steady sales of $1,000 a year, with earnings before interest, taxes, and amortization (EBITA) of $100 and invested capital of $1,000. If the cost of capital is 8 percent, the company’s discounted-cash-flow (DCF) value at the start of year two—or any year—equals $1,250.2

Now assume that inflation suddenly increases from zero to 15 percent in year two and stays at that level in perpetuity and that costs and capital expenditures are affected equally. Also assume that the company can increase its earnings at the rate of inflation and maintain its 10 percent sales margin by increasing prices for its products while keeping sales volumes and physical production capacity constant. In the process, it will lift its returns on capital to almost 20 percent after 15 years.

This level of performance may seem impressive or at least adequate—yet not all is as it seems. The growth of free cash flows would be negative in the first 5 years and only gradually rise to the rate of inflation, in year 17.3 That, combined with an increase in the cost of capital, to 24 percent,4 pushes down the company’s value to as little as $481.5 To fully pass on inflation to customers without any loss of sales volumes, the company would need to raise its cash flows at the rate of inflation—not its earnings, as many practitioners surmise (see interactive).

But if all cash flows grow with inflation, the implication is that the company’s reported financial performance increases sharply. In year 2, earnings growth would have to exceed 33 percent; sales margins would have to increase to 11.6 percent, from 10.0 percent; and returns on invested capital (ROIC) to 13.4 percent, from 10.0. After 15 years of constant inflation, margins and ROIC would end up at 17.6 percent and 34.7 percent, respectively. The company’s ROIC must rise that far to keep up with inflation and the higher cost of capital.

The reason is that invested capital and depreciation, instead of tracking inflation precisely, are usually delayed. In year 2, for example, annual capital expenditures increase by 15 percent, but this adds only negligibly to invested capital. Annual depreciation also changes in year 36 by only a small amount. And because in each year just 1/15th of the company’s assets are replaced at inflated prices, it takes 15 years of constantly rising prices to reach a steady state where capital and deprecation grow at the rate of inflation. All the while, sales margins and ROIC increase each year until the company reaches the steady state in year 17.

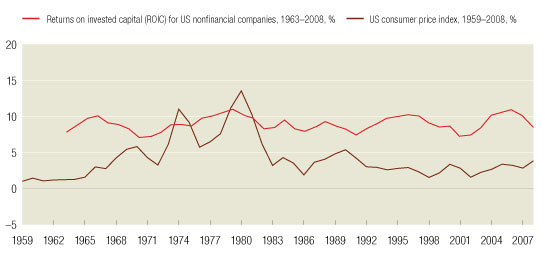

Although this example is stylized, the conclusion applies to all companies: after each acceleration in inflation, reported earnings should be expected to outpace inflation, and reported sales margins and returns on capital to increase, even though in real terms nothing has changed. Unfortunately, history shows that in periods of rising inflation, companies do not achieve big improvements in reported returns on capital. Those returns have been remarkably stable, at around 8 to 11 percent, in the United States—even during the 1970s and early 1980s, when inflation hit 10 percent or more (exhibit). If companies had been successful in passing on inflation’s effects, they would have had returns of around 25 to 30 percent in those years. Instead, they barely managed to keep returns at pre-inflation levels.

A history lesson

The perils of falling behind

One likely reason companies destroy value is that they can’t pass cost increases on to customers—or can do so only with a time lag. This problem is especially costly when inflation is high and unpredictable: a half-year delay in passing on 15 percent inflation implies that revenues are always 7.5 percent too low, causing margins to plummet. Another reason could be that managers facing inflation don’t sufficiently adjust their targets for the growth of earnings and sales margins. Keeping margins and returns on capital constant in times of inflation means that cash flows and value are eroding in real terms. EBIT7 growth in line with inflation is also insufficient for sustaining a company’s value. This is even truer for leveraged indicators, such as earnings per share.

Whatever the exact reason may be, history shows that companies do not manage to pass on inflation fully, so their cash flows decline in real terms. In addition, there is empirical evidence that in times of inflation, investors increase the cost of capital in real terms. Lower cash flows and a higher cost of capital are a proven recipe for lower share prices, just as we saw in the 1970s and 1980s.