Executives around the world are working longer hours, taking on additional responsibilities, and experiencing higher levels of stress as they struggle to address the economic downturn, according to a McKinsey Quarterly survey.1 What’s more surprising, rather than feeling as turbulent as the economy, executives say they feel relatively stable and content about their companies, their work, and their performance as business leaders since the crisis began. All is not well, though. Beyond the averages—and the executive suites—middle managers report dramatically lower levels of contentment than their more senior colleagues do, as well as less of a desire to stay with their current employers.

In this survey, a range of executives—from corporate directors and CEOs to middle managers—were asked if and in what way the crisis has led to changes in their professional roles and the ways in which they spend their time on and off the job. They also responded to questions about their levels of physical and mental stress and its sources, rated their own performance as business leaders and the performance of their superiors, and identified the capabilities and mind-sets they have found helpful for tackling the new economic conditions.

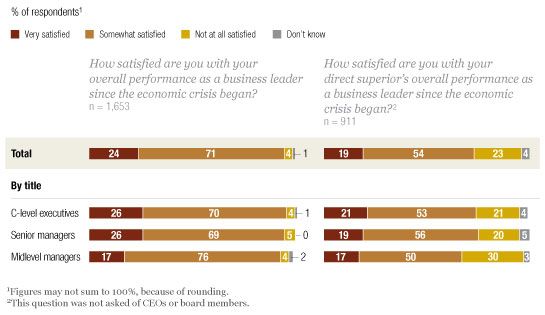

Most respondents are working more hours since the crisis began, and nearly 40 percent have more responsibilities without the benefit of a new title. But although stress levels have increased, most executives say they can cope. Further, most find their work more exciting and meaningful than they did before the crisis, and almost all—95 percent—are at least somewhat satisfied with their own performance as business leaders. Far fewer are impressed with the work of their direct superiors. As for middle managers, compared with more senior colleagues, they are less committed to staying with their companies, less enthusiastic about their work, less satisfied with their own performance, and far less satisfied than more senior executives with how their bosses are doing.

Quantity and quality of work

More than 80 percent of executives say their organizations’ financial performance has suffered as a result of the crisis. Not surprising, just as many say their companies have already taken steps to reduce operating costs, or plan to do so in 2009, and almost half note efforts to reduce capital investments and increase productivity.2 Executives are working harder in this environment—55 hours a week on average, compared with 45 before the crisis. Two out of three are spending more time than before on directly monitoring or managing operating performance and cash flow. And just over half say they are putting extra hours into setting strategy and motivating employees; four out of ten into dealing with immediate and unforeseen problems and engaging with customers, suppliers, and other external stakeholders.

Though monitoring financial performance is crucial in a crisis, the findings suggest that executives should place a higher priority on motivating employees than they are now. More than half of the executives who are very or somewhat satisfied with their own overall performance as business leaders say they are spending extra time on motivating people—compared with some 30 percent of those who aren’t at all satisfied with their own overall performance.

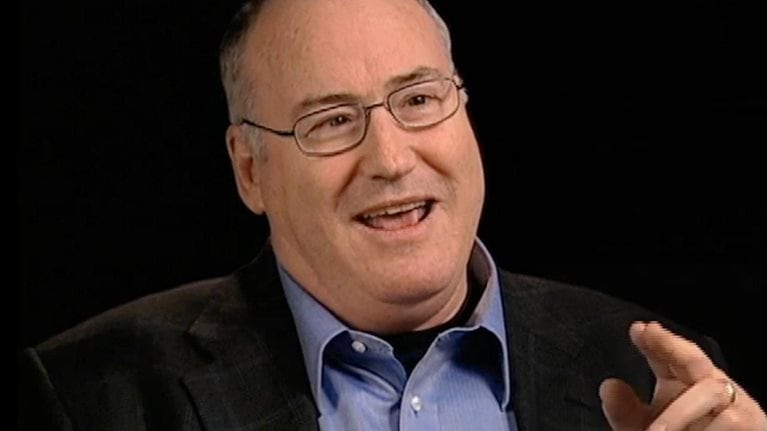

Even executives who are taking more time to motivate their people aren’t always taking the steps that, in our experience, are most effective. They most often motivate by talking about their companies’ values or direction and their financial performance; far fewer express interest in their employees’ lives outside of work or otherwise try to make individual connections with employees (Exhibit 1). A focus on the big picture, we have seen, can be insufficient for motivating middle managers and others when they are grappling with new responsibilities and downsizing programs in an atmosphere of great uncertainty.

The wrong kind of talk

Prepared with people skills

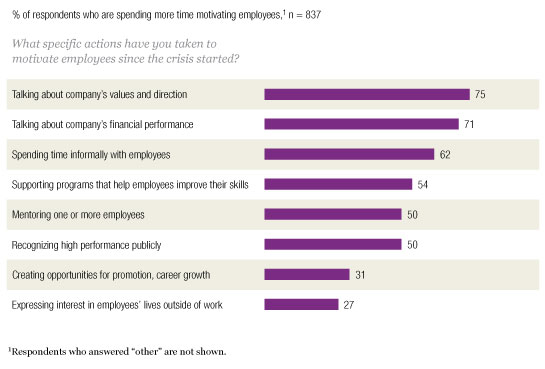

A minority of executives—44 percent of C-level executives, 39 percent of senior managers, and 30 percent of middle managers—say they were well prepared to deal with the crisis. Notably, when respondents were asked what capabilities and mind-sets had helped them to prepare, middle managers were less likely than senior managers to indicate that any mind-set or capability had prepared them. (Exhibit 2).

How, if at all, do capabilities and mind-sets correlate with executives’ satisfaction with their own overall performance? An interesting picture emerges when we compare the selection of capabilities with levels of satisfaction. The ability to deal with uncertainty, a realistic outlook, and the ability to make tough decisions are selected by similar numbers of executives regardless of whether they are very, somewhat, or not at all satisfied with their own performance. In effect, these capabilities or mind-sets may be necessary for satisfaction but they do not seem to be distinguishing. Instead, people skills—good relationships with employees, peers, and external stakeholders, as well as the ability to inspire and align a team—come to the fore. Executives who are very satisfied with their performance as business leaders are far more likely to select these capabilities as those who aren’t at all satisfied.

Crisis-preparedness

Outperforming the boss?

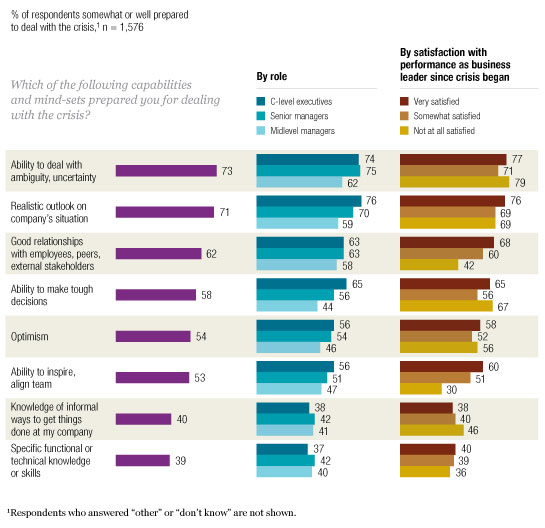

Executives overall are most satisfied with their own performance in providing strategic insight (Exhibit 3). Far fewer executives are pleased with themselves when it comes to positioning their businesses for growth, retaining and attracting talent, or developing leaders—areas that are important for their companies’ chances to thrive after the crisis.

What’s gone well

Satisfaction levels are markedly lower when executives rate their overall performance (Exhibit 4). Just 26 percent of C-level and senior executives and 17 percent of middle managers are very satisfied with their own overall performance. Across all three groups of executives, an overwhelming majority are somewhat satisfied. Further, satisfaction levels drop even more dramatically when respondents rate the performance of their bosses. Twenty percent of C-level and senior executives and 30 percent of middle managers aren’t at all satisfied with their superiors’ performance—another indication of middle managers’ overall lack of connection to their current companies.

Weaker overall

Middle managers get hit

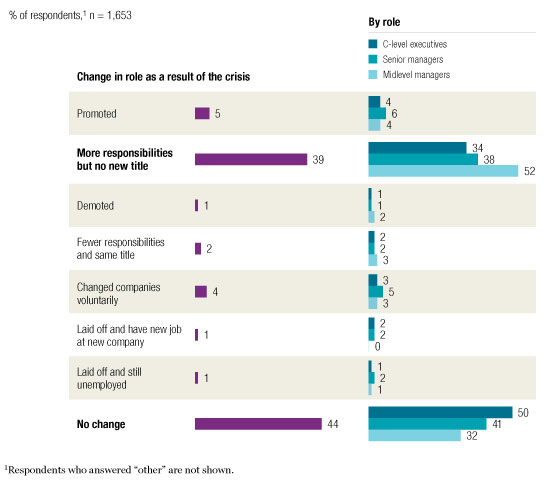

Efforts to reduce costs, including staff cuts, have increased the responsibilities shouldered by many executives but, not surprisingly, have resulted in few promotions (Exhibit 5). Among middle managers, more than half say they have taken on additional responsibilities.

This change, along with most companies’ relatively low priority on motivating individuals and the other differences in perceptions between middle and higher-level managers, may help to explain these managers’ relatively greater disconnection from their companies. Indeed, 27 percent of middle managers (compared with 18 percent of all executives) say they find their current roles less meaningful and exciting than their roles before the crisis. And just 36 percent of middle managers (compared with 52 percent of all executives) report that they are very or extremely likely to choose to be with their current employers two years from now, given their current excitement about their roles and their companies as well as their current stress levels.

Despite this dissonance, it is notable that around 80 percent of all the executives we surveyed find their current roles to be equally or more meaningful than before the crisis and are at least somewhat likely to stay with their employers.

More responsibility, fewer promotions

Stress? What stress?

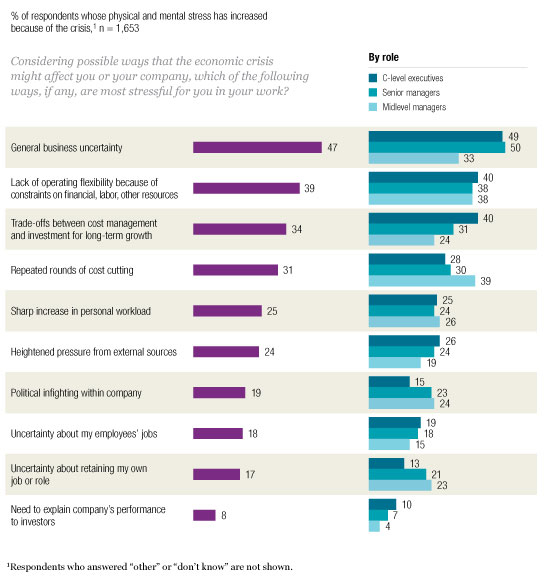

Most executives are coping fairly well with the potentially stressful effects of the crisis. Almost 20 percent say their levels of physical and mental stress have not changed at all, and more than 50 percent say stress levels have increased but are manageable in the long term. However, one in five executives say they are worried going forward about coping with the increased stress levels.

Among the middle managers, just over one in four are worried about coping. These managers also differ from senior executives in the sources of stress they identify (Exhibit 6), though overall, executives at all levels are mostly preoccupied with their companies’ situations rather than their personal circumstances.

In addition, some sources of stress are likelier than others to be important for executives who aren’t satisfied with their performance during the crisis: a lack of operating flexibility, repeated rounds of cost cutting, uncertainty about one’s job, and explaining the company’s performance to investors.

Personal concerns on the back burner

Longer work hours are taking a toll on the time executives devote to off-work activities, which may also be detrimental to their effectiveness as business leaders. Those who are finding the time to recharge outside of work are more satisfied with their work performance: although there is little difference in the amount of hours executives at all satisfaction levels are working, 65 percent of the executives who are not at all satisfied with their own overall performance as business leaders are participating less frequently than before in social, religious, athletic, or other activities that interest them, compared with 48 percent of those who are somewhat satisfied and only 36 percent of those who are very satisfied with their professional performance.

Looking ahead

-

Middle managers have been hit particularly hard by the demands and effects of the crisis. Companies may therefore need to complement their focus on cost cuts and productivity improvements with increased efforts to motivate the managers who are implementing these steps and are critical to the long-term success of their businesses. Making personal connections and helping managers find meaning in their work, our experience shows, will be especially important.

-

Many executives have found it difficult to look beyond addressing the short-term effects of the crisis. But they themselves indicate they can do better at positioning their businesses for growth, retaining and attracting talent, and developing leaders. Carving time out of operating routines to address these issues will be a key to recovery.

-

The survey findings show that executives who neglect off-work activities important to them are less happy with their performance as business leaders. Executives would do well to keep this in mind as they grapple with their competing priorities.